|

Raymond

P. Kenny |

|

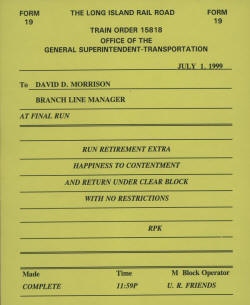

The Long Island Rail Road sign that hung on the back wall above the LIRR employees, in the NY Penn Station ticket office, was removed during the recent remodeling of Penn and donated to the RMLI. Now on permanent exhibit at RMLI-Riverhead placed currently above the exhibit celebrating the life of past President, Vice President and LIRR Employee, Ray Kenny. Photo/Archive: RMLI-Don Fisher |

|

|

|

|

Former

acting LIRR President Raymond Kenny dies at 68 NEWSDAY Former

acting LIRR President Raymond Kenny dies at 68 NEWSDAY____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Raymond Kenny retired in 2014 after working more then 40 years at the Long Island Rail Road. By Alfonso A. Castillo Updated April 18, 2020 10:19 PM Former acting LIRR president Raymond Kenny, a Lindenhurst resident whose childhood fascination with trains led to a railroading career that spanned a half-century, died Saturday from complications of COVID-19, his family said. Kenny's family said he was admitted to Good Samaritan Hospital Medical Center about a week ago with symptoms of the coronavirus, later tested positive and was put on a ventilator. Kenny, who most recently headed rail operations for New Jersey Transit, was 68. In a 2014 interview, Kenny said he became interested in the LIRR while riding the train between his Cedarhurst home and Molloy High School in Queens. He began working at the railroad as a summer ticket clerk in the early 1970s, while pursuing a bachelor's degree in business administration from John Jay College. After graduating, he was hired full time on the management side of the LIRR as a junior industrial engineer. Kenny worked in various management roles until being promoted in the early 2000s to chief transportation officer. When then-LIRR president James Dermody retired in 2006, Kenny served as acting president for 10 months. In the role, Kenny was charged with leading the railroad’s response to the concerns raised by a Newsday investigation about the dangers of wide gaps between trains and station platforms. "I was not stressed, because I had a lot of help. Everybody was pulling the same weight," Kenny said in 2014 about his time as acting president. "I really did enjoy the job. I tried to bring the place together." After Helena Williams was appointed as the railroad’s 38th president, Kenny took on the position of senior vice president of operations. Williams, who is now a deputy county executive in Nassau, acknowledged leaning heavily on Kenny’s experience and wisdom as her “right hand man.” “He was always methodical in evaluating every situation. And he always stressed the most important issue for everyone on the railroad was situational awareness, because he wanted to always protect the well-being of the employees,” said Williams, who credited Kenny with coming up with key strategies for the LIRR’s Double Track project between Farmingdale and Ronkonkoma and for its East Side Access link to Grand Central Terminal. “It was his passion. His life.” After serving as a “champion” in the railroad’s recovery from super storm Sandy, according to Williams, Kenny retired from the LIRR in 2014. He worked in the private sector until being hired by NJ Transit in January 2019 as senior vice president and general manager of rail operations. Kenny held three master’s degrees and was working toward a doctorate in emergency management, his brother Ed Kenny said. “He was a tremendous leader. He loved the work that he did,” said Ed Kenny of Lindenhurst, who also remembered his brother as “a wonderful family member, a great big brother and an uncle.” Industry leaders on Saturday remembered Kenny as a railroading giant. Anthony Simon, general chairman of the International Association of Sheet Metal, Air, Rail and Transportation Workers, the LIRR's largest union, called him a “true railroader who worked his way through the ranks and became a legend in the railroad industry.” Kevin Sexton, general chairman of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen Division 269, which represents LIRR train operators, said Kenny's "knowledge and commitment to this industry were second to none." Christopher Natale, of the Brotherhood of Railroad Signalmen, called Kenny a "beloved, gentle soul." Kevin Corbett, NJ Transit president and CEO, said, "Ray's reputation and experience in the industry are unparalleled." "While I never had the opportunity to work with him at the LIRR, the results of his leadership were clear throughout the railroad when I came on board," current LIRR president Phillip Eng said. "The entire railroad is hurting right now." Kenny is also survived by another brother, Bob, also of Lindenhurst. A private wake for family members is scheduled for Wednesday at the Lindenhurst Funeral Home, followed by a public motorcade at noon from Our Lady of Perpetual Help Roman Catholic Church to Pinelawn Cemetery, where he will be buried. |

|

|

|

|

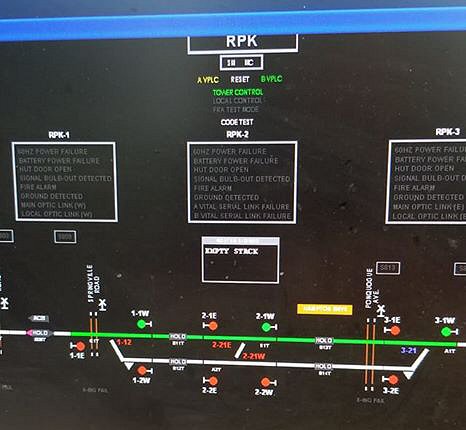

"RPK

1", "RPK 2", "RPK 3" INTERLOCKING FORMERLY "ND" BLOCK LIMIT SIGNAL

HAMPTON BAYS. AUTOMATIC INTERLOCKING R.C. FROM "BABYLON" IN SVC: 11/13/17

PER G.O. #303. RENAMED IN HONOR OF RAYMOND P. KENNY WHO HAD A 44-YEAR CAREER

ON THE LIRR STARTING AS AN RPK1-3 remote controlled interlocking at Babylon. Photo/Archive: Christopher Soundy |

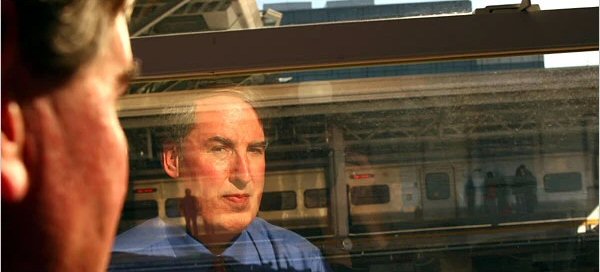

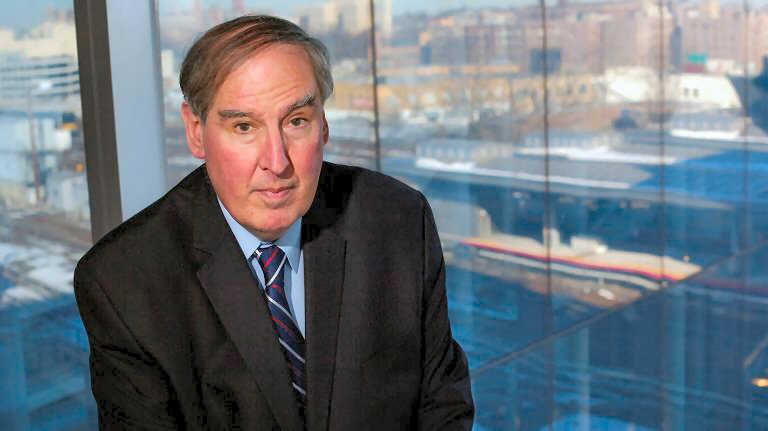

Raymond P. Kenny 2014 Photo: Uli Seit - NEWSDAY |

Ray

Kenny served a 40-year career with MTA-Long Island Rail Road (LIRR). He most

recently served as Senior Vice President – Transportation and Facilities

Planning, responsible for MTA Capital Construction’s efforts on the East

Side Access project. In the mid 2000's he

Ray

Kenny served a 40-year career with MTA-Long Island Rail Road (LIRR). He most

recently served as Senior Vice President – Transportation and Facilities

Planning, responsible for MTA Capital Construction’s efforts on the East

Side Access project. In the mid 2000's he