|

St. Maarten PLAYER DEVELOPMENT

- TRAINS |

||||

|

Our logo is a train engine.

The little ones start out reading Thomas the Tank engine. When they finish a book, they get to play with one of the four trains sets we have. Set one is a wooden Thomas that can be pushed around the track but also has a battery. As the reading level improves so does the quality and size of the train set. Set two is just an oval with a hand car with two railroaders pumping away to get to work. Set three is a double track O gauge set. We model the Long Island railroad passenger service but can sneak in a freight train if we pretend it is evening time. The last set is HO. There we have both steam engines and some diesel power. From the beginning, trains played a big part in encouraging the children to work. Originally, we thought of Thomas as our logo, but it is copyrighted. We did some research and found the GG1. A unique engine. Streamlined, first without rivets, and electric. Best of all it was a double ender so could change direction easily. The story we found said the engineers were working on building submarines. They were worried that after the war they would be out of a job, so they designed the GG1 in 1939. The war would not end till 1945. Now that is some advanced planning. Thus, we decided the GG1 should be our logo. We also had a suggestion of a baseball with crossed bat and pencil. You guessed it, the train won easily. We are fortunate that tourist have become friends and help us. Conductor Steve, yes a real conductor on the LIRR has taught the children all about ticket punching, making announcements and some safety rules on trains. Now when the children play trains, they have a dispatcher who uses a walkie-talkie to tell the engineer when he can proceed to the next stop. Then the conductor makes the announcement, closes the car doors and off they go. He is also the webmaster for the Oyster Bay Railroad Museum Facebook page. He lets the children write train stories and he posts one a week. The stories have to be well researched and about the Long Island Rail Road. We have Big Roger a modeler from Pennsylvania. He brings kits to the island and shows the children how to assemble them. He taught the children they could name their own railroad and helped design the P & D Railroad Logo and came up with the slogan Home of the Great Salt Pond Route. Mr. Don from Canada use to be in the railroad maintenance equipment production. He has visited several times and talked with the children about speeders and high rail trucks. Those are tracks that have both metal train wheels and rubber wheels. Using hydraulics to raise and lower the wheels the truck can drive on the road or the tracks. Forklift Gary is a volunteer at the Oyster Bay Railroad Museum. He drives the forklift to help set up outside displays. He sends us videos on the equipment there and how it was used. The children have raised more than $6,000 to help restore the museum's steam engine 35. Pilot John was a U.S. Navy pilot who landed on aircraft carriers.

He was also a manager of a race car team. He does not know a lot

about trains, but he reads a lot of magazines and sends us cool

stories about trains. More recently we have met Steven Lynch of Trains are fun website.

We found the site by doing research on the LIRR. Now we have become

friends. He has put up this Player Development Web Page and asked the

children to write stories to fill it. |

||||

|

Player Development is a committee under the Little League Baseball Association. Character, Courage and Loyalty is the motto of the Little League and thus the foundation of this program. We aim to provide a safe and fun learning environment outside school hours for kids in need. |

Coach Tom’s efforts, which began in 2002 as a high-performance team, focus on pulling children off the streets and providing them with a safe environment where they can have fun and learn basic life lessons. In 2012 PD changed direction and put more emphasis on the education and behavior. We had members certified to teach Aggression Replacement Training and we began working directly with the Court and SJIS to help get the children in the biggest need off the streets.

|

|||

The

St. Maarten Carnival Development Foundation donated an old office to

be used as the reading area. One of the first set of

books we received was Thomas the Tank Engine. Thus a train set

was needed. The

St. Maarten Carnival Development Foundation donated an old office to

be used as the reading area. One of the first set of

books we received was Thomas the Tank Engine. Thus a train set

was needed. |

|

|||

|

The SMRR started in

1928 as a freight carrier for harvested salt from the Great Salt Pond

to the Philipsburg and Marigot Ports for export shipment worldwide. |

|||

|

|

||||

|

Research can be fun! by Isaiah The

Kids Herald 9/21/2022

|

||||

|

|

||||

Long Island Rail Road first to offer piggy backs

by Malik, age 15 You

have probably seen someone carrying another person on their back.

Sometimes this is called riding piggyback. But if you think about

it…why? Can you imagine a farmer carrying his pig to market on his

back? Me neither. I wanted to know why we call it piggyback, so

I did some research. It turns out that way back in the 1600s carrying

someone on your back was called pick pack. Over time the words slowly

got changed to piggyback. No one seems to know why. You

have probably seen someone carrying another person on their back.

Sometimes this is called riding piggyback. But if you think about

it…why? Can you imagine a farmer carrying his pig to market on his

back? Me neither. I wanted to know why we call it piggyback, so

I did some research. It turns out that way back in the 1600s carrying

someone on your back was called pick pack. Over time the words slowly

got changed to piggyback. No one seems to know why.In the old days, in 1885, the Long Island Rail Road used to run a farmer’s train. Horse drawn wagons hauled goods to market, including live animals like pigs. Everything got put onto the train for transportation to the cities. The goods were held in boxes still in the wagon and were loaded onto the railroad flat cars. The horses were put in the boxcars, and the farmers got to ride in a passenger cars. When they unloaded the train at the city, they would put the wagons, goods and horses back together to continue on to the market. The farmer chose to pay the railroad $4 to put his wooden cart on the train so he could get to the market in as little as two- and one-half hours. Otherwise, it would take the farmer and his horse nearly two days to reach the market. Back in the early days of the Long Island Rail Road, there were no bridges for the trains to get off the island. So, starting in 1880, train cars were loaded on barges and floated across to track connections. It would not be until 1917 when the Hells Gate bridge opened that Long Island trains could connect with the mainland without having to be shipped over on a boat.  This

all leads us back to the railroad’s use of the term piggyback, for

when the back half of a big truck, trailer carrying a container, is

placed right on the train’s flat car. It would later be called TOFC,

for Trailer on Flatcar. But most people still call it piggyback.

Nowadays, the railroads put whole containers on flat cars. They even

have longer cars with a well in the center, so the first car sits

lower almost right on top of the track. This allows the railroad to

stack a second container on top of the other and still pass through

tunnels and under bridges. This

all leads us back to the railroad’s use of the term piggyback, for

when the back half of a big truck, trailer carrying a container, is

placed right on the train’s flat car. It would later be called TOFC,

for Trailer on Flatcar. But most people still call it piggyback.

Nowadays, the railroads put whole containers on flat cars. They even

have longer cars with a well in the center, so the first car sits

lower almost right on top of the track. This allows the railroad to

stack a second container on top of the other and still pass through

tunnels and under bridges.It is easy to load and unload containers if a crane is available. But there are some drop off points that do not have a crane, so the container is left on the trailer and the trailer and container are loaded on the flat car. Some shippers choose to leave the container attached to the trailer even when the final destination has a crane. It is faster and thus cheaper to lift both the trailer and container at one time, place it on the ground, then have a truck connect to the pair and drive off. LIRR was the first railroad to offer piggyback transportation, but now they only transport people, they are out of the freight business. In 1997 they arranged for the New York & Atlantic Railway to carry their freight, using the tracks owned by LIRR. By the early 1900s the farmer’s train no longer hauled horses with wagons. The service switched over to boxcars. Yet the term piggyback remains. I know one thing for sure, if I ever called my sister a piggy, I would be in big trouble with Mom and I would not get dinner! |

||||

|

|

||||

|

Long Island Rail Road helps prevent fatal accidents

with T.R.A.C.K.S.

by Malik, age 15 As bad as that sounds it used to be worse. In 1972 there were 12,000 collisions at highway-rail crossings. Fifty years ago, the state of Idaho started Operation Lifesaver. Just 12 months of educating people about train crossings and the dangers associated with being near train tracks led to a 43 percent decrease in accidents. Soon more states began the Operation Lifesaver. By 1986 the safety program had expanded national wide.

Founded in the west, Operation Lifesaver placed a lot of importance on safety at the crossings. Public service advertisements told people they should not try to beat the closing gates or drive around them trying to avoid long trains. Waits of 20 minutes or more are common. The adverts tell people that although the trains may appear to be going slowly, they are usually moving up to 50 miles per hour and that it takes a train nearly a mile to stop. In 1989, LIRR initiated the Together Railroads and Communities Keeping Safe (TRACKS) program, along with the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) Police Department.

"The TRACKS program provides

customized training to schools, camps, day cares, libraries, and

community groups, stressing the importance of safety at grade

crossings and on our platforms and trains." Not surprisingly, the

TRACKS program is geared toward children, educating them to stay away

from the red flashing lights and signal bells of a railroad crossing.

It offers age appropriate information on how to travel safely using

the system; and the hazards that exist on or near the tracks, this is

according to their website,

https://new.mta.info/agency/long-island-rail-road/lirr-tracks. The LIRR also has posted Emergency Notification Signs at crossings. The signs tell drivers if their vehicle gets stuck on the train tracks at a crossing, they should get out of the car and call the number on the sign. They should give the locator number to the operator. The locator number tells the railroad exactly which crossing is blocked, so the train engineers in the area can start to slow down the train. This way they can avoid a tragic accident before it occurs.

The LIRR and the MTA offer train

safety coloring books and videos. In addition, the LIRR gives to free

talks to students, usually involving the Metro Man Mascot (a silver

looking robot). Toy manufactures have even

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

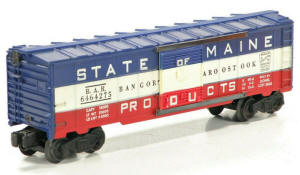

I used to think history was boring – nothing but dates, dates and more dates. So, when I was asked to do a story on the history of the Bangor and Aroostook Railroad, I was not too happy. But I like trains, so I thought that learning more about the history of railroads could be fun.

It was just the beginning – more dates to remember! I learned that BAR traces their origins to 1833. You see, they took over the Bangor and Piscataquis Railroad and the Bangor and Katahsin Iron Works Railway which were founded in 1833. I was almost ready to give up when I discovered that toys can be used to teach history! You see, the Bangor and Aroostook Railroad became famous around 1950. They shipped a lot of potatoes and paper from Maine to places all over the country. They decided they needed new box cars. They bought both new and used railroad cars and painted them – nearly 2,500 cars – red, white and blue. The high visibility cars put the small railroad in the public eye. You see BAR at its peak only operated about 800 miles of track. Yet with 2,500 boxcars to haul a seasonal potato crop, BAR had the second largest fleet of boxcars – second only to the famous Santa Fe line. When the cars were not needed in Maine for the potatoes, the extra cars were rented out to the mid-west to haul produce around the country and all the way to California. The cars were so nice looking, two toy makers made models. The toys ended up under Christmas trees in train sets. Soon other toy manufactures followed. The model red, white and blue boxcars are still available today more than 70 years after the original cars were made. The red, white and blue boxcar features three big horizontal stripes: one blue across the top, the white in the middle and red across the base. Painted in big bold letters on the blue line were the words “STATE OF MAINE.” In the white stripe, across the middle part were the words, “BANGOR AND AROOSTOOK RAILROAD.” In bottom stripe, across the red was just one word, “POTATOES” in all caps. And this is where history gets interesting: You see, after just a few cars were labeled Potatoes, the word was changed to Products. Adults argue a government law made BAR change the word to Products. Other adults claim it was a railroad association guideline, and others say it was just the cars would be used for more than potato hauling and that is why the word was changed to Products. But, come on, I think it was the toy manufactures. What kid wants to haul potatoes around the Christmas tree, when there are Legos and matchbox cars? As for me, I prefer cookies. That way, every time the car comes around, I stop it, open the door, grab a bit of cookies and send the car around again. And to close this history, the dates are still confusing. You see, BAR was sold in 1995 to Iron Road Railways. In 2002, the company went bankrupt (that means ran out of money), but the history people say BAR was no longer in 2003 when they were bought again this time by Montreal, Maine & Atlantic Railway. Go figure. As for me, I like history by toys not dates. It’s a lot more fun. Roger, age 10.

BARs on Long Island Railroad Research by Roger, age

10: Huh? A bar? I know the LIRR had parlor cars, and if you bought a drink and it came in a souvenir glass with Dottie the Dashing Commuter on it, and you got to keep the glass. But it didn't seem to me like there should be a bar in a locomotive. I am just a kid, but I was thinking that was a bad idea. Then I did some more reading, and I found out that BAR stands for Bangor and Aroostook Railroad, the trains from Maine. BAR was known for shipping potatoes, wood and paper. All that could be sent to Long Island, but most railroads kept their engines and just let the other railroads haul the freight cars with their own engines.

After the cooling off period, it was announced that an agreement had been reached. But both the LIRR and the Unions agreed to keep it secret. The Unions did say, “They got everything they asked for.” It was estimated about 10 percent of the commuting passengers never returned to the trains. They had found other ways to get to work and they stuck with their new routines. But the strike had caused another problem. Since the trains had been sitting idle for all those months, and they had not been well maintained during that time, when they tried to get it all back to full service, they found out that nine of their Alco switcher locomotives had frozen up. Their engine blocks had cracked. The locomotives could not be used. Long Island Metro, the official LIRR employee newspaper, reported in issue 29, February – March 1973, that all nine of the damaged engines were scraped. So LIRR asked the Bangor and Aroostook Railroad if they could rent some engines. And BAR said yes. In all, eight BAR engines saw service on Long Island. LIRR also rented engines from Precision National. Three Bangor and Aroostook locomotives were sent on January 21, 1973: the GP-7s BAR 66, BAR 72 and BAR 74. BAR 66 would stay until March 10, 1976 while 72 stayed until April 6, 1977 and 74 returned to Maine April 22, 1977. Engines 62 and 64 were sent to Long Island on January 23, 1973. Both would stay on the island until March 10, 1976. Engine 60 and 65 was sent to LIRR on April 1, 1974 and would stay until March 10, 1976. The last loaner engine, BAR 69, was sent on May 18, 1974 and it would stay in service until April 22, 1977. The Maine Railroad was happy, the lease was a good deal for BAR. They had bought a lot of powerful locomotives for their busy season which had been all about the shipping of potatoes during the winter. In 1969 BAR sent the potatoes in heated box cars to the interchange run by Penn Central. New York Central and the Pennsylvania Railroad had recently merged. In the past, the yard crews keep the box car heaters fueled and running until the cars continued their journey. This year not. The crop was ruined. It would be 40 years before Maine famers would once again ship potatoes by rail. Just to give you an idea of how important potatoes were to the railroad, the 1949 Maine harvest yielded 46,856 boxcar loads of crop. The potatoes were shipped all over the United States. Some were taken to the shipping port and sent off on cargo boats across the Atlantic to Europe. Belgium got 246 boxcars of potatoes and Germany got 1,458. Spain got a lot of Maine's potatoes too: 4,042 boxcars full! So when the potatoes business came to an end, BAR had extra engines. So they were glad to rent them out. But, do not worry they did not lay off the engineers or even rent the crew to the LIRR. I learned that when a train has a lot of cars it may take two, three or even four engines to pull the load, but they still just need one engine crew. The engines are connected together and operated from the lead unit. Oh and when I went back and looked at the book I realized I had seen several BAR engines but they were painted blue and I just thought they were LIRR. It's interesting to learn about all these things that happened back then. And just so you remember the LIRR did not have Bars in their engines.

When is

Number 1 not first? by Roger,

age 10

|

||||

|

|

||||

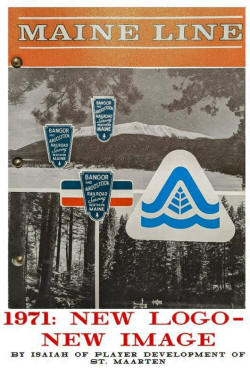

| 1971: NEW LOGO - NEW IMAGE by Isaiah, age 23 Maine Line Magazine - Winter 2022 Editor: Joseph T. “Joey” Kelley | ||||

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Railroad Blue is the Strongest Color

by

Malik, age 15

Traffic lights first appeared in the United States around 1920. Nearly 90 years before the traffic light, Railroads already saw the need for signals to safely control traffic. They devised a flag system to direct engineers when to stop or move the trains. It took a few years for the signals we know and use today to become standardized. Red means stop. Yellow means caution and Green means go. But blue means do not touch a thing. The term 'flag' was carried forward even after the signals became lights for night use. The railroads were not satisfied with red means stop and green go. They needed more. “Railroading is a very dangerous job and people are hurt or killed every year in simple accidents. Some of the worst used to come from fellow employees moving trains while people were working on them,” explained Steven Torborg a Conductor on the Long Island Rail Road who frequently visits St. Maarten.

Basically, there are two times workers go between cars. Workers have

to add cars to or take off cars from a train. This is called coupling

or uncoupling and is done with an engineer on the train who knows

workers are between the cars. The

second and potentially more dangerous situation is when work needs to

be done on a train before the engineer arrives.

Other signals included lanterns and then flashlights for night use. Some railroads used a piece of plastic on a metal rod that could be clipped to the track out in front of the engine. There were fold up and down blue barriers, like those used on St. Maarten for reserve parking.

“The Railroad motto is Safety is of the first importance in the discharge of duty," said Conductor Steve. That is why Blue is the strongest color on the railroad.

M7 interior cab with Employee blue flag ID: "DO NOT OPERATE - MY LIFE IS ON THE LINE"

|

||||

Circus train Blue Flag at Garden City Secondary, Quentin-Roosevelt Blvd. - View NW 5/23/2017 Photo/Archive: Marc Glucksman. |

||||

|

|

||||

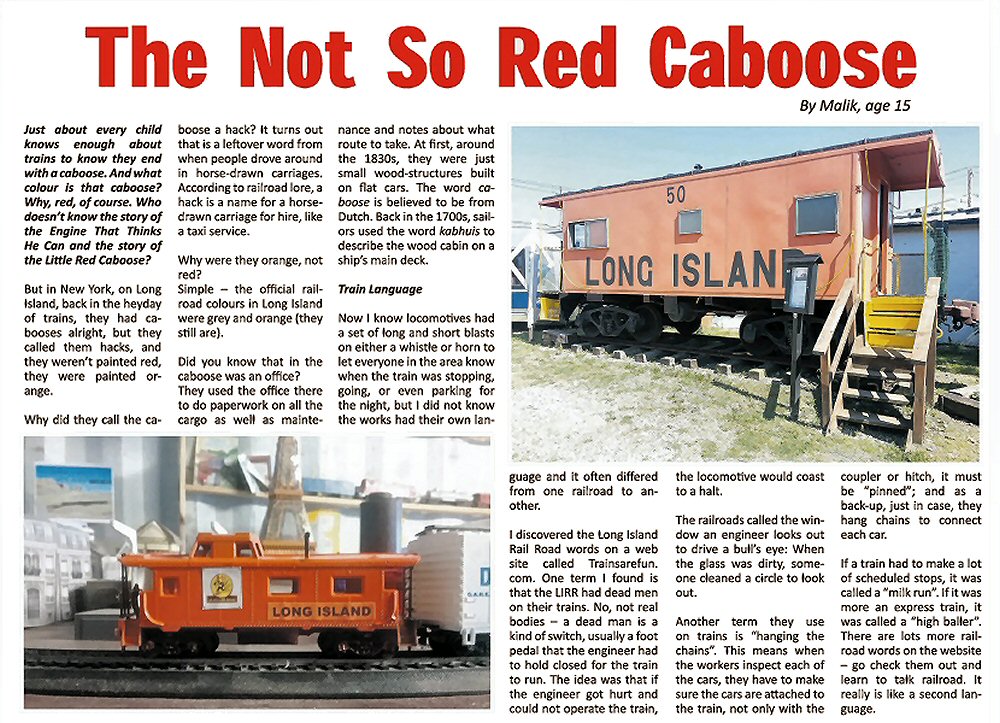

| The Not So Red Caboose by Malik, age 15: | ||||

|

|

||||

|

Diamonds Can Be Dangerous by Collis, age 12: |

||||

|

||||

|

Trains with Three Rails Which came first: 3-rail toy trains or the LIRR? by Roger, Age 11: |

||||

|

Steam engines were the power for early trains. They

burned coal, oil or even wood in the locomotive's firebox to boil

water to make steam. The steam would build up so much pressure that it

was enough to get the wheels to turn and the trains to move along the

tracks. Steam engines made a lot of smoke and dust, so everything

around and on the train ended up dirty. In those days there were two

tracks, and many train tracks are still two rails. That means Lionel had to be working on 3-rail system at the same time that the LIRR was switching to electric. Of course, we do not know if the designers at LIRR ever played with the toy electric trains. The Lionel train set has the third rail in the center of the two tracks with a special roller pick up on the bottom of the trains. The wheels making contact on the outer two rails complete the circuit. So we cannot tell who had the idea of a three rail system first but we are sure glad they did because these are like the ones we have here on St. Maarten at Player Development. They are fun to drive around the track and imagine you are an engineer driving a real train. |

||||

|

Making new toys look antique By Roger, age 11: |

||||

|

Imaging taking a brand-new toy , perhaps a shiny red sports car, out of the box and getting it dirty right away, on purpose. Your mom might get a little made. Maybe not let you bring the toy in the house. Yet that is what model railroaders do. They buy new trains, and make them look old sometimes even before they put them on a track and run them around a bit.

You need to know railroads try to keep the passenger trains looking good. They have wash stations that the cars pass through, so they shine. So we weather just the freight cars. You start with chalk. We use brown and black. Rub the chalk on some 400-grit sandpaper. We do this over a small plastic bowl. The chalk is turned into a fine dust. Next get a small soft bristle paint brush. Dab it into the pile of chalk then dab it on the car. Note we take the car shell off the chaise so as not to get the wheels dirty. On one end of a boxcar there is a wheel on it. It looks like a steering wheel but it is really a brake. Any way it is the back of the car. Once you dab the chalk on the car paying close attention to the ribs of the car you will put more chalk on the brush and lightly start at the front and draw the brush to the back of the car. Riley, at left, and Collis busy weathering the freight cars!

|

||||

This

represents the effect of wind on the moving car. Also weather the roof

and ends of the car. Once the car is weathered, set it down and

look it over. If you are not happy with the weathering get a damp

cloth, wipe the car clean, let it dry and try again. If it came out

good, get a can of Dull-Coat , and gentle spray the car. Start far

back and mist the car. You do not want the spray to blow the car

clean. Once the car is coated let dry. Put the shell back on the

wheels and run the old looker on your layout. This weathering

technique can be used on all kinds of models to make them look more

realistic. This

represents the effect of wind on the moving car. Also weather the roof

and ends of the car. Once the car is weathered, set it down and

look it over. If you are not happy with the weathering get a damp

cloth, wipe the car clean, let it dry and try again. If it came out

good, get a can of Dull-Coat , and gentle spray the car. Start far

back and mist the car. You do not want the spray to blow the car

clean. Once the car is coated let dry. Put the shell back on the

wheels and run the old looker on your layout. This weathering

technique can be used on all kinds of models to make them look more

realistic.

|

||||

| I Have a Toy Railroad Bus By Roger, age 11: | ||||

|

|

|

|||

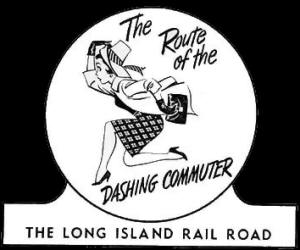

| Dashing Dan and Dottie going strong in 2023 By Roger, age 11: | ||||

|

Happy Birthday to the Long Island Rail Road! It will turn 189 in

April. That is like three or four lifetimes! The ‘road’ was

chartered in 1883. It is so old that the word ‘railroad’ had not been

invented yet. That is why the LIRR has Rail Road in its name as two

words. The LIRR has changed hands a few times since then. The

Pennsylvania Railroad (yes, one word) bought LIRR in 1900 and sold it

in 1965. That’s when the ownership went to the New York Metropolitan

Transit Authority. The symbol that the train sported, its logo,

changed over the years. Under the Pennsylvanian keystone for more than

six decades, then to just the letters ‘LIRR’ and next the letters

‘MTA’ and eventually settling on a circle with the letters ‘MTA’ and

‘Long Island Rail Road’ beneath it.

The biggest change was in power. From coal burning steam engines to

diesel and now third rail electric cars, the LIRR has kept up with the

times and modernized. One thing that commuters and railroad

modelers held onto was the Dashing Dan. Yes, a little fellow with a

briefcase, an umbrella and a funny, I am told fedora, hat can be found

everywhere, despite being retired in 1968. Dan was first introduced to

LIRR employees in their magazine in 1957. He started out in black and

white but by 1958 he had blue business suit on a yellow background. He

is shown running to the left and holding his hat as he runs. Over the

years his direction changed and now he is running right. Also at some

point his shirt was colored white. We have not found a decal of Dottie on the weekend. The pair

retired unceremoniously in 1968. But due to the Covid pandemic, they

were brought back into service. They once again appeared on stickers

and signs in 2020 with the mission to help public health keep safe.

Yes, Dan and Dottie were seen sporting masks to encourage passengers

to mask up. While the pair are not as visible on the railroad in

2023, they are all over E-bay. You can buy Dan hats, shirts, money

clips, belt buckles and even license plates. We even found decals with

railroad spelled as on word and small decals for use on O and even

smaller for HO scale model trains. |

||||

“The Route of the Weekend Chief.” - 1963 |

"The Route of Dash the Robot?" |

|||

| Have you ever seen a steering wheel on a railroad boxcar? By Roger, age 11 | ||||

The

answer is no, but there is something that looks like a steering

wheel. The metal wheel on a boxcar is actually a manual brake.

Years ago the engine was stopped by decreasing the power to the

locomotive's wheels and applying a brake. However the brakes were

not strong enough to stop the whole train. So the train was slowed

and stopped manually with independent brake system on each car.

A brake wheel was placed near the top of the boxcars. Also, on the

top of the boxcars were wooden walkways. This allowed rail crew to

walk or run across one car and jump to next car and apply brakes

particularly when the train was going to go down a hill or going

to stop at a station in town. The roof walks were only 18 to 24

inches wide. The

answer is no, but there is something that looks like a steering

wheel. The metal wheel on a boxcar is actually a manual brake.

Years ago the engine was stopped by decreasing the power to the

locomotive's wheels and applying a brake. However the brakes were

not strong enough to stop the whole train. So the train was slowed

and stopped manually with independent brake system on each car.

A brake wheel was placed near the top of the boxcars. Also, on the

top of the boxcars were wooden walkways. This allowed rail crew to

walk or run across one car and jump to next car and apply brakes

particularly when the train was going to go down a hill or going

to stop at a station in town. The roof walks were only 18 to 24

inches wide.There are still brake wheels are on modern boxcars. But they are no longer used for slowing the train, just to keep the boxcar from moving while it is in storage. These days the trains must have an automatic brake system, whenever they are on the tracks and being pulled. So when the engineer applies the brakes, each car in the consist (that is railroad talk) brakes are applied on each car of the entire train.

According to my good friend Steven Lynch, who runs a railroad

website called

http://www.trainsarefun.com/index.htm the Federal Railway

Administration mandated that beginning in 1966 no new cars could

be built with roof walks. He explained that climbing up on a

moving train, especially if it was wet and slippery, was super

dangerous. It happened a lot that people fell and got hurt. Even

so, change was slow. The idea to remove the walks was first

submitted in 1964. However, it was not until 1968 that the

American Association of Railroads legislated the removal of roof

walks. The last of the roof walks were to be gone by 1979.

I think its cool that the steering-wheel-looking brake system

still appears on box cars. The brake wheels have been placed lower

down so the manual brake can be applied and released from ground

level as the cars are being connected or disconnected from a

train. Not surprisingly, the brake system has continued to

improve. Trains are now being equipped with sensors, both in front

and in back that applies the brakes if something is blocking the

track... like another train. Also, electric brake systems are

replacing air brakes, as compressed air can leak out and cause

braking problems.

So next time you see a boxcar look for the brake wheel and ask

your friend if he thinks he could steer a train from there and

then just laugh and say no that is just a brake! 10/03/2023

|

||||

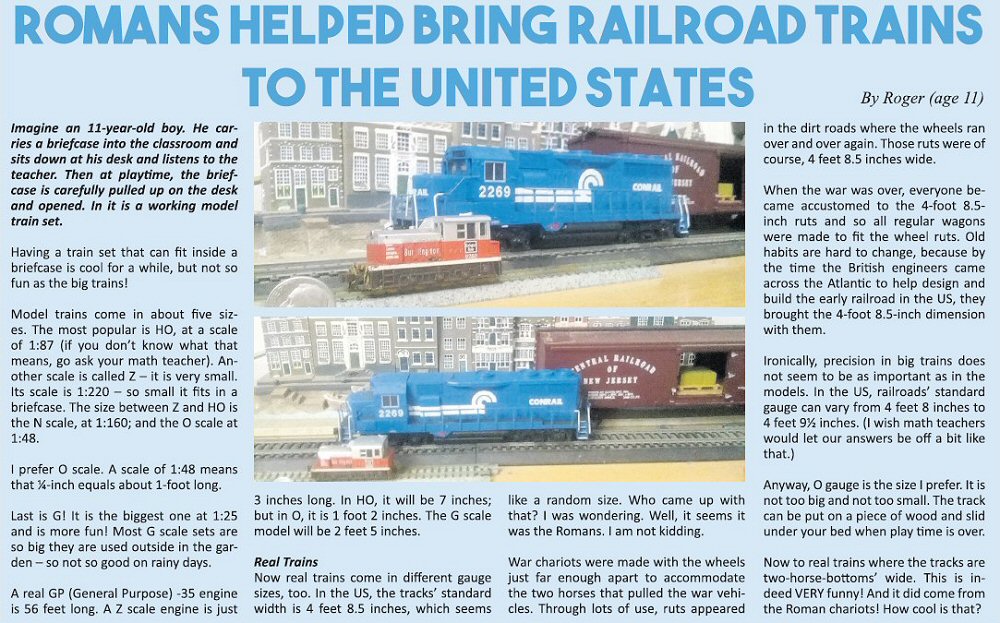

| Romans Helped Bring Railroad Trains To The United States - By Roger, age 11: | ||||

|

|

||||

| Big Boy versus Hudson - By Roger, age 11: | ||||

|

|

||||

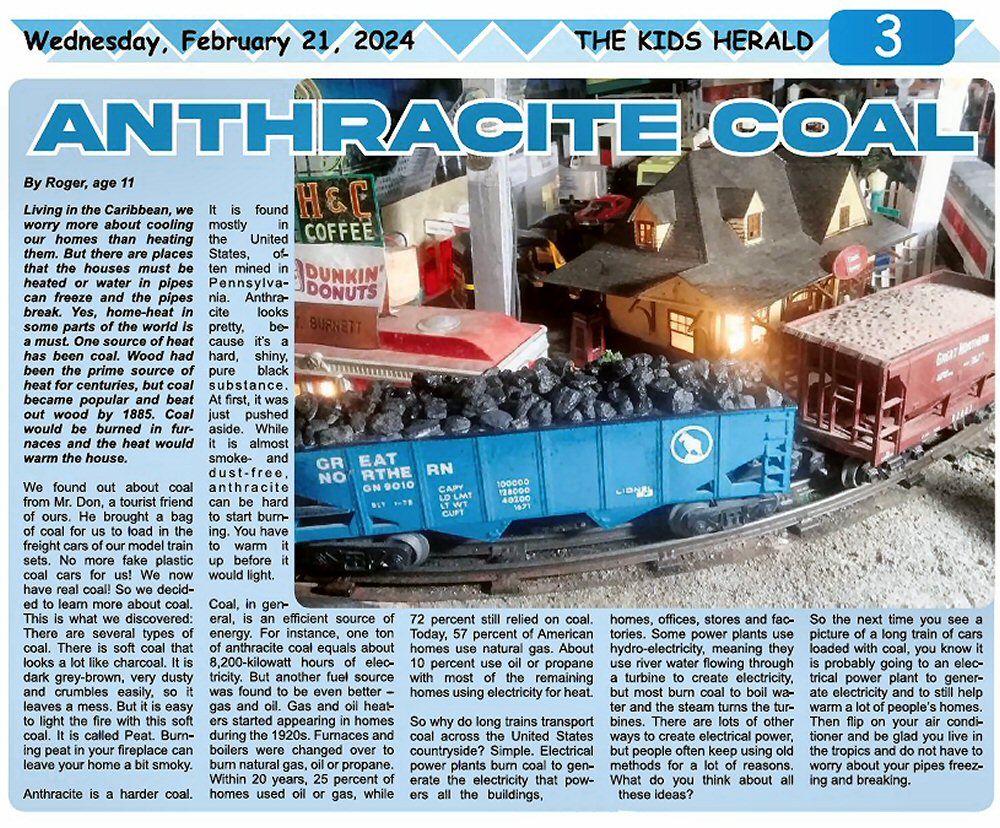

| Anthracite Coal - By Roger, age 11: | ||||

|

|

||||

| Patches - By Riley, age 15: | ||||

Do

you need a patch? No, not for your bike inner tube. I mean

a patch for your jacket or hat. Do

you need a patch? No, not for your bike inner tube. I mean

a patch for your jacket or hat.At Player Development, at the Little League stadium, on Pond Island we do chores like take the trash out or write stories for the newspaper to earn Railroad Patches. Right now we are working on earning patches from The Bangor and Aroostook Railroad of Maine, BAR. BAR was formed in 1891,

and was sold and later declared bankrupt in 2002. Yet we can get three

different patches from the closed railroad. Rail fans, guys and

girls that like looking at, photographing or making model railroads It is fun collecting patches from the different railroads and studying their history. Many started in the 1800s and a few have survived until today. Other smaller less profitable railroads got bought up by big companies like Union Pacific. Yet patches can be found online for even the smallest and oldest railroads. We have two different patches from the Bangor and Aroostook Railroad. We have a white patch in the shape of a triangle. We also have a red white and blue BAR Patch. The BAR has been gone for more than 20 years yet railroad buffs still make model train sets of the line and patches, shirts and even hooded jackets are available online. So next time you see one of us with a patch that says BAR realize we are not going somewhere to drink. We are celebrating the men and women that helped moved people and products and Christmas Trees around the United States. |

||||

We

first started reading Thomas the Tank engine so

the logo had to be a train. A little research led to the GG1. It was

one of the most innovative and long lasting engines made in the United

States. Trains are a fun way Player Development encourages the

children to work hard, learn and then play.

We

first started reading Thomas the Tank engine so

the logo had to be a train. A little research led to the GG1. It was

one of the most innovative and long lasting engines made in the United

States. Trains are a fun way Player Development encourages the

children to work hard, learn and then play.

"Operation

Lifesaver has been committed to preventing collisions, injuries and

fatalities on and around railroad tracks and highway-rail grade

crossings, with the support of public education programs in states

across the U.S.,” according to their website

"Operation

Lifesaver has been committed to preventing collisions, injuries and

fatalities on and around railroad tracks and highway-rail grade

crossings, with the support of public education programs in states

across the U.S.,” according to their website

Toy history is

much more fun than dates

by Roger, age 10

Toy history is

much more fun than dates

by Roger, age 10