The first written evidence of the usage of caboose in a railroad context appeared in 1859 (not 1861, as cited by the Online Etymology Dictionary), as part of court records in conjunction with a lawsuit filed against the New York and Harlem Railway. This suggests that caboose was probably in circulation among North American railroaders well before the mid-nineteenth century.

The railroad historian David L. Joslyn, a retired Southern Pacific Railroad draftsman, has connected caboose to kabhuis, a Middle Dutch word referring to the compartment on a sailing ship's main deck in which meals were prepared. Kabhuis is believed to have entered the Dutch language circa 1747 as a derivation of the obsolete Low German word kabhuse, which also described "wooden cabin" erected on a ship's main deck. However, further research indicates that this relationship was more indirect than that described by Joslyn.

Eighteenth century French naval records make reference to a cambose or camboose, which term described the food preparation cabin on a ship's main deck, as well as the range within. The latter sense apparently entered American naval terminology around time of the construction of the USS Constitution, whose wood-burning food preparation stove is officially referred to as the camboose. These nautical usages are now obsolete: camboose and kabhuis became the galley when meal preparation was moved below deck, camboose the stove became the galley range, and kabhuis the cookshack morphed into kombuis, which means kitchen in Afrikaans.

It is likely that camboose was borrowed by American sailors who had come into contact with their French counterparts during the American Revolution (recall that France was an ally and provided crucial naval support during the conflict). A New English Dictionary citation from the 1940s indicates that camboose entered English language literature in a New York Chronicle article from 1805 describing a New England shipwreck, in which it was reported that "[Survivor] William Duncan drifted aboard the canboose [sic]." From this it could be concluded that camboose was part of American English by the time the first railroads were constructed. As the first cabooses were wooden shanties erected on flat cars (as early as the 1830s) they would have resembled the cook shack on the (relatively flat) deck of a ship, explaining the adoption and subsequent corruption of the nautical term.

There is some disagreement on what constitutes the proper plural form of the word "caboose." Similar words, like goose (pluralized as "geese"), and moose (pluralized as "moose," no change) point to the reason for the difficulty in coming to a consensus. The most common pluralization of caboose is "cabooses," with some arguing that this is incorrect, and, as with the word moose, it should stay the same in plural form—that is, "caboose" should represent one or many. A less-seriously used pluralization of the word is "cabeese," following the pluralization rule for the word goose, which is "geese." This particular form is almost universally used in an attempt at humor (as, presumably, are "cabice" and "caboosii"). Source: Wikipedia

FRED, The End of an Era

Until the 1980s, laws in the United States and Canada required that all freight trains have a caboose. Technology eventually advanced such that a caboose was unnecessary; improved bearings and lineside detectors to detect hot boxes, better designed cars to avoid problems with the load. The final nail for the caboose's coffin came with an electronic box with the innocent name of "FRED," an acronym for flashing rear-end device, or "EOT," End-of-Train device. A FRED/EOT could be attached to the rear of the train to detect the train's air brake pressure and report any problems back to the locomotive. The FRED/EOT also detects movement of the train upon start-up and radios this information to the engineer so that he/she will know that all of the slack is out of the couplings and additional power can now be applied. With the FRED/EOT on the job the conductor moved up to the front of the train with the engineer and year by year, cabooses started to fade away. Very few cabooses remain in operation today.

A while back there was mention in a thread about where the term 'hack' came from in reference to a caboose. I don't think anyone knew where it came from, and after asking JJ Earl about it, he didn't know either, saying that's just what it was called. Yesterday I was at the LI Museum in Stony Brook and they have a stage coach from 1860 that was a smaller version of the more common, larger one. This smaller one was called a Hack Passenger Wagon. I figured that freight crews back in the late 1800s must have used the term hack to refer to the caboose since it's the 'passenger' carrying car of a freight train.

LIRR Cabooses called

"Hacks"

The Pennsylvania Railroad and LIRR officially referred to cabooses as "cabin cars".

LIRR hacks were used as a freight conductor’s office even with their own desk built into the wall to do their paperwork. The desk was even illuminated by a wall-mounted kerosene lamp in some cases. These desks and lamps were still in place in some hacks as late as the mid-1970s.

Cabooses, in general, were used as bunk houses for the crew which usually consisted of the freight conductor and two freight brakemen. As the LIRR was a short-distance road, unlike the Pennsy which had freights that could’ve run overnight, they may have had no need to use their bunks and they may even have been removed over the years and used for storage, but originally the intent of the bunks was for crews to rest.

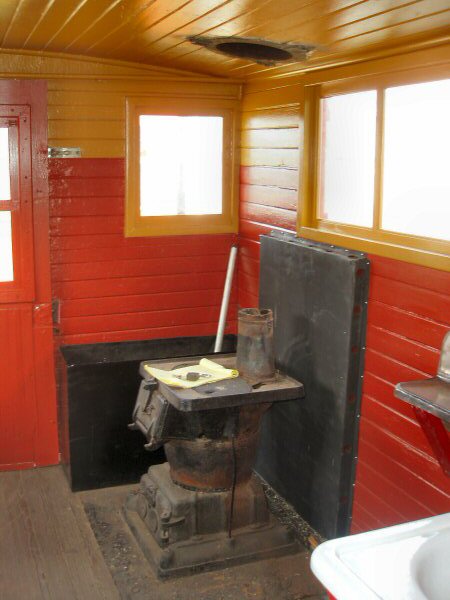

LIRR hacks were used to cook meals and were quite good. Personally, I never had a meal cooked on a pot belly stove. Of course in later years, the cooking ceased in the cars, but they did at one time cook meals. This cooking was done over the coal fired, cast-iron stove that was located in each of the older hacks. Contrary to some belief, those stoves were not installed specifically for heat, although they did provide heat for the car while the hack was not connected to the train during switching and while in the yard prior to a run.

LIRR #12 Coal stove sans flue

As you can see, this is a stove with large, flat cooking surface on top and not a stove that was provided solely for heating. Also notice the cast-iron back stop to keep spatter as well as grease fires from scorching the walls of the hack.

The steel hacks were

equipped by the crews with Coleman Gasoline stoves which were quite

reliable. It was usually the flagman's job to prepare the meals.

Concerning the crew consist; two brakemen were used on most MA trains and

three were required on any MA job where a cross over move was part of

their regular routine; think

The pot belly stove in #12 hack was used for heat during winter and that it did have an exhaust stack connected to the outdoors. Info: J.J. Earl

LIRR #12 06/24/1956 Photo: Art Huneke

LIRR Caboose #14 at Greenport

Museum RMLI September 21, 2002 dedication day. Photo/Info: Don Fisher

In the earliest days the

bunks were indeed used for overnights at the end of the line. As

time progressed, the crews on both freight and passenger consists that

laid over in Greenport were given room and board "chits" and

went up the street to one of the hotels or rooming houses for the night.

Then there were the individual conductors who "owned" their

hack.

Stories go that one conductor had to have his caboose turned on the

Greenport turntable ASAP after arrival. The car was then shoved out

onto the end of the long railroad dock for the evening. He was an

avid fisherman and spent the time fishing off the dock and preparing a

mess of fish for the next days trip west. In the summer the cool bay

breezes kept his hack cool on the hottest of nights and during WWII, when

the Coast Guard patrol boats would tie up for the night, they would throw

him an electric line from the boat so he could have electric light to read

and cook by. To a protective conductor, his hack was his home and he

did everything he could to delay the car going into the shops for a big

overhaul. They hated to give up their home for an annual cleaning

and paint job!

Then there was the part Native American Brakie who shot fresh dinner meat

as the freight train rambled through the Pine Barrens. One trip they

had a newbie conductor on board.

As he was working at his desk, he didn't notice Brakie grabbing the rifle

out of his locker and ascending the ladder to the roof of the hack. Soon,

shots rang out and Brakie descended to go grab his squirrel only to be met

by a ghost white conductor who thought the train was being held up! I

guess you had to be there but it was a cussing good time. Story goes

the Brakie's squirrel stew - slow cooked over the coal stove - was THE

BEST!

Info: Bob

"Ducky" Kaelin of Southold, NY He was a kid at the time and rode

the hacks from Riverhead to Greenport with the many freight crews that

came out this way.

The Montauk freight went close to Indian owned property. The population of the reservation included a few Indians that were Gandy Dancers that first worked out of Hicksville and then later on out of Riverhead. I had the privilege to work with them when I was 16 years old. When I went into engine service it was a regular duty ,of mine, to call the men I knew, to tell them where we hit deer, after Amaganset. They always met the train on the way west to deliver steaks and roasts. I never got squirrel steaks.

There was a retired Conductor at Amaganset that met the eastbound passenger trains that took orders for Bay Scallops and delivered them, by the quart, on the westbound. They cost $2.50 a qt in cardboard containers. The engineer Tommy Rome, had a standing order for 3 qts every time he went east. It was a tough timetable to get the scallops on the right day, The Montauk ran 7 days on and 3 days off. By the way, I have never had a bad meal in a Hack.

Info: Ed Schleyer

Photos are from LIRR Caboose #14 at Greenport RMLI

Courtesy: Don Fisher

Caboose Slang Terms

Of all the implements of railroading, none has had more nicknames than the caboose. Many are of American or Canadian origin and seek to describe the vehicle or its occupants in derisive ways. Often heard amongst crews was "crummy" (as in a crummy place to live, not elegant, often too hot or too cold, and perhaps not especially clean), "clown wagon," "hack," "waycar," "dog house," "go cart," "glory wagon," "monkey wagon" (a term that indirectly insulted the principal functionary who rode therein, no doubt coined by an engineer), "brain box" (the conductor was supposedly the brains of the train, as opposed to the "hogger" or engineer, who was presumed to be pigheaded), "palace," "buggy" (Boston & Maine/Maine Central), "van" (Eastern and Central Canada, usage possibly derived from the UK term for the caboose), and "cabin", or a variation heard at least on the Southern Railway, "cab". There were others as well, some too profane to appear in print.

The small, two-axle cabooses that were widely used during the latter part of the nineteenth century were called "bobbers," which term described their riding characteristics on the relatively uneven track of the time. Bobbers tended to produce an unpleasant pitching motion that was usually not present in more modern, two truck models.

From http://www.reference.com/browse/wiki/Station_wagon:

The first station wagons were a product of the age of train travel. They were originally called 'depot hacks' because they worked around train depots as hacks (short for hackney carriage, an old name for taxis). They also came to be known as 'carryalls' and 'suburbans'. The name 'station wagon' is a derivative of 'depot hack'; it was a wagon that carried people and luggage from the train station to various local destinations.

From http://www.oldwoodies.com/resource-woodies-terms.htm:

Depot Hack - A passenger carrying wagon for hire commonly found at American train depots in the first half of the 20th century.

From http://www.mcq.org/presse/aacb_obj.html:

Hack Passenger Wagon - Up until 1893, the Concord stagecoach was the principal means of transportation in the West. First built in 1820 in the workshops of the J. S. Abbot & Son Company in Concord, New Hampshire, it seated 16 passengers inside and on the roof. After 1893, its

successor was a lighter and therefore faster stagecoach, but not as sturdy. The new model was for short distances on fairly level terrain.

Research: Al Castelli