The Growth and Decline of the Long Island Rail Road Freight Traffic In Suffolk County

LONG ISLAND

SUNRISE TRAIL by Michael Bartley

In 1844 the Long Island Rail Road

reached Greenport from Brooklyn, a distance of 95 miles at a cost of

$1,730,000. It was surprising that

Greenport, a town that only received its name in 1831, was chosen by the LIRR

as its terminal instead of Sag Harbor. The 1834 charter of the LIRR authorized

construction to Sag Harbor from the main line. Sag Harbor was already an international

major deep water port. The Sag Harbor

port in 1789 did more business with shipping than New York City. And Sag Harbor was the most populated,

prosperous village in the eastern end of Long Island with the whaling industry

reaching its peak in 1840’s. The Villages of Bridgehampton, Southampton, and

East Hampton were all flourishing at the time with agricultural and raising

stock. Yet Sag Harbor was not connected by steel rail until May 1870 and the

line was abandoned in 1939 both due to financial problems with the LIRR. But besides the politics back in the day,

Greenport had no hills and with no grade it was easy and inexpensive to build level tracks to Greenport than to Sag

Harbor. The objective of the LIRR was to shorten the travel time between New

York and Boston by using a rail-boat-rail route instead of a stagecoach ride or

a boat trip.[1] This connection saved over 5 hours of travel

from using a steamboat between the two cities.

The LIRR made a lot of revenue for example in 1844 the freight income of

the LIRR was $10,154. And at the time the railroad was one of the most heavily

traveled railroad in the world. But

after a few years the New York, New Haven and Hartford Rail Road did what was

considered impossible by engineers. The

New Haven Rail Road completed laying tracks between New York and Boston by

building over marshes, hills and rivers in Connecticut.

By 1850 the LIRR found itself

bankrupt with the mainline along barren land.

The LIRR was forced to build branches in order to link the towns of the

North Shore and South Shore of Long Island into a transportation network. The

LIRR created a demand for its services by tapping into the rural agricultural

areas of Long Island, as well as the fishing industry. The LIRR competed with both the North Shore

and South Shore Ships that were transporting commerce to and from New York

City. Since the railroad was faster

than ships and wagons, the railroad became another choice to ship or travel to

and from New York City.

Up to the Civil War cordwood was a major

source of revenue for the railroad to transport to New York City for people to

use as source of home heating fuel before coal became more common.[2] Farmers who were clearing their land would

bring the wood to trackside locations buy wagon for the railroad to ship to the

city. And the LIRR on Eastern trips

would haul back wood ash and horse manure as fertilizer. In 1852 the LIRR

freight business earned $58,000. And in 1863 the LIRR freight business grew for

a total of $121,000.

The LIRR struggled along until

Austin Corbin became President in 1880.

The reforms made under his leadership such as upgrading the rail road

equipment by replacing the stove heated open platform coaches with new steam

heated and modern coaches. New steel

rails replaced iron rail, narrow gauge lines were replaced with standard gauge.

New safety signals were introduced along with more larger- more powerful

locomotives. President Corbin unified the railroad into a well-organized system

which earned the LIRR a profit of $500,000 in 1886. He extended the railroad

eastward to Montauk with the idea of saving travel time (almost 2 full days)

between New York and London by making Montauk a deep water port for

transatlantic vessels and having the passengers as well as mail travel by train

both to and from New York. In 1896, a year after Montauk was connected to

Brooklyn by steel rail Congress in Washington was debating the idea of Corbin’s

dream. Unfortunately President Corbin

was killed in an accident. His dream of a deep water port in Montauk also died

with him.

LIRR car float # 20 perhaps on its

way to the North Shore Yard (LI City Float).

LIRR car float # 20 perhaps on its

way to the North Shore Yard (LI City Float).

The Fishing Industry

In the late 1800’s a source of freight traffic was along the Great South Bay with over 25 oyster packing houses. In 1880 the LIRR shipped 520 barrels of oysters from Patchogue each week. Oakdale was shipping 805 barrels by the LIRR and Sayville shipped 70 barrels a week . The LIRR was used extensively, along with boats and wagons to transport the shellfish to New York. The principal shipping points for the oyster packing houses since 1890 that was used by the LIRR was Babylon, Bayshore, Oakdale, Sayville and Patchogue. The LIRR hauled 60 to 70 barrels of oysters each year from these packing houses. Once the packing houses would receive oysters from local Bayman they would “shuck” the oysters and the meat would be put into gallon and ½ gallon wooden kegs along with ice. These wooden kegs would be brought by wagon to the LIRR and loaded onto Baggage Express cars and shipped to New York City.

Greenport was known as the heart of the oyster industry. There were over 30 canneries churning out galvanized tins of oysters. The LIRR had up to 4 express trains a day carrying oysters to New York by 1890’s. Train # 62 would leave Greenport at 7:00Am, Train # 146 leave at 2:05PM, Train # 34 leave at 2:25Pm and Train # 110 leave Greenport at 7:46PM. The railroad also hauled wooden barrels that had up to 3 bushels of half shell oysters which could weigh about 250 pounds. But with better more improved roads built on Long Island during the 1920’s and 1930’s more trucks were taking over the transportation of oysters.

1948

Express car no. 623 being loaded with oysters from truck for New York

Restaurants at Greenport Station. Robert Emery photo, Robert Emery Collection

(courtesy of Stony Brook University).

The 1938 Hurricane created a new inlet in the Great South Bay which covered the oysterbeds with sand and mud. The Sealshipt Oyster Company, which bought over smaller oyster companies and combines them into a very large corporation and renamed the Bluepoints began planting seed oysters in Oyster Bay, the Peconics and other communities. But by the 1950’s oyster harvesting was virtually suspended due to a combination of over harvesting, pollution, oyster diseases. And in 1985 a mysterious Brown tide hit the Great South Bay which decimated the bay’s scallop and clam population which caused the Bluepoints to cease operations.

Fish Oil

Over a period of time with a large number of complaints about the fish smell New York State passed a Health Law that forced the closing of these plants and relocated some plants to different areas. One area of Long Island in 1873 that was unfit for farming due to sandy soil was Napeaque (Promised Land) between Montauk and Amagansett which was uninhabited and also had deep water so that a port could be built.

Bunker oil was promoted as coal miner’s lamp fuel, a lubricant for machinery, an additive to paint, cosmetics, linoleum, margine, soap, and insectides, and what was left over after the oil was cooked out of the fish could be used for animal feed.[3]

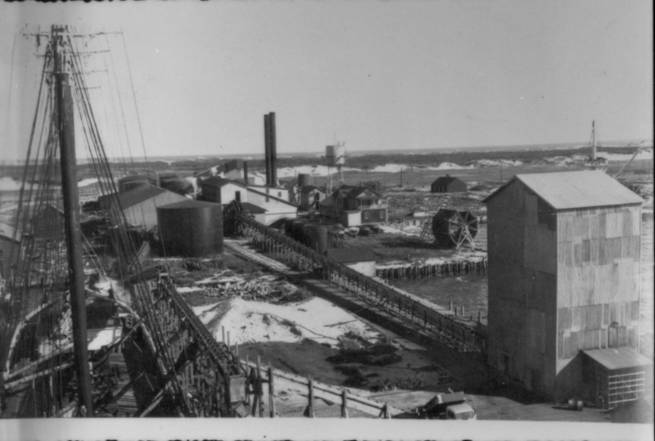

By 1881 there were more than 350 ships supplying menhaden to 97 fish factories in the East End that employed more than 2,800 people. In 1898 a British and American consortium decided to invest in the bunker fishing trade. They formed a company named American Fisheries Company and bought most of the fish factories from Maine to the East End of Long Island, creating a monopoly in the industry. At Promised Land they bought all 7 fish factories that were there. The LIRR built a large freight yard and a freight station in Promised Land for the American Fisheries Company. A fire the next year destroyed the freight station along with some freight cars.

Due to overfishing of bunkers, the American Fisheries Company reorganized in 1900. Another fire at one of the Promised Land factories in 1907 caused the American Fisheries Company to go bankrupt. The plant closed down in 1926. The Hayes and Anderson Fishers Product plant was destroyed by fire in 1930 leaving only one remaining factory in Promised Land- the Triton Oil and Fertilizer Company which was purchased by Gilbert P. Smith. He owned a number of processing plants along the East Coast. Mr. Smith upgraded and modernized the fish meal factory. He owned a fleet of 17 fishing boats that was based in Greenport to fish for the Bunkers along the East Coast from Massachusetts to North Carolina. After World War Two he also used four Piper Cub aircraft that flew out of the Hamptons to aid in searching for Bunkers and radio to the ship the location of the schools that were seen. [4] The boats would be out for a week trapping fish in their nets during the fishing season between April and October when the fish meal factory was opened.

During this time millions of bunker’s were unloaded at the Promised Land Factory dock and then boiled in huge vats and crushed by huge rollers. The fish oil was then piped into large storage tanks and later shipped out by rail road tank cars. The fish meal, which was left over pulp and bone, was a high protein supplement for animal feed. It would be blown into boxcar roof hatches[5] and also shipped by the LIRR westward to Holban Yard and beyond. The LIRR also shipped bulk fuel to the fish factory. The Smith Fish Meal factory closed in 1968 and that ended the Long Island Bunker Fishing Industry.

Smith’s

fish meal factory at Promised Land, notice warehouse, water tank, fish oil

storage tanks, dock. Photographer unknown

LIRR

Baggage car used for shipping fish to Fulton Market-notice many wooden boxes

used for shipping from Montauk 1935. Robert Emery photo, Robert Emery

Collection (courtesy of Stony Brook University).

Once the LIRR reached Montauk a rail road dock was also built that had a 6 car capacity. The LIRR would line up boxcars, reefers and express baggage cars on the dock so that fishing ships could transfer loads of fish which were in iced wooden barrels and wooden crates daily to NY City. Baggage cars would be loaded with up to 150 wooden boxes of fish packed in ice that would weigh in at 200 pounds each. All the fish shipped to Fulton Market in New York City by The LIRR would be loaded from the rail road dock. The Rail Road dock had a crane that was used to load the boxes onto the trains. The LIRR also used the dock to unload hoppers filled with coal to their Montauk Steam Boat Company Ships.

1901 LIRR Montauk Dock Express car and ventilated Box

Car No. 765. This dock was used to load Railroad cars directly from fishing

boats and the wooden boxes were used to hold ice and fish for the shipments.

Robert Emery photo, Robert Emery Collection, (courtesy of Stony Brook

University).

The village of Montauk during the 1890’s was located along Fort Pond Bay near the Montauk LIRR train station. The village had about 100 small homes where the fishing captains and crews lived. The village had fishing facilities that included fishing piers, warehouses, fish packing houses, sheds , shanties, and an ice house built all along the shore line. All around the village were wooden boxes built by the fishermen used to ship fish. By 1901 Montauk was becoming a growing commercial fishing port. And the LIRR was the reason why Montauk became the principal fish shipping port on the East End. Train loads of cod, sea bass, striped bass and herring would be shipped daily by the LIRR to New York Markets. In 1903 alone, the LIRR shipped 250,000 tons of fresh fish which included cod, bluefish, weakfish, bass and flounder from both the North and South Forks. From Center Moriches, East Moriches, Brookhaven and Eastport over 30,000 barrels of crab and thousands of wooden boxes of scallops were transported to the Fulton Fish Market by the LIRR. The Fish Venders in Montauk which sold fish to the agents of the New York Fish Markets would label the wooden shipping boxes with their name such as Tuthill, Duryea, and Wells.

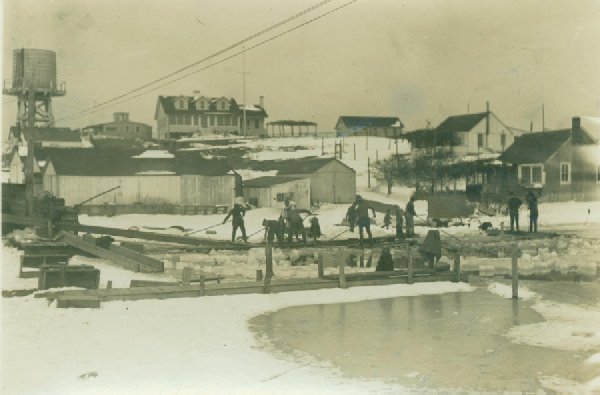

Montauk Ice Harvesting at the Fishing Village. Photographer unknown

Between the years 1920’s and 1930’s the Montauk fishing village became a year round community with a great increase in commercial and recreational fishing. More better built homes, the Union News Dock and restaurant was built in 1933, the LIRR even ran a spur to it the same year. The Union News Dock was used for fishing excursions and Steamboat trips to New London Ct. in the summertime. A lot of changes in Montauk happened after Carl Fisher came to Montauk in 1926. No longer were sheep herders around, but there was still cattle in Montauk. With all Carl Fishers building projects such as the Montauk Manor, Montauk Yacht Club, Montauk Downs Golf Course, and the Montauk Improvement Office Building. The Montauk Beach Development Corp. built a supply warehouse in 1927 along the LIRR tracks in Montauk which the LIRR shipped building supplies. It was during 1933 that the LIRR started the famous “Fisherman’s Special” which brand people from New York City during the fishing season on weekends to Montauk to fish all day. The LIRR had a baggage car that was equipped with ice bunkers to keep fish that was caught cold on the return trip to NY. In 1934 over 20,000 people took these trips, and that was during the Great Depression.

The Hurricane of 1938 wrecked the fishing village of Montauk and forced boat captains to relocate to Montauk Point village docks. When the United States entered World War Two after Pearl Harbor was bombed both the U.S. Army and the U.S. Navy took control of Montauk. The LIRR relocated both the passenger and freight station in Feb. 1942 and torn down the rail road dock in Montauk. The Fishing village also was torn down since the U.S. Navy took over the entire shoreline of Fort Pond Bay for use as a testing facility area for naval torpedoes. Huge concrete hangers and shops replaced the homes and shops of the old fishing village. The LIRR would run Baggage and Express cars with no passenger’s during 1942-1946.

LIRR Montauk

dock fishing boats transferring fish to Reefers for shipping to Fulton Market.

Photographer unknown

Between 1881-1900 the LIRR freight business was constantly growing and accounted for at least 1/3 of the revenue earned by the rail road. In twenty years a large income came from the transporting of seafood and agriculture from Long Island to New York City. In 1893 the LIRR earned over $1,370,000.

The rail road built new freight houses, and larger pier facilities along the East River. The LIRR started running larger freight trains during this period. In 1890 the LIRR Express Department Building was built in Long Island City. The Greenport terminal was upgraded in 1892 which included improvements at the dock, a new passenger station, and a brick freight house was built.

By the beginning of the 1900’s the LIRR was hauling 300,000 freight cars a year. And the LIRR was operating its own express and delivery service. The Long Island Express Company was formed in 1882 by the LIRR to handle local baggage and express shipments. This company in 1913 became part of a national express business named the Adams Express Company. In 1918 with the United States Railway Administration (USRA) in charge of the Nation’s Rail Roads a merger of the Adams Railway Express Co, American Express Co, Southern Express co, and Wells Fargo & Co Express and was named the American Railway Express Co. The name was changed in 1926 to the Railway Express Agency which was owned by 86 American Rail Roads. The LIRR had Express Agency Offices and Freight houses along with their passenger stations. At Montauk it was common for agents to handle up to four express trains carrying loads of fish to westbound markets. In 1896 the largest shipment done up to that time by the Long Island Express Co. was 153 barrels of Cauliflower that was shipped to New York City.

Riverhead 1950 Emery

Collection photo: Dave Morrison (courtesy of Steven Lynch, www.trainsarefun.com). Riverhead

1950, Robert Emery Collection, Courtesy of Stony Brook University.

In the 1880’s Cauliflower was considered a delicacy in New York City and the market price at the time was $1.50 a head.[6] And the largest growers of Cauliflower were Riverhead and Southold. In 1890 the Town of Riverhead’s official census was 4,000 people. And yet Riverhead was becoming the agriculture hub of the East End. The LIRR along with the farmers was the main factor that Riverhead was earning that title. Many farmers at this time had families dating back before the American Revolution who have been working the land in the East End. And after the LIRR came to the East End in the 1840’s Irish Immigrations followed the rail road to find work. Within a few decades more Europeans such as Germans and Polish settled in Riverhead to earn a living farming. The LIRR was instrumental in the development of Riverhead, as well as the rest of Long Island.

There were a few organizations that were formed in Riverhead that had a huge impact in the agriculture industry. The oldest one was formed in 1863 by a group of farmers to form a club promoting agriculture. Meetings were held to discuss different kinds of seeds, and what type of crops were the most profitable to grow. This club was called the Riverhead Town Agricultural Society and was the oldest farm cooperative group in the United States. When commercially mixed fertilizers became available the Society acted as purchasing agents for its members and get bids and contracts for delivery of fertilizer at the lowest price. In 1872 the society bought a 1 pound bag of Algiers Cauliflower seed and this is what started the East End to become the largest growers of Cauliflower east of the Mississippi River with over 1/3 of Cauliflower grown in the United States in the Towns of Riverhead and Southold.[7]

In 1901 a few farmers formed the Long island Cauliflower Association. The LICA was a cooperative that would buy cauliflower seed at the lowest price possible, supplying barrels and later wooden crates to it farmers and working out reduced shipping cost’s with the LIRR by filling up more reefers. The LICA had a better system of marketing cauliflower and have agents in New York City selling the crop.

During harvest time which was between September and October before any frost the LICA would have a daily auction both in Riverhead and Southold. Farmers would line up their wagons filled with special ventilated barrels allowing air to circulate packed with up to 12 head of cauliflower. It was up to the farmer once his crop was inspected and given a market price to decide if he wanted the LICA to purchase his cauliflower. The LICA would give a receipt to the farmer and it would be the responsibly of the LICA to sell the crop and pay the farmer. The cauliflower would be loaded into iced reefers and the LIRR would run the cars to the city market.

During 1903 the LICA shipped 285,000 barrels of cauliflower, as well as 300 carloads of potatoes. Each year the LIRR would ship to New York thousands of barrels of pickles, onions, asparagus, cabbage and cranberries. In a short time period the LIRR would be shipping over a million bushels of potatoes from the farms of East Hampton and Southampton. During this time also the LIRR hauled thousands of bushels of lima beans from farms between Deer Park and Riverhead.

In 1936 the LIRR shipped 667 reefers of cauliflower and in 1937 there were over 1,054 car loads of cauliflower. These reefers needed to be iced. And in the age before mechanical refrigeration the typical refrigerator was heavily insulated with bunkers at each end of the car to hold blocks of ice. The ice would be loaded into the bunkers through roof top hatches. To supply ice to these cars in the late 1800’s up to the manufacture of “artificial” ice Long Islanders during the early part of the 20th century. East End farmers and fisherman as well as the rest of communities worked together in the winter time when ponds, lakes, and rivers were frozen in the task of ice harvesting. They would cut blocks of ice out of the frozen water using saws just like the type of saws lumberjacks had. These ice blocks then would be loaded onto wagons and stored in well insulated wooden warehouses. The ice would be well packed together with sawdust and remained frozen throughout the spring and summer and be used for harvest time. William Sweezy of Riverhead formed the Long Island Ice company. Overtime the Long Island Ice company would have 7 locations on Long Island. In 1928 a modern Ice house and warehouse with a 2 car capacity was built in Riverhead. During harvest time the LIRR leased reefers would be loaded with blocks of ice from the LI Ice co.

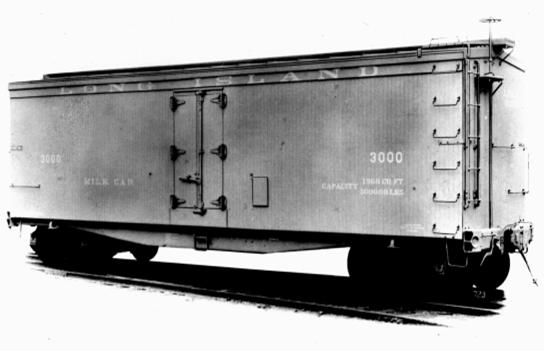

In the late 1800’s Long Island dairy farms, benefiting from inadequate methods of refrigeration that kept upstate producers out of the business at the time, did a booming business by supplying milk quickly to the vast New York population. Westbury during the 1880’s was the largest and most important milk station on the LIRR. The largest dairy farm east of Westbury was the Silberstien Brothers which had 300 dairy cows located in East Northport. Also using the LIRR was the Clover Leaf Creamery located along the tracks a ½ mile east of Northport train station. The creamery would make butter from milk delivered by local farms around the area and ship by train to locations all over Long Island from Brooklyn to Riverhead. The LIRR being the fastest way to transport milk, would use baggage express cars for those 40 quart cans of milk to deliver to large processing plants such as Sheffield Farms. In Hampton Bays Sheffield Farms built a bulk plant in 1931. The LIRR used the 2 car siding at the plant to daily drop off Express Reefers. Patchogue would use Express Reefers to exchange milk cans at its Freight House for the Sheffield Farms Plant during the 1940’s. Dairy farms all over Long Island kept the LIRR busy carrying milk everyday.

Another major part of agriculture that was big on Long Island at the turn of the century was the pickling industry. On the Port Jefferson Branch alone there were four pickle houses. One of the largest was the Rothman’s Pickle Works that was located just opposite the Northport train station. The pickle house was built in 1892 and operated until 1961. The plant had a 14car rail road siding and employed 60 people producing 15,000 barrels of sauerkraut at a time. On site at the pickle processing factory was a brine salt warehouse, both a sauerkraut vat shed and a pickle vat shed. The vat was 8 feet deep and filled with 6 inches of brine. Wooden barrels would be cleaned by steam, and processed pickles as well as processed sauerkraut, would be packed in the barrels and cured. Farmers that grew cucumbers and cabbage would bring their crops to the factories at harvest time until the first heavy frost would arrive in the fall season and put an end to production. The Rothman’s Pickles were distributed throughout the Northeast region until the lack of access to cucumbers and cabbage became a problem due to more farms being sold for new homes constructed.[8]

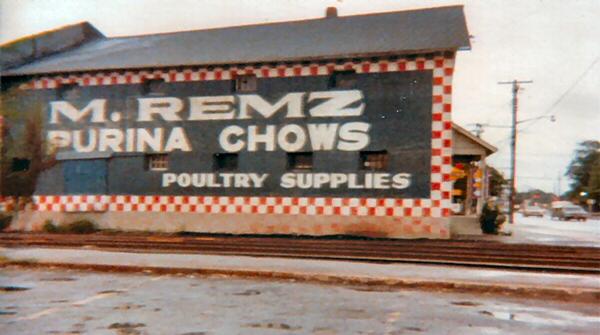

The LIRR earned revenue hauling this type of freight until the mid 1940’s when more trucks took over the transportation of garden crops grown on Long Island. In Port Jefferson harvest time the LIRR would be shipping up to 20 cars a day of potatoes and cauliflower. The Remz Feed building opposite the Port Jefferson train station would receive by rail large shipments of Purina Chow poultry feed.

In 1885 one of the few seasonal canning factories was built in Mattituck by Mr. William H. Hudson. He canned all types of crops such as tomatoes, squash, asparagus, and cauliflower. The factory would ship about 200,000 cans of asparagus each year. Nearby was also a pickle factory that would pickle different types of crops. On the East End a farmer could see market prices in both Boston and New York and ship west to NY or decide to ship to Greenport and then to ships heading northward to Boston. Another type of crop the LIRR was shipping was cranberries between 1870s to the 1930s from the Riverhead area until other states like Massachusetts and Wisconsin made this crop unprofitable.

A big boost to Long Island’s agriculture happened in 1905 when the LIRR operated 2 experimental farms in Suffolk County at first in Wading and then later in Medford. Under the leadership of LIRR president Ralph Peters these to farms grew every type of fruit, vegetable and flower in the mixed sandy soil known as the “pine barrens”. he experimental farms proved that desolate landscape could be made more productive under the proper course of cultivation. During the harvest time of 1905 the LIRR transported 437 tons of berries, 10,075 tons of cauliflower, 20,962 tons pf pickles, and 53,724 tons of potatoes. The LIRR used 3,250 freight car loads to haul the Long Island produce to market.[9]

LI Ducks

A very

important part of Suffolk County’s agriculture can be dated back to 1873 when 9

Peking ducks were brought to the United States. This type of duck grew faster

than other types of ducks and in about 4 months a Peking duck would be ready to

be processed for the market. Between 1880 and 1885 the duck farming industry

grew in the Speonk and Eastport area. By 1900 duck farming on Long Island was

well established with over 30 duck farms between the Moriches, Eastport and

Riverhead areas. The world’s largest duck farm until being destroyed by the

1938 Hurricane was the Atlantic Duck Farm located in Speonk which produced

125,000 ducks in 1916 and 260,000 ducks in 1938. After the Hurricane ½ of the farm was under

water. And then in Riverhead the duck

farm owned by Hollis Warner became the world’s largest with an annual

production of over 500,000 ducks. By

1940 there were over 90 duck farms in Suffolk County raising 60 % of the ducks in the United

States. And many of these duck farmers used the LIRR to ship to the New York

City market. After a duck was processed it along with up to 30 other ducks

would be packed into a barrel with chopped ice. The farmers would bring these

barrels trackside and the LIRR would then handle this high volume of express shipments.

The LIRR considered Speonk as a duck depot with so much shipping. In 1939 the

duck farming had a revenue of over $3 million. During World War Two more people

were introduced to eating duck due to the meat restrictions and this helped

market the product.

By the

mid 1940’s more trucks were being used to transport the ducks. At this time

more duck farmers were bringing their ducks to the Long Island Duck Growers

Cooperative Processing Plant in Eastport. Ducks would be killed and then flash

frozen solid and shipped by truck to market.

By the

mid 1940’s more trucks were being used to transport the ducks. At this time

more duck farmers were bringing their ducks to the Long Island Duck Growers

Cooperative Processing Plant in Eastport. Ducks would be killed and then flash

frozen solid and shipped by truck to market.

In 1959 the total annual production of duck reached a peak of 8 million. But duck farming created a lot of water pollution that effected the environment of Long Island such as shellfish. Between 1951 and 1968 several laws and regulations were enacted to treat the polluted waters.

In 1960 44 Long Island duck farmers formed a cooperative which would have a total of 5 million ducks to process each year. The farmers built 2 processing plants which were located in Eastport and Riverhead. The plants closed in 1987. Long Island’s last and largest duck farm is the Corwin Cresent Duck Farm located in Aquebogue. Since 1908 it has been expanding and upgrading. In the 1950’s a processing freezing facility was built on site. And in 1984 a modern feed milling operation was purchased. In the year 2000 a waste treatment facility was added. The farm process’s more than 1 million ducks a year and at any given time there is 140,000 ducks on the farm. The ducks are grown in indoor confinement, with no access to streams, and the pollution problem is less harmful.

The year 1910 was a milestone to the LIRR with Penn Station and the tunnels leading to them completed. Then in 1917 the Hell Gate Bridge was built which was significant in being able to connect the LIRR with the New Haven freight traffic. The Penn Station tunnels were very useful in giving access to dairy milk trains in the very early hours of the mornings. Photo: Bernstein's Duck Service, Center Moriches c.1950 Archive: Brad Kolodny

GLF Grain

Elevator and feed mixing plant in Riverhead NY was built in 1947. Robert Emery

photo, Robert Emery Collection, (courtesy of Stony Brook University).

In 1920 the New York State Grange, the Dairyman’s League, and State Farm Bureau combined to organize the Grange League Federation (GLF). It was a cooperative of farmers, that had a board of directors, managers and represent ivies from local committees and districts. A farmer would be able to purchase feed, seed, farm machinery, and fertilizer. As a shareholder in the GLF, at the end of a successful crop, receive a refund such as in stock feed, and fertilizers that were purchased during the last fiscal year ending June 30.

The GLF

duck and chicken feed mixing plant for bulk feed. Robert Emery photo, Robert

Emery Collection, (courtesy of Stony Brook University).

The GLF was one of the largest farm cooperatives in the United States. The GLF was headquarted in Ithaca NY and served 150,000 farmers in New York , New Jersey, And Pennsylvanian. The GLF directors were farmers that were elected by representatives from each farming community. They would name the general manager and hold him responsible for operations, set policies to guide management and control expenses by an annual budget. Through this system of committee representation and directors control, a farmer had a say on how the GLF was being run.

In 1932 Suffolk County’s duck farmers formed there first marketing cooperative and the same year the GLF started in Center Moriches to serve the duck industry. In 1936 the GLF opened an office in Riverhead, and another office in Southold the following year selling rye and seed potatoes.

The GLF warehouse was the center of Suffolk County’s duck and farm industry. The GLF supplied feed and farm machines to farmers throughout the county. A rail served GLF fertilizer warehouse was opened in Central Islip and another rail served GLF feed/seed warehouse was built in Huntington.

In 1947 the GLF built a 7 story tall grain elevator and feed mixing plant in Riverhead. The GLF mixed feed for 75% of the 5 million ducks on Eastern Long Island. The GLF feed plant was the only manufacture of duck feed pellets in the United States- perhaps in the World. Needless to say the LIRR hauled a lot of feed/seed and fertilizer to the GLF warehouses. In 1964 the GLF and Long Island Produce merged and then were bought by AGWAY which still has a location in Riverhead.

A very important food crop that was grown on Long Island is the potato. The history of the potato can be traced back to South America around Peru and Chile which the Indians were growing potatoes for centuries before the Spanish brought the potato back to Europe. Then the Irish were the first nation to grow the potato as a filed crop. In 1719 Scotch-Irish settlers in Londonderry New Hampshire were the first to grow potatoes in America. And later on some farmers on Long Island started growing the potato.

A new market for potatoes opened up in Suffolk County when the LIRR built out to Riverhead and Greenport. Within a few years the market price for potatoes doubled in price from .18 a bushel to .42 a bushel around 1850. During harvest time for the potato which is between August and October a farmer would dig up his potatoes, have them graded, sacked and then brought to a potato dealer which were located near the LIRR. The potatoes would be weighed and then dumped into a reefer. The LIRR would then haul the potatoes westbound to the NYC market. The potato farmer at this time had small fields with limited production and had to deal with problems such as the potato blight and getting good seed potatoes which would be planted in March.

In 1908 a few potato growers formed a stock corporation called the Long island Potato Exchange in Riverhead. The exchange loaded potatoes, handled fertilizer and other farm supplies through its warehouse. The company, due to poor management, went out of business in 1914. By the time America entered World War One many inventions to help the potato farmer were manufactured as well as more scientific approaches to agriculture with experimental farms (called stations) located on Long Island. The Suffolk County Farm Bureau was organized which helped farmers with the latest information on solving the problems of production and marketing. Most Long Island potato farmers bought seed potatoes from Maine but you had to wait out the growing season to see if it was good crop. The seed potato couldn’t freeze or be kept hot or it would be a very bad year for the farmer. The State of Maine has a tight control over the potato and therefore a little chance that a potato would have fungus. In 1915 a few farmers from Riverhead traveled north to look over potato fields and selected the best looking fields and have the seeds shipped to Riverhead in the fall. By 1921 the group formed a company named the Long Island Produce and Fertilizer Co. They built a warehouse next to the LIRR tracks in Riverhead just to store potato seeds.[10] Every March delivering potato seeds to dealers would be good business for the LIRR.

Potato

House, Robert Emery photo, Robert Emery Collection, (courtesy of Stony Brook

University).

By the 1920’s there were over 37 potato houses serving farmers by grading potatoes and packing them between Calverton and the North and South Fork. Some of these efficient dealers and packers were Fanning and Housner, Maxim Bobinski, I.M. Young, Long Island Potato, Grange League Federation, A&P Produce, Suffolk Produce, Long Island Produce, South Shore Produce. These companies had many different trackside locations in just about every East End town. It would be up to a farmer who was watching market prices to decide when to bring his potatoes to any of the dealers. Some potatoes, depending on the market price, would be stored throughout the winter and spring to get the highest price. The potato houses were like warehouses equipped with fans and ventilating system and humidity and heating equipment. Between 1920 and 1940 the LIRR added new sidings to accommodate many newly built potato houses in Eastern Long Island such as in 1922 LI Produce in Riverhead. And in 1924 I.M. Young built a Calverton Potato House and another one in Riverhead. In 1926 the L.I. Produce completed a fertilizer warehouse in Mattituck. And in 1946 I.M.Young established themselves in Bridgehampton with a potato house. These as well as all the other potato houses were all shipping points for the LIRR. In 1929 the LIRR transported 11,000 carloads of potatoes. And in 1930 10,195 carloads of potatoes were handled by the rail road. This was the beginning of more truck completion for the LIRR. And big change that helped farmers everywhere with production during the dry years was the use of portable overhead irrigation.

At various times during the Summer and Fall harvest time the LIRR would station extra locomotives in Riverhead just to do the switch work at the many sidings in order to keep the regular road freights from spending too much time in Riverhead. During the 1930’s Diesel No. 401 or 402 was used. During World War Two a class H6sb 300 was used. Riverhead was also a turning point for “Cauliflower Specials” and “Potato Specials” at times. During the 1930’s it was common to see freight trains with 110 cars of potato reefers being hauled by the LIRR and mixed freight trains with 70 cars on them.

Between 1943 and 1947 the United States Government purchased practically all of Long Island’s crops and shipped them all by the LIRR . The freight traffic was so heavy that the LIRR had to use regular boxcars along with reefers to haul potatoes and cauliflower westward to Holban yard and points beyond. The freight business was so good that the LIRR had 36 freight stations repainted and 30 miles of new rail as well as new ties and ballast installed in 1943.

One of the problems that a potato farmer had to be concerned with was being affected by the golden nematodes. In 1941 a potato field in Nassau County the nematodes was discovered. It is believed that a US Army World War One surplus tire that were brought back to the United States from Germany was carrying this parasite along with dirt in its treads. It is resistant to chemicals and can remain dormant in the soil for many years. The nematodes will eat away at the roots of the potato and once found in the soil you will not be able to grow any more potatoes. This potato filed was purchased by Mr. Levitt and became Levittown. The golden nematodes is the reason why you are not allowed to export off Long Island any topsoil, sod, or bring into Maine any Long Island potatoes.[11]

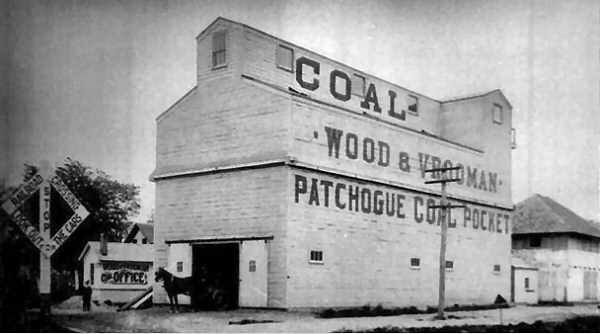

Coal

One of the most important commodity handled by the LIRR was anthracite coal. Up to the mid 1950’s just about every town had at least one coal dealer with track side facilities. There were over 34 coal yards on the Port Jefferson Branch and east of Riverhead on both North and South Forks receiving coal from the LIRR. In 1931 coal was 50 % of the LIRR freight traffic. But in 1934 coal traffic decreased to 45% of the total tonnage of freight hauled that year. Coal in 1941 earned the LIRR 16 % of total revenue of $ 1,457,474.[12] The LIRR served the State Mental Institutions that were very large coal customers receiving Bituminous coal. Kings Park State Hospital had a 19 car capacity coal trestle for its power plant that was built in 1940. Soft coal was delivered here until being closed in the late 1980s. Brentwood’s Pilgrim State Hospital received coal until being closed also. The Lace Mill in Patchogue received coal along with shipping and receiving goods from its rail siding until being closed in 1954. The Lace Mill was the largest employer in Patchogue which made curtains, handkerchiefs, and table cloths (the mill made parachutes during World War Two). The Baily Lumber Mill also in Patchogue which in 1892 had over 400 people working there made ship timbers, windows and trim. In 1941 Patchogue had 2 freight trains each day, one heading eastbound and another heading westbound. Because of these 2 mills Patchogue was called the “Mill Town”. The LIRR removed the Lace Mill rail siding in 1965. LILCO was also a very large customer of coal, and owned a catalytic gas storage plant located in Riverhead that was built in 1949 which had coal delivered there.

By the

mid 1940’s the use of natural gas and home heating oil caused the decline of

coal traffic for the LIRR. Trucks could bring in fuel oil to the many oil

dealers on Long island and bulk oil would be shipped along with other types of

commodities such crushed stone ,sand and gravel on boats and barges. In a lot

of Long Island towns many coal dealers closed by the 1950’s and the LIRR would

remove its rail sidings.

Situated

alongside the LIRR tracks at the crossing of Potter Avenue is the interesting

coal silo of the Wood & Vrooman Patchogue Coal Pocket and adjacent lumber

yard. View is looking SW c. 1910. For many years a landmark trackside, the

building was destroyed by fire on May 6, 1964.

Another common industry which appeared in every town was the lumber yards. The LIRR would set out and pick up box cars that were loaded and unload lumber by hand, stack by stack, before the days of the fork lift. As towns on Long Island grew ,along with the population, a need for building supplies were in demand. A few companies making bricks were located in Suffolk: one was in Southold named C.L. Sanford Brick Yard which had a 4 car siding. The Sage Brick Company was located in Greenport and the Long Island and Fire Island Brick Co. was located in Sag Harbor. These local manufactures would hand stack box cars with bricks. These companies closed down by the Great Depression due to a bad economy and little construction being done.

In between the 1920’s and the 1930’s it is interesting to know that the LIRR owned 2500 revenue freight cars, at least half of these were box cars to help serve the lumber yards ,delivering new automobiles in box cars, new tractors on flatcars, transporting milk, hauling feed and seed and other merchandise freight. The LIRR shipped countless telephone poles and cable to LILCO and New York Telephone owned sidings all over Suffolk County. LILCO had sidings in Babylon, Southampton, Greenlawn, Port Jefferson, Brentwood, and Riverhead. New York Telephone had sidings in Bay Shore, Patchogue, Southampton, and Riverhead. It was here that telephone poles would be delivered and known as pole yards since the telephone poles would be stacked on each other. Also thousands of miles of reels of electrical and telephone cable were delivered.

Milk Car # 3000 Builders Photo Archive: Steven Lynch,

(courtesy of Steven

Lynch,www.trainsarefun.com).

Riverhead view W at

Osborne Ave. Crossing-Golding’s Feed and Lumber Yard siding c. 1962 Brad

Phillips (Courtesy of Steven Lynch, www.trainsarefun.com).

M. Remz Bros.Feed (after 1931,as per Emery map), view S 1978 Photo Steve Lynch

The LIRR freight traffic was so different from other major railroads. The LIRR was the only rail road in the United States that was getting more revenue from passenger service than from freight service. Also the LIRR is a terminal rail road and not a line that could easily connect freight with other railroads due to the major restrictions such as the low clearances of bridges and tunnels. And since being surrounded by water with only having freight leaving westbound by either the Hell Gate Bridge or using the car floats at Bay Ridge and Long Island City. The LIRR freight movements was short haul and the LIRR was forced to perform an excessive amount of movements in order to get freight cars from the East End of Long Island to the rest of the United States. And only a small percentage of freight traffic came from Long Island with the majority of freight coming into Long Island. There would always be a large number of empty freight cars leaving westwards, during the 1930’s this was about 50%.

LIRR records show that approximately 600 loaded cars were received by the LIRR each day in 1941. The LIRR freight customers could load about 200 or about 1/3 of these cars during the same period. Since the LIRR could easily obtain empty cars for loading it wasn’t necessary to own a fleet of freight cars. In 1940 the LIRR freight revenue was $7,700,000. Since 1921 the LIRR freight service had earned from 1/4 to 1/3 of revenue every year-and that includes the Great Depression years. But truck competition was causing the LIRR to loose freight traffic.[13] For example in 1930 there were 10,195 car loads of potatoes moved by the LIRR, but in 1939 there was only 325 cars loaded with potatoes.

In 1940 there were 465 truck companies hauling freight both to and from Long Island that is estimated to be1/2 of freight tonnage handled by the LIRR. One of the prime causes of the LIRR financial decline was the increased use of trucks, instead of the LIRR, to haul freight. The trucks offered faster time than freight trains, and the service could be done at a lower cost. For a new industry to open and operate you wouldn’t need a rail spur. Also trucks, as well as the roads and highways, were improving which made trucks more efficient and flexible. Up to this time period the LIRR freight hauling was making a profit but things started to go from bad to worse. In 1948 the railroad lost 25% of the freight business and yet was still creating new business such as building a new rail siding in Greenlawn for a warehouse owned by Republic Aviation Co. in 1948. And the LIRR in 1953 built a new siding for the Grumman Corp in Calverton.

The 1950’s saw alot of changes to the LIRR. Besides being bankrupt, the rapid decline of profits from freight was effecting the LIRR. In 1901 the LIRR made $1,381,453 in freight revenue. And in 1927 the LIRR freight revenue was $11,856,835. In 1929 the revenue was $9,500,000 at the start of the Great Depression. The operating revenue from freight traffic for the LIRR in 1933 was $5,769,000. The LIRR earned $7,700,000 in freight revenue in 1940. With the building boom on Long Island in 1953 contributing 25% of freight revenue the LIRR made $6,000,000. In 1954 the freight traffic for the LIRR contributed 1/3 revenue for a total amount of revenue of $12,994,106.

The New York State Public Service Commission in 1958 allowed the LIRR to eliminate 14 LIRR express and freight stations that handled less than carload freight (LCL). In 1954 alone the LCL freight wasy 18% of total freight movements for the LIRR but the trucking industry dominated the market. Also in 1958 the LIRR slashed freight rates for potatoes being shipped by 50% to compete with trucks. This came to a reduction in price from $93.60 to $50 a car load. At the time nearly all the potatoes grown on Long island was moved by truck to the market.

The early 1960’s the LIRR was kept busy by tearing down express offices and express stations, as well as a few freight stations. In 1964 the LIRR moved 2500 freight cars of seed potatoes as it had been doing each year. In 1966 there were a total of only 114,000 car loads of freight moved by the LIRR which meant a loss of traffic valued at $5 million. In 1967 the LIRR lost $6 million in lost freight traffic and the figure lost in 1968 was $7 million. By 1969 the LIRR saw a loss of $8.5 million. In 1970 the LIRR hit the $10 million mark in lost revenue to trucks, there were only 283 farmers growing potatoes that year in Suffolk. And the loss revenue for 1971 was a total of $ 11 million. With the takeover of the MTA the LIRR freight traffic just dropped year by year. For example in 1975 there was only 60,000 car loads moved. And in 1977 54,000 car loads of freight was handled by the LIRR. The dollar amount of lost freight business amounted to $2,348,733 in 1962 but by 1975 it lost $15 million in freight handling. In 1973 with Suffolk County’s agricultural industry figured at value of $71 million trucks were moving 85% of the freight. The freight traffic for the LIRR dropped by 42% since 1965 and the MTA lost $14 million in 1972. The LIRR moved 180,000 tons of fertilizer and duck feed in 1973 but the trucks moved 500,000 tons of produce from Suffolk. The potato farmers by this time were receiving seed potatoes shipped from Maine by truck right to their farms. By 1979 the LIRR freight service which has been declining for over 15 years was losing more than $20 million a year with a peak reached in 1975 at $22.2 million. The MTA was receiving subsidies from New York State to cover these amounts. Trucks were moving 90% of freight into and out of Long Island at this time.

Each year the LIRR was losing more freight business. It hauled 6,152 cars less in 1977 than in 1976 and in 1981 8,255 cars less was shipped by the LIRR than in 1980. The difference between 1984 and 1986 was 2,543 lesser freight cars shipped. In 1984 Suffolk County had the highest total value of farm receipts of any county in New York State. And Suffolk County is the 2nd most populated county in New York State outside of New York City. The major crops grown in Suffolk are potatoes, vegetables, floriculture, sod, nurseries, fruit and ducks at this time. The LIRR only moved 5% of freight in 1984 which was 20,002 freight cars. By 1987 there was only 17,131 freight cars moved. The LIRR freight department only had 8 freight engineers working 10 to 12 hours a day.

The LIRR had eliminated its freight service in 1997 by contacting this service to the New York & Atlantic Railroad and is now completely focused on moving people into and out of New York City and across Long Island. By this time only 3% of freight traffic was handled by the LIRR.

C420 # 229,

MP15AC # 155, LIRR C55 King’s Park 06/10/1985

Credits

Steven Lynch www.trainsarefun.com

Benton Roueche, the Delectable Mountains

Nathaniel A. Talmage, The Growth of Agriculture in Riverhead Town. Suffolk County Historical Society, 1977

J.G. White Engineering Corp of N.Y., The LIRR its Problems and Future: a summary of a study. J.G. White Engineering Corp., 1942

Molly Schoen, East Northport an incomplete history. Rotary Club of East Northport, 1998

Suffolk Agway Coop, Inc. golden anniversary 1932-1982. Suffolk Agway 1982

Historical Newspapers of Long Island

Suffolk County Libraries

Long Island Maritime Museum

Robby Hartmann, Oral Interview Long Island Cauliflower Association

Don Fisher, Riverhead Museum of Long Island

Thomas R. Bayles, Farm Fish Crops

Robert M. Emery LIRR Collection @ SUNY Stony Brook N.Y.

Eugene S. Griffing, Trap Fishing 1860-1950

Amy Gernen, Long island Oyster

Rowon Jacobsen Edible East End Aug.2008

Ralph Gabriel, The Evolution of Long Island

Edith Fullerton, The Lure of the Land. Long Island Railroad Co., 1911

Mark Kurlenski, The Big Oyster

John Holzapfel, Oysters

Geoffrey K. Fleming and Amy Folk, Munnawhatteaug The Last day of the Menhaden Industry on Eastern Long Island. Southold Historical Society 2011

Steve Clarke Greenport Yacht and Shipbuilding Company Oral Interview

Northport Historical Society

Fred Kramer, Long Island Rail Road. Carstens Publications, 1986

Oysterponds Historical Society

Vincent F. Seyfried, The Long Island Rail Road, a Comprehensive history Part Six: The Golden Age 1881-1900

Joe Geryela Long Island Farm Bureau Oral Interview

Carl Darenberg Montauk Marine Basin Oral Interview

Bill Sanok Mattitcuk Oral Interview

Mildred H. Smith Early History Of The Long Island Rail Road, 1834-1900. Salisbury Printers,1958

[1] Interview with Don Fisher.

[2] Interview with Bill Sanok

[3] Geoffrey K. Fleming and Amy Folk, The Last days of the Menhaden Industry on Eastern Long Island. Southold Historical Society 2011.

[4] Ibid ,Fleming and Folk

[5] Interview with Steve Clarke

[6] Interview with Robby Hartmann.

[7] Talmage, Nathaniel A., The growth of agriculture in Riverhead town, Suffolk County, New York Suffolk County Historical Society, 1977.

[8] Molly Schoen, East Northport incomplete history, Rotary Club of East Northport, 1998.

[9] Edith Fullerton, The Lure of the Land, Long Island Railroad Corp, 1911.

[10] Op. cit, Talmage

[11] Interview with Joe Geryela

[12] J.G. White Engineering Corp of N.Y., The LIRR its problems and future: a summary of a study, J.G. White Engineering Corp, 1942.

[13] Ibid,White.