THE LONG ISLAND HISTORICAL JOURNAL

The LIHJ Fall 2004/Spring 2005 Volume 17, Nos. 1-2

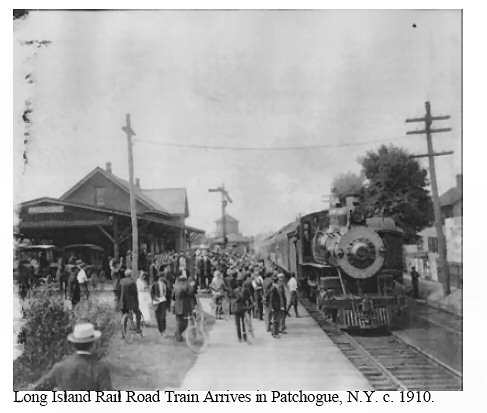

Cover: First Long Island Rail Road train from Penn Station to arrive at Patchogue, September 8, 1910. Courtesy of the Queens Borough Public

Library, Long Island Division, Howard Conklin Collection.

THE LONG ISLAND RAIL ROAD AND IT’S PROMOTION OF LONG ISLAND, 1900-1930

by Sean Kass

Standard histories of Long Island describe the region’s suburbanization as a post-World War II phenomena, ignoring significant suburbanization that took place before that era. Sean Kass explores the growth of Long

Island as a tourist destination, an agricultural haven and, finally, a residential enclave in the years 1900-1930. Mr. Kass finds that urban development patterns are not only influenced by available modes of

transportation, but often by the aggressive marketing of new transportation technologies as well.

Nineteenth century Long Island was predominantly rural. Agriculture and maritime activities, the two main areas of employment, sustained Long Island’s small towns and villages. With the exception of a significant sand mining industry and a number of large hotels along the shores, there was little development to speak of. Yet, by the latter part of the twentieth century, Long Island was home to a population of 6.8 million and the nation’s busiest commuter railroad. Furthermore, it acquired a reputation as the quintessential American suburb.

While the process of suburbanization is often thought to have been a post-World War II phenomenon, a first wave of suburbanization occurred on Long Island during the first three decades of the twentieth century. From 1900 to 1930, the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) promoted the transformation of Long Island from a rural expanse to an area of elite leisure. In pursuit of riders, the railroad marketed Long Island as both a recreational paradise for sojourners and a year-round haven for the growing numbers of potential commuters.1

The Early History of the Long Island Rail Road

Yale historian Ralph Henry Gabriel observed in 1921 that railroad service “did not come to Long Island primarily for the sake of the Island itself.” Rather, the LIRR was founded in 1834 for the purpose of carrying urban residents from New York City to Boston (and vice versa). The plan was to connect passengers traveling from New York with Connecticut via the train to Greenport, Long Island. There they would board a ferry to Stonington,

Connecticut, where they would board another train that would take them the rest of the way to Boston. To achieve this the New York State Legislature chartered the Long Island Rail Road in 1834. The Long Island through-route, completed in 1844, cut five hours off the fastest all-land route to Boston. From 1844 to 1848, the Long

Long Island Rail Road through-route was the principal passenger and mail route between New York and Boston.2

Profits from the Boston through-route did not peter out or gradually decline - they stopped dead. With the

establishment of a railroad through Southern Connecticut in 1848 it was cheaper and faster to travel from New York to Boston solely by rail. The role of the LIRR as part of the route to Boston was defunct, and the railroad was forced to reformulate itself as a local railroad. Over the next thirty years, the LIRR expanded rapidly in an effort to serve more Long Island communities.3

In 1863, the Long Island Rail Road was taken over by two prominent New York City politicians: Oliver Charlick and former New York City mayor William Havemeyer. During the tenure of President Charlick (1863-1875), the railroad lost money for twelve consecutive years. Conrad Poppenhusen eventually succeeded Charlick.4 Poppenhusen was the owner of the Island’s two other major railroads: the South Side Railroad and the Flushing, North Shore, and Central Railroad. When he became President of the LIRR, Poppenhusen consolidated his railroad empire into the LIRR system. This event marked the end of decades of fierce competition and rate wars between Long Island’s rival railroads. Nevertheless, the financial difficult ies of maintaining an enormous infrastructure with low ridership forced the LIRR into receivership in 1877.5

The Resort Industry on Long Island

Nothing about Long Island’s development was spontaneous. It was a premeditated transformation orchestrated by a number of individuals and groups with land or business interests on the Island. Indeed, the story of Long Island suburbanization in the early twentieth century is largely one of successful promotion. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, the builders and owners of Long Island shorefront real estate began to promote the Island as a vacation destination. A series of massive hotels were constructed along Long Island’s shores. In order to cultivate an infant tourist industry, those invested in Long Island promoted the area as a recreational paradise. These seaside resorts attracted thousands of weekend visitors from New York City. This resort phenomenon persisted into the early twentieth century. The development of hotels, businesses, and small towns formed a vital first step in Long Island’s suburbanization as tourist destinations soon became seasonal resort villages and later year-round suburban neighborhoods.6

The idea of a resort industry had originally evolved under Colonel Thomas R. Sharp, the Long Island railroad’s receiver and president from October 1877 to December 1880. Forced to deal with the financial problems bequeathed by the Charlick and Poppenhusen administrations, Colonel Sharp attempted to increase both freight and passenger revenue.

At the time, the railroad owed a total of $14,190,000 in debt and loans. On the freight side, Sharp offered discounted rates and special trains to Long Island farmers and fishermen. These special freight trains would stop on request between stations in order to load produce. In addition, the return transport of produce containers was free.

With respect to passenger service, Sharp hoped to raise revenue by promoting tourism. He instituted excursion trains to Fire Island, Babylon, Patchogue, and the Rockaways. Excursion trains offered daily round trips to these burgeoning resort locales. In addition to the excursion trains, the Evening Bathing Train ran from Jamaica Station to

Rockaway Beach during the summer nights of 1878 and 1879. Colonel Sharp purchased state of the art Pullman cars for Rockaway Beach and insisted that they be drawn by the newest locomotives, which were faster and less smoky. Finally, Sharp provided extra service during popular vacation weekends.

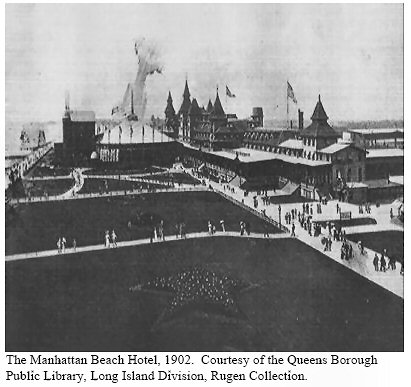

While Sharp attempted to cultivate the nascent tourist industry, the resort era on Long Island became a reality at the hands of Austin Corbin, LIRR President from 1881 to 1896. During the 1870s, Corbin personally built and operated several of the largest and most luxurious of the seaside resorts: the Manhattan Beach Hotel, the Oriental Hotel, and the Argyle

Hotel. In 1885, he added the Long Beach Hotel to his real estate empire by buying out Colonel Sharp and his associates. By that time, Corbin owned four major hotels on Long Island’s seashore - each of which could accommodate several hundred guests, and had invested in several others. He used the LIRR to secure his investment in the budding Long Island

tourist industry. In 1888, advancing tidewaters had washed up to the foundations of the Brighton Beach Hotel, another one of the resorts in which Austin Corbin had a personal financial stake. He arranged for the railroad to rescue the endangered landmark hotel. Under his instructions, the entire hotel was placed on flatcars and moved 200 yards inland.7

Under President Corbin, the railroad actively promoted the hotels on Long Island. Corbin hoped these efforts would simultaneously promote his properties and save the troubled railroad he had taken over. With his guidance, the LIRR became “the principal publicist of the area’s resort potential.” The railroad began producing a series of promotional

publications, including annual visitor’s guides. Above all, these guides almost always included an extensive list of the boarding houses and hotels in each area. They extolled Long Island as the ideal spot for a summer getaway. The seaside hotels provided countless havens “to which the tired dweller of the city may betake himself for rest, recreation, and recuperation.”8

The Manhattan Beach Hotel, 1902. Courtesy of the Queens Borough Public Library, Long Island Division, Rugen Collection.

Besides being the builder and promoter of the resort boom of the late nineteenth century, the LIRR was also the primary means of transportation. As one of the annual visitor’s guides claimed, “every important place on Long Island is reached quickly and comfortably” via the Long Island Rail Road. This too was Corbin’s work. As noted earlier, Corbin had begun constructing hotels several years before becoming president of the LIRR. It was during these years that he realized that efficient rail transportation could open up new areas of Long Island for the summer resort business while rescuing the railroad from its financial straits. While President, Corbin secured adequate rail service for all of Long Island’s major resorts. As Robert B. MacKay has noted, “many of the large resorts had their own railroad depots since convenient transportation links were . . . the key to success.” In an age before the motor vehicle was widely available for either public or private

transportation, the railroad provided the most efficient means of travel to and from Long Island’s resort hotels. The LIRR gave Long Island a privileged position as the summer bathing area for the man of affairs (and his family) who wished to relax without losing contact with developments in the city and at the office.9

The success of Corbin’s efforts was evident in the sheer scale of the resort industry during his term as president (1880-1896). By 1895, the railroad’s total number of riders (13,768,163) was more than four times that of 1877 (3,063,041). Largely thanks to Corbin, Long Island had become the home of some of the largest hotels in the world. The railroad visitor’s guides reported that Long Island had accommodations for over 24,000 vacationers. In the span of twenty years, Corbin and the Long Island Rail Road had built, promoted, and provided transportation to a substantial resort industry on Long Island. The recreational iconography established by the emergence of the resort industry in the late nineteenth century provided much of the impetus for families to move to Long Island in the early decades of the twentieth century.10

Recreation and Promotion

Publicizing these recreational possibilities was the job of the LIRR’s Passenger Department. Its steady stream of promotional publications reached thousands of homes, clubs, and businesses. The department’s broad objective was to cultivate “increased enthusiasm and love for Long Island.” From 1895 to 1930, the Traffic and Passenger Department of the LIRR issued an average of over two publications each year. These publications were predominantly pamphlets that ranged from seventeen to over two hundred pages and almost always included a large number of photographs. These were generally distributed free of charge upon application by mail or at one of the LIRR’s New York City terminals.11

The railroad’s publications served two aims. First, they were intended to advertise Long Island’s potential as a resort. In the 1903 edition of Long Island Illustrated, for example, a substantial majority of the photographs are of hotels and inns at various locations on Long Island. In addition to the more than twenty-five photographs of hotels, the pamphlet contains “a list of boarding houses and hotels in each locality” and the recreational opportunities they offered. Second, the railroad publications tried to attract permanent residents to Long Island. Suburban Long Island, “The Sunrise Homeland” (1921),

for example, was published “to promote the advantages of Long Island for suburban living.”12

The following table presents a partial list of the publications issued by the railroad between 1895 and 1930:13

Table 1

Beauties of Long Island 1895

Long Island Summer Resorts 1895-1900, 1902-1904

Cyclists’ Paradise 1897, 1898

Long Island Illustrated 1897, 1898, 1900, 1901, 1903, 1905,

1908

Unique Long Island 1898-1904 (issued annually)

Summer Resorts on Long Island 1898, 1908

Summer Homes 1901

Long Island Resorts 1909, 1912

Diamond Jubilee of Long Island

Railroad Company 1910

Long Island: Where Cooling Breezes Blow 1913

Long Island Agronomist 1914

Long Island and Real Life 1915, 1916

A Statement of Facts 1920

LIRR Information Bulletin 1920-1931 (issued annually)

Long Island, America’s Sunrise Land 1921-1932

What Poets Say About Long Island 1923

Campaign of Education and Good Will 1928

Even this large number of publications does not encompass the extent of the railroad’s promotional efforts. The railroad spent considerable sums of money advertising in area newspapers and periodicals. Some of the promotional publications, including Campaign of Education and Good Will listed in the table above, were actually compilations of

advertisements that had been published elsewhere. In addition, the railroad organized and hosted promotional events. LIRR Special Agent Hal B. Fullerton, the single most important figure in the railroad’s massive promotional campaign, spent thirty years in the railroad’s Passenger Department “promoting and advertising events, activities, or plans that would bring public attention to the Island’s potential for sport, recreation, business and residential development for both the middle classes and the urban elite.” These events included lectures delivered by Fullerton (1897-1929), the Vanderbilt Cup automobile races (1904-1910), the Mile-A-Minute Murphy Challenge (1899), and experimental farms at Wading River (1905-1910) and Medford (1910-1927).14

The LIRR advertised many recreational opportunities on Long Island, but the sea was always chief among them. It was the beach that had precipitated the resort boom, and it dominated all promotional efforts. During the summer months, visitors thronged to Long Island’s beaches and bathing pavilions. Summer bathing was “a great magnet.”

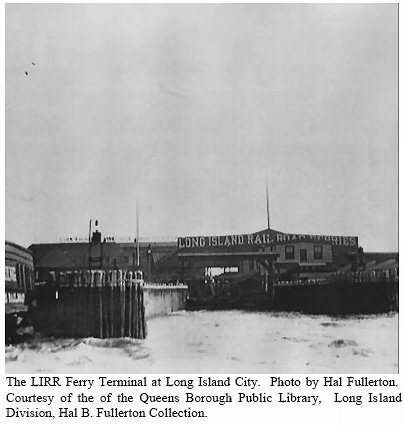

The LIRR Ferry Terminal at Long Island City. Photo by Hal Fullerton. Courtesy of the of the Queens Borough Public Library, Long Island Division, Hal B. Fullerton Collection.

Boating was an attraction for many. Popular yacht clubs emerged at various locations along Long Island’s shores. Even on dry land, Long Islanders could enjoy “Cool Breezes from off the Sea!” The LIRR’s promotional pamphlets almost always had an illustration of the sea on the cover. The 1921 issue of Long Island, “The Sunrise Homeland,” for example, had a picture of two young girls holding hands on the beach. In like manner, the cover of the 1928 issue showed three young women sailing a yacht. When people thought about the Sunrise Homeland for a vacation or a home, it was clear that “in no particular is there greater attraction than its seashore.”15

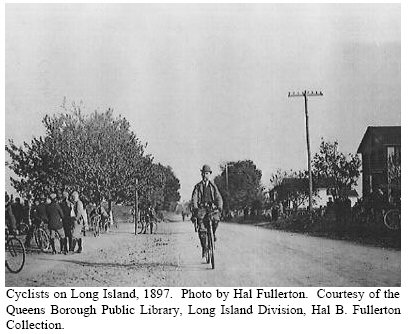

Long Island was not only surrounded by usable waters; much of it was also flat. That geographic feature provided the perfect terrain for an increasingly popular activity – cycling. By the late nineteenth century, Long Island had become a fashionable gathering point for cyclists. A number of advances in cycling technology, including inflatable tires and

the rear-wheel-driven bicycle, resulted in a national surge in cycling, and Long Island was a center of the new craze. The Island was ideal for bicyclists because it offered pleasant roads through wooded areas as well as seashore trails. Bicycle clubs were formed “in practically every village on the Island.” In 1896, there were forty-seven cycling associations in

Brooklyn alone.

Major cycling organizations such as the League of American Wheelman (LAW) and the Good Roads Association were also active on the Island. Hal Fullerton was active in both organizations. He served as Second Vice President of the Good Roads Association’s Brooklyn chapter and was elected to both the state board and the national assembly of LAW as a delegate from the second district of New York (Long Island). In fact, his involvement in these organizations and his reputation as a proponent of cyclists’ interests was one of the main reasons he was recruited by LIRR President William Baldwin. After

being hired by the railroad in 1897, Fullerton immediately set about the promotion of Long Island as a prime area for cyclists. He equipped LIRR passenger cars with LAW-approved bicycle racks. He later improved these

combined passenger and bicycle cars (and obtained a patent for his design). In 1897, Special Agent Fullerton published Cyclists’ Paradise from the railroad publication office. The booklet detailed a number of recommended bicycling routes on Long Island. The original 10,000 copies were quickly exhausted, and the pamphlet went through at least two additional editions. In the summer of 1898 alone, the LIRR transported 150,000 bicyclists to points on Long Island.16

By far the most imaginative of the LIRR’s efforts to promote bicycling on Long Island was the Mile-a-Minute Murphy Challenge. During the summer of 1899, Charles M. Murphy, a champion amateur cycle racer from Brooklyn, thought that in the absence of wind resistance he could he ride a mile in one minute or less. Together, he and Fullerton designed a wood-planked raceway that would run between the railroad tracks of the LIRR’s central line near Farmingdale. Theyattached a wind-protective hood to the rear of a railroad car: this car would serve as Murphy’s pace car, clearing the air in front so that he could ride unencumbered by air resistance. Murphy’s Challenge was highly publicized by the Passenger Department. They documented his training regiment and invited every possible media outlet to the event. Although none of his test runs had been successful, Murphy did ride one mile in 57.8 seconds during the actual challenge run. “Mile-a-Minute” became an international celebrity, and Long Island gained valuable publicity as a prime location for cycling.17

While cyclists rode by, New York City’s wealthiest citizens built massive country estates along the North Shore. As Eugene Armbruster noted in 1914, “many men of great means have acquired large tracts on Long Island for their country homes.” Between 1900 and 1918, 325 mansions (houses of twenty-five rooms or more) were constructed on Long Island. By 1930 there were more than 900 mansions on Long Island. The wealthiest American families -the

Morgans, Goulds, Chryslers, Fords, Pratts, Vanderbilts, and Guggenheims – and many of the most famous individuals – Conde Nast, Ralph Pulitzer, William Randolph Hearst, Nelson Doubleday, Sinclair Lewis, Thomas Edison, Payne Whitney, Theodore Roosevelt, and Louis Comfort Tiffany - owned large homes on Long Island. Together their estates formed Long Island’s “Gold Coast” and provided the setting for F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel The Great Gatsby (1925). Much as Fitzgerald had described them, the Gold Cost mansions formed a pleasure land “in which millionaires and celebrities . . . danced the night away.”18

While the Gold Coast parties were an attraction, Long Island appealed to New York City millionaires for the same reason it had appealed to summer vacationers and to the new middle class residents: outdoor recreation. Long Island was seen as “one of the most ideal summer breathing places on the American continent.” For the upper classes, the Long Island recreational experience was centered on the country club. The country club offered opportunities for such popular activities as golf, tennis, polo, yachting, and fox hunting. The club became “the focus of suburban social life” and induced many of

New York’s elite to build estate homes on Long Island. For example, in the thirty-five years following the construction of the Seawanhaka Corinthian Yacht Club’s waterfront facility at Oyster Bay, the club’s members built over forty mansions in the area.19

Other popular activities included golf, tennis, and polo. In 1900, Long Island Illustrated advertised that forty golf courses were located on Long Island. By 1930, there were an additional forty-eight golf courses built on Long Island. Long Island was also home to the country’s largest tennis club at Forest Hills. The West Side Tennis club relocated to Forrest Hills in 1912. Its new facility included the world’s largest tennis stadium, which served as the site of the U.S. Open from

1923-1978.20

Polo fields could be found at many of Long Island’s country clubs, including Piping Rock, Montauk Beach, Meadowbrook, Rockaway Hunt, and others. The sport gained such popularity on Long Island that a 40,000-seat stadium was built exclusively for polo. Every American to play in international competition against Britain between 1886 and 1939 hailed from Long Island. Based on these factors, the LIRR marketed Long Island as “the American Home of polo.” Nearly all of the great country estates erected in the area of Old Westbury and North Hills were built so that aspiring polo players would have adequate living quarters while they honed their craft on the polo grounds of the nearby Meadowbrook Club. Hence, by the year 1900 “sporting interests determined the building sites of mansions.”21

The Brighton Beach Hotel, 1917. Courtesy of the Queens Borough, Public Library, Long Island Division, Postcard Collection.

Finally, the railroad promoted the agricultural opportunities on Long Island. These efforts focused on Suffolk County and were intended to increase the railroad’s freight business. In 1903, the railroad reported that Long Island was “admirably adapted to flower, vegetable, and fruit culture and thousands of its broad acres are being scientifically and intelligently tilled.” Similarly, an article that appeared in the South Side Messenger in 1911 juxtaposed a report on the thousands of acres being

successfully farmed with the claim that Suffolk County could still provide small rooms and country houses for an additional 200,000 people. Nevertheless, LIRR President Ralph Peters believed there was a difference between word and action. He thought that if the railroad really expected people to move to Long Island in order to farm, he would have to demonstrate that it could be done. To this end, he created an Agricultural Department of the railroad, headed by Special Agent Fullerton. He instructed Fullerton and his wife, Edith, to find ten of the worst acres in Suffolk County and proceed to farm them. The results would then be published in area newspapers and promotional publications for the sake of demonstrating “that others may do likewise, or even exceed the results in the same brief space of time.” It was hoped that this campaign would bring farmers to Suffolk Country and freight revenues to the Long Island Rail Road.22

Thus, Long Island had become the “cradle of many of America’s nascent

recreational pursuits.” As such, it could attract both summer

and permanent residents from among the middle and upper

classes. Vacationers began to put down roots and build summer homes.

This was especially true along the South shore, which saw the

greatest amount of real estate activity. Even Suffolk County, Long

Island’s easternmost county, saw modest increases in population as

farmers embraced the example set by the railroad’s experimental

farms.23

Pennsylvania Station and the East River

Tunnels

The railroad’s infrastructure was equally as important as

its promotional efforts to the development of Long Island during this

period. Most significant was the construction of Pennsylvania Station

and the East River Tunnels. Prior to the opening of the tunnels in

1910, Manhattan-bound passengers had to take a ferry across the East

River or endure multiple train transfers. The tunnels provided a long

awaited direct rail route that was faster and more convenient than

either of the previous alternatives. Easier and more efficient

transportation options greatly increased the number of commuters who

chose to make Long Island their home. By bringing New York City and

Long Island closer together, the direct rail route sired a population

and home building boom on Long Island.24

As the LIRR system’s shape matured in the late nineteenth

century, the railroad could no longer count on expansion to increase

ridership. To increase traffic, the LIRR began a new promotional

campaign: commutation. It published “booklets setting forth the

advantages of every little town.” The railroad recognized that

commutation had enormous revenue potential. If it could convince a

critical mass of people to become suburban commuters, the LIRR would

see a sizeable increase in the number of daily riders. Thus,

beginning in the 1870s, the LIRR Passenger Department tried to

convince potential Long Island homeowners that daily commutation to

New York City was manageable.

The earliest commuters to Manhattan were Brooklyn residents who took

ferries across the East River. The LIRR sought to make commutation an

attractive possibility for residents further east. As with nearly all

of the LIRR’s promotional activities during this period,

Special Agent Fullerton was intimately involved. In an 1898

promotional pamphlet called Unique Long Island, Fullerton enumerated

that the homes of Long Island were within quick-and-easy reach of the

city. He also discussed the new railroad improvements and in

particular the express trains, which brought “every section of the

Island within easy

reach of Greater New York.” These comments were echoed

almost verbatim in the 1900 edition of Long Island Illustrated. In

both cases, they were targeted at the prospective commuter.25

The railroad’s effort to promote commutation met with

moderate success between 1880 and 1910. During the 1880s, the LIRR

ran fifteen trains daily along the main line and twelve along the

South Shore Division -and a few commuter towns were emerging along

the railroad routes. During the 1890s, the number of Long Island

commuters increased substantially: the Main Line, South Shore

Division, and Oyster Bay Branch of the LIRR all saw 50 percent

increases in the number of daily commuter trains.26

Cyclists on Long Island, 1897. Photo

by Hal Fullerton. Courtesy of the Queens Borough Public Library, Long

Island Division, Hal B. Fullerton Collection.

Despite this growth, the number of commuters was limited by

one glaring inconvenience: the railroad did not actually run all the

way to Manhattan. The islands of Manhattan and Long Island were

separated by the East River, and until 1899, no tracks ran across the

East River. Prior to 1899, all passengers heading to New York City

had to take the LIRR to a terminal at Long Island City. From there,

they would board ferries that would carry them across the East River

to terminals at 34th Street, East 7th Street, and James Slip (the

intersection of Front Street and South Street). According to railroad

historian Ron Ziel, the railroad maintained a large fleet of ferries,

tugboats, and steamboats to transport passengers and

freight across the river. For passengers, the transfer at Long Island

City was time consuming and unpleasant. Furthermore, all

passengers heading to New York City had to disembark and board

ferries at a single terminal. The result was a serious bottleneck,

which delayed passengers waiting to board ferries.27

The establishment of the first all rail route to Manhattan in 1899

did little to improve matters. The El Connection, as it was called,

was flawed in several respects. First, it only served a limited

number of customers: the entrance to the El structure was at Flatbush

Avenue in Brooklyn, and thus not conveniently accessible to most LIRR

trains. Consequently, the majority of Manhattan-bound passengers

continued to traverse the East River by ferry and the El Connection

did not significantly ameliorate the bottleneck that occurred each

day at the Long Island City ferry terminal. Second, the El Connection

had a bottleneck problem of its own at the Sands Street station. In

addition to the growing number of Long Island commuters, many

Brooklyn residents began riding these trains across the river to work

each day, causing further overcrowding and delays.28

The third major flaw with the El Connection was that it involved

a large number of transfers. Transfers inevitably take time

and inconvenience passengers. Passengers rode select LIRR trains into

the El structure entrance near the Flatbush Avenue terminal. The

original train continued along the El structure until Myrtle Avenue.

There passengers had to disembark and board a second train. This

second train took them to Sands Street in Brooklyn, at which point

they had to board a third train. The third train was operated by the

New York and Brooklyn Bridge Railroad, which would take them over the

Brooklyn Bridge and into Manhattan. For these reasons, the first

all-rail route from Long Island to Manhattan did not relieve the

inconveniences associated with commutation via the LIRR.29

The system of transport to

Manhattan, be it by ferry or the El Connection, was clearly

inadequate. Austin Corbin foresaw this problem before his death in

1896 and offered several proposals for improvement, including a

Corbin Bridge across the East River from the LIRR’s Long Island

City terminal. In 1895, he even went so far as to promise that “the Long

Island Railroad with its bridge over the East River will be at

the service of any steamship company which wishes to save time.”

The Corbin Bridge was never built, but William Baldwin, Corbin’s

successor, took it upon himself to remedy the problems associated

with the LIRR’s passenger service to Manhattan. When Baldwin’s

experiment with the El Connection proved insufficient, he resolved to

construct a direct rail route to Manhattan. Although Corbin had

obtained the necessary government permits, the project could not

proceed without massive capital.30

While the LIRR ferried passengers across the East River to Manhattan,

the Pennsylvania Railroad ferried passengers from the West across the

Hudson River to Manhattan. For reasons analogous to those recognized

by Baldwin, the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) was making plans to build

an all rail route to reach Manhattan from the West. Unlike the LIRR,

the PRR was one of the nation’s largest railroad syndicates

and consequently had the financial resources to launch such a

large undertaking. However, permission to build rail lines and a

terminal in the borough of Manhattan had been granted to the LIRR,

not the PRR. In 1900, Baldwin and the PRR finalized an agreement by

which the Pennsylvania Railroad would purchase the LIRR for $6

million provided that it would build a terminal in Manhattan and

ralroad tunnels under the East River. Under this arrangement, both

railroads (which remained operationally distinct until 1928) would be

able to operate direct rail service to Manhattan.

Pennsylvania Station and the East River tunnel project would take ten

years to complete at a cost of $125 million. Although

some individuals and op-ed writers lamented that “the Long Island

Railroad has been unique in that it has been exclusively a local road

. . . now all this is to be changed,” their lament did not override

the need for adequate service to Manhattan. LIRR service was vastly

improved; the number of commuters soared after the station and

tunnels opened in September

1910.31

Population, Commutation, and the Sunrise

Homeland

The construction of Pennsylvania Station and the East River

tunnels eliminated the major inconveniences that had plagued the LIRR’s

service to Manhattan and made commutation possible on a wide scale.

Prior to the completion of the tunnels, the number of people willing

to undertake the daily journey to Manhattan was limited by both the

railroad’s capacity and passenger inconvenience. The new

infrastructure gave the LIRR the capacity to transport hundreds of

thousands of people to and from New York City each day. With an

efficient direct line to Pennsylvania Station, the LIRR delivered

thousands of passengers per hour into the very heart of New York

City. The ambitious new LIRR president, Ralph Peters, proposed plans

for enlarging the capacity of the stretch of tracking that led into

the tunnels. He and the other railroad officers anticipated a “monumental

exodus from the city,” resulting in a massive rise in passengers

and passenger revenue. They estimated that both would increase as

much as 200 percent in the years following the project’s completion.32

The expectations of Pennsylvania Station’s planners were met

and exceeded in the two decades after its opening in 1910. Nassau

County’s population was 83,930 in 1910, 116,825 in 1915, 126,120 in

1920, 207,640 in 1925, and 303,053 in 1930. Its population increased

more than twofold between 1920 and 1930, making it the fastest

growing county in the United States. Suffolk County’s population

was 96,138 in 1910, 104,342 in 1915, 110,246 in 1920, 143,208 in

1925, and 161,055 in 1930. Though less spectacular than the growth of

Nassau County, this still represents a significant population

increase of 67.5 percent over twenty years. In 1927, the Chairman of

the Suburban Transit Engineering Board (a subsidiary of the Port of

New York Authority) announced that, since 1900, Long Island had grown

more rapidly than any other area in the New York metropolitan

region.33

The new residents were commuters. In nearly every Long

Island community the number of commuters increased markedly. Great

Neck, for example, was home to 132 commuters in 1911. By 1923, that

number had risen to 626. Over the same period, the number of

commuters in Freeport increased from 475 to 2,211 and the number in

Rockville Centre increased form 589 to 1,751. In 1911, the first full

year that the East River tunnels were in operation, 30 percent of all

LIRR passengers were commuters. By 1928, 61.7 percent of all LIRR

riders were commuters. During that time span, ridership had risen

from 33,000,000 passengers per year to over 118,000,000 passengers

per year. In 1928, no other similarly sized area in the world was

serviced by as many daily trains as Long Island. The new commuters

were generally not long timeLong Islanders who were now taking jobs

in New York City. They were salaried white-collar city men “whose

dream,” according to one observer in 1914, “is to own a home in a

healthy neighborhood.”34

To accommodate the rapidly rising population of new

commuters, construction companies built homes at an unprecedented

pace. Home construction reached a fever pitch as contractors rushed

to build “suburban homes for all business men who wish them.” In

Malverne for example, the Amsterdam Development and Sales Company

began constructing homes in 1912. By 1920, over 100 homes had been

built on land that had been used for agriculture just ten years

earlier. Elsewhere on Long Island, real estate companies such as the

Hewlett Land Improvement Company, the Freeport Land Company, Garden

City Development Company, and the Bellmore Land Improvement

Company developed residential communities aimed at the average middle

-class family. In yet another illustration of the railroad’s

importance to the suburbanization of Long Island, these companies

chartered trains to transport potential buyers to home sites under

construction. As Edward Smits, author of Nassau, Suburbia, U.S.A.,

writes: A definite change in Nassau’s population was

evident. Stimulated by railroad promotion of the area as both a

resort and a year-round home, its growth was increasingly

steady. Along both shores attractive communities were

developing for middle-class businessmen from the city, where

their families could live in a healthy semi -rural environment.

At its height in the 1920s, the demand for new housing employed

over 200 companies and 16,000 construction workers. What had once

been rural country was physically transformed as “vacant land

disappeared until the only distinction between community boundaries

became a street, a stream, or a lake.”35

The new residents had come in search

of the “Sunrise Homeland,” the catch phrase used most frequently

to conjure up the hybrid image of recreation and permanent residence

promoted by the railroad. The first half of the phrase (Sunrise)

alluded to Long Island’s recreational capacities. The second part

of the phrase (homeland) clearly speaks to the residential aspect

that the railroad wished to promote. The word “Sunrise” was

borrowed from the Sunrise Trail, an already popular phrase

used to describe the journey to Long Island’s vacation spots. As

Paula Brown wrote in the railroad’s 1923 pamphlet What Poets Say

About Long Island, The Land of the Sunrise Trails, “For balmy air,

sports/ And beautiful homes/ Take the Sunrise Trail.”36

Theodore Roosevelt, Long Island’s most celebrated citizen

during this era, embodied the “Sunrise Homeland” lifestyle. At

his Oyster Bay home, Sagamore Hill, Roosevelt and his family spent a

great deal of time engaged in their popularized “strenuous life”

of outdoor pursuits including swimming, tennis, and boating. They

provided a vivid advertisement of Long Island’s recreational

opportunities. Roosevelt was a close friend of Special Agent

Fullerton and was consequently willing to

cooperate with railroad management in whatever means they

thought beneficial. It is, unsurprisingly, from Teddy Roosevelt that

we find the most explicit endorsement for Long Island as the “Sunrise

Homeland.” He described the character of his home on Long Island as

“a great many things – birds and trees and books, and all things

beautiful, and horses and rifles and children and hard work and the joy of

life.” This same sentiment was summarized by the railroad’s

promotional material, which proclaimed, “Long Island is the ideal

– yes, that is the word – home-ground and playground.” The notion of

the Sunrise Homeland as a place where one’s family could live in a

recreational wonderland combined the railroad’s most potent

promotional concepts into a single ideal.37

It would be easy to characterize the LIRR’s promotional efforts as

a progression from resort promotion to residential promotion.

However, a linear construction of the LIRR’s promotional themes from

1880 to 1930 would be inaccurate. The LIRR continued to promote the

area’s merits as a vacation site well into the 1930s. More

precisely, the promotional

materials of this period reveal a struggling railroad seeking to

entice people to come to Long Island in any way possible. The

railroad’s promotional team, led by Special Agent Fullerton,

launched several different visions of Long Island that it hoped would

appeal to middle and upper-class New Yorkers. From 1900-1930, Long

Island was simultaneously promoted as an ideal vacation destination,

a recreational paradise, an ideal home for commuters, and a fertile

land for agricultural pursuits. The Passenger Department saw these

vastly different images as not only compatible but mutually

reinforcing.

With its vast publication efforts, the LIRR had been the

central author of a new vision of Long Island – a winning

combination of the recreational and the residential – the Sunrise

Homeland. It would undoubtedly be influenced and modified later on,

but the basic structure had been laid out. The Sunrise Homeland

signified a home of leisure that was solid, close to New York City,

conducive to family life, and fun. Long Island in 1930 was already a

well-known suburb of a great metropolis. Later waves of migration

eastward would merely confirm that identity.

NOTES:

1 Geoffrey L. Rossano, “Broader Networks of Modernization,”

in Between Ocean and Empire: An Illustrated History of Long Island,

ed. Robert B. Mackay, Geoffrey L. Rossano, and Carol A. Traynor, (Northridge,

CA: Windsor Publications, 1985), 160; Natalie A. Naylor, “Population

Statistics” in The Roots and Heritage of Hempstead Town, ed.

Natalie Naylor, (Interlaken, NY: Heart of the Lakes

Publishing, 1994), 226.

2 Ralph Henry Gabriel, The Evolution of Long Island: A Story of

Land and Sea (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1921), 132; E.B.

Hinsdale, History of the Long Island Railroad Company, 1834-1898 (New

York: The Evening Post Job Printing House, 1898), 4; The official

name of the railroad is the Long Island Rail Road. However, when

referred to as a corporate entity, it is the Long Island Railroad

Company; Jacqueline Overton, Long Island’s Story (Garden City, NY:

Doubleday Doran & Company, 1929), 230; Gabriel, 133; Hinsdale, 5.

See also Mildred H. Smith, Early History of the Long Island Railroad,

1834-1900 (Uniondale: Salisbury Printers, 1958).

3 Ron Ziel and George H. Foster, Steel Rails to the Sunrise (New

York: Hawthorn Books, 1965), 11; Hinsdale, 5.

4 For more on Poppenhusen see James E. Haas, “Conrad Poppenhusen:

A Biographical Sketch of the `Benefactor of College Point’

Emphasizing the Civil War Years,” Long Island Historical Journal 16

(Fall 2003/Spring 2004): 135-144.

5 Ziel and Foster, 13; Gabriel, 142.

6 Edward J. Smits, Nassau Suburbia, U.S.A.: 1899 to 1974 (Garden

City, NY: Doubleday & Company Inc., 1974), 118.

7 Robert B. MacKay, “Of Grand Hotels, Great Estates, Polo, and Princes” in

Between Ocean and Empire, 112-131, 112; Ziel and Foster, 38-39.

The Manhattan Beach Hotel and the Oriental Hotel were in

Coney Island. The Argyle Hotel was in Babylon. The second edition of

the book in which Robert MacKay’s article appeared was entitled:

Long Island: An Illustrated History, ed. Robert B. MacKay and Richard

F. Welch (Sun Valley, CA: American Historical Press, 2000).

8 MacKay, 114; Howard M. Smith, Long Island Illustrated (New

York: The Long Island Rail Road Company, 1903), 5.

9 Smith, Long Island Illustrated, 106; MacKay 112.

10 Annual Report of the Long Island Rail Road Company for the

Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1895 (Long Island City, NY: Long Island

Railroad Company, 1895), 18; (This pamphlet and many of the other

sources cited in this article can be found in the Nassau County

Museum Collection of the Long Island Studies Institute, Hofstra

University); Vincent F. Seyfried, The Long Island Rail Road: A

Comprehensive History: The Age of Expansion 3 (Garden City, NY:

self-published, 1961-1984), 159; MacKay, 114.

11 Smits, 4; A Campaign of Education and Good Will Conducted by

the Long Island Railroad During 1927-1928 (Long Island City, NY:

Harry

R. Gelwicks Co. Inc, 1928), 1. 12 Smith, Long Island Illustrated, 5;

Suburban Long Island, “The Sunrise Homeland” (New York: Long

Island Railroad Company and the Long Island Real Estate Board, 1921),

cover page.

13 Natalie A. Naylor, Professor Emeritus of History, Hofstra

University, interview by author, March 26, 2004, Hempstead, NY.

10,000 copies of Cyclists’ Paradise were printed for its first

issue in 1897 and it went through two additional issues. In addition,

The Agronomist had 16,000 subscribers.

14 Charles L. Sachs, The Blessed Isle: Hal B. Fullerton and His Image

of Long Island 1897-1927 (Interlaken, NY: Heart of the Lakes

Publishing, 1991), 36.

15 Smits, 161; Campaign of Education, 4; Long Island, America’s

Sunrise Land (New York: Long Island Railroad Company, 1926), cover

page; Campaign of Education, 4; Long Island, America’s Sunrise Land

(New York: Long Island Ra ilroad, 1930), 7.

16 Sachs, 24, 29, 32 and 36; Gabriel, 181; Gabriel, 181.

17 Sachs, 37 and 38.

18 Smits, 12; Eugene L. Armbruster, Long Island, Its Early Days

and Development (New York: The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 1914),

43; MacKay, 119, 127; Ketcham, 36.

19 Long Island Illustrated, (New York: Long Island Railroad

Company, 1900), 7. This pamphlet from 1900 will be cited as Long

Island Illustrated while Howard Smith’s 1903 pamphlet of the same

title will continue to be cited as Smith, Long Island Illustrated,

followed by the appropriate page number; Kenneth T. Jackson,

Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (New

York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 98; MacKay, 121.

20 Long Island Illustrated, 6; Long Island, America’s Sunris e

Land (1930), 15; MacKay, 119; Forest Hills hosted the U.S. Men’s Championship,

later known as the U.S. Open, from 1923-1978. It hosted the U.S.

Women’s Championship from 1935-1978.

21 MacKay, 119; Long Island, America’s Sunrise Land (1930),

15; MacKay, 120, 121.

22 Smith, Long Island Illustrated, 7; “Development of LI,” South

Side Messenger, February 23, 1911; Edith Loring Fullerton, The Lure

of the Land, A Call to Long Island: The Story of the Work of the Long

Island Railroad Company at Experimental Station Number One (New

York: The Long Island Railroad Company, 1906), 8.

23 MacKay, 119; Smits, 12.

24 Smits, 143.

25 Ketcham, 36;Sachs, 35; Long Island Illustrated, 5.

26 Long Island Illustrated, 4; Smits, 4.

27 “LIRR Celebrates 150 Years of Service to Long Island,” Along

the Tracks, 9 (New York: Long Island Rail Road, 1984); Ron Ziel,

LIRR historian and co-author of Steel Rails to the Sunrise, interview

by author, December 4, 2003, Southampton, NY.

28 “El” is short for elevated, because the tracks were raised above

street level.

29 Ziel and Foster, 41.

30 Austin Corbin, Quick Transit Between New York and London

(New York: self-published, 1895), 31.

31 A Brief History of the Long Island Rail Road, 69; Ziel and Foster,

75, 184; “Long Island Rail Road’s Checkered Career,” Brooklyn

Daily Eagle , June 8, 1901.

32 Correspondence Between the President and General Manager of

the Long Island Rail Road and the Board of Estimate and Apportionment

of the City of New York in Relation to Grade Crossing Matters

and Improvements in Queens Borough (New York: The Long Island

Railroad Company, n.d.), 17; Ziel and Foster, 190.

33 Naylor, 226; Henry J. Lee, ed, The Long Island Almanac and

Year Book 1930: A Book of Information Respecting Nassau and

Suffolk Counties (New York City: Eagle Library Publications, 1930),

241; Jackson, 176; Rossano, 178; Lee, Almanac and Year Book 1930,

241; Long Island Regional Planning Board, Historical Population of

Long Island Communities 1790-1980: Decennial Census Data

(Hauppauge, NY: Long Island Regional Planning Board, 1982), 16;

Daniel L. Turner, Suburban Transit Relief for the Long Island Sector

of the Metropolitan

District: An Address Delivered at the Second Annual Meeting,

Long Island Chamber of Commerce (New York: Long Island Chamber

of Commerce, 1928), 3.

34 Smits, 155-156; Ziel and Foster, 121; A Campaign of Education

and Good Will Conducted by the Long Island Railroad During

1927-1928

(Long Island City, NY: Harry R. Gelwicks Co. Inc., 1928), 1;

Statistical Railroad Summary, 1923-1929 (New York: Committee on

Public Relations of the Eastern Railroads, 1929); Sachs, 66;

Armbruster, 43. There were not many motor vehicles on Long Island

prior to World War I. In 1915, there were only 8,766 automobiles in

Nassau County for a population of 116,825 – hardly a common

possession. During the 1920s, car ownership became fairly common

among Long Island families.

35 “Development of LI,” South Side Messenger, February 24, 1911; Rossano,

176; “LIRR Celebrates 150 Years of Service to Long Island,” 13.

36 The phrase may have also been an allusion to the all night parties of

the Jay Gatsby-type millionaires who made their homes on Long

Island; What Poets Say About Long Island, The Land of the Sunrise

Trails (New York: The Long Island Railroad Company, 1923), 18.

37 Ziel and Foster, 49; Smits, 10; Long Island and Real Life (New

York: The Long Island Railroad Company, 1916), 7.