The Long Island Rail Road: A Comprehensive History, Part One: South Side R.R. of L.I.

by Vincent F. Seyfried 1961

Foreword

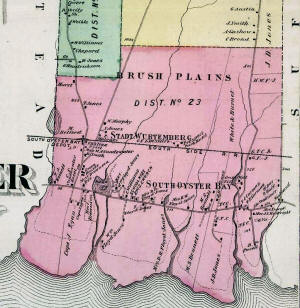

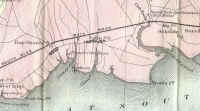

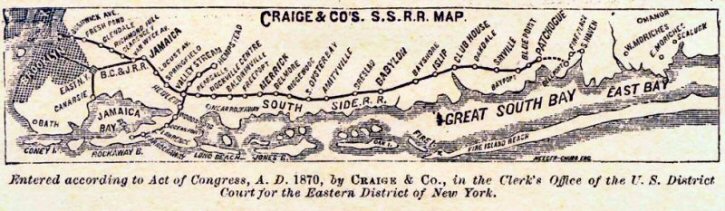

South Side Rail Road 1870 map Archive: Art

Huneke

Although the Long Island Rail Road traces its history back to1836 and is the third oldest line in the country, only two previous accounts of it have appeared: Elizur Hinsdale's brief history published in 1898, and Felix Reifschneider's longer and much fuller work published in 1922. In the forty years that have passed no comprehensive, intensively researched work has appeared.

The present volume seeks to present the full story of one of the Long Island Rail Road's first competitors: the South Side Railroad of Long Island, which operated the present Montauk Division as an independent railroad from 1867 to 1876.

After the lapse of almost a hundred years very few original sources have survived; only a single printed prospectus for a bond issue remains from South Side days. It has been necessary, therefore, to rely heavily on the contemporary newspapers for a day-to-day account of the road. Every surviving newspaper that published in any locality served by the South Side R.R. has been systematically searched for material. These include: THE PICKET, (Rockville Centre), 1865-1870; SOUTH SIDE SIGNAL, (Babylon), 1869-1880; FLUSHING DAILY TIMES, 1875-1880; BROOKLYN DAILY TIMES, 1863-1880; NEWTOWN REGISTER, 1873-1880; LONG ISLAND FARMER, (Jamaica), 1863-1871; LONG ISLAND DEMOCRAT, (Jamaica) 1863-1883. The valuable files of the PATCHOGUE ADVANCE and the SOUTH SIDE OBSERVER (Rockville Centre) for the 1870's are unfortunately lost.

A considerable body of new information on the railroad is brought forward here, much of it not known before. Even with this new accession of information, the reader may sometimes feel that a certain area of the road's history remains obscure; this may well be true, but, barring the improbable appearance of important new sources, we must be grateful that even this much has survived the destructive effects of fire, negligence and the many changes of administration.

It is hoped that this volume will be the first of several successive histories covering the full Long Island Rail Road and its predecessors; a second book on the Flushing, North Shore & Central Railroad is now in preparation. My thanks are due to Mr. William Rugen, who has furnished all the illustrations, and to Mr. Felix Reifschneider, who has read the manuscript, made many valuable suggestions, and arranged for the publication of the work.

CHAPTER I: The South Side RR Becomes a Reality

When the LIRR was first built and opened through to Greenport in 1844, its projectors thought of it as a direct route through to Boston, and somewhat a means of opening up to colonization the endless pine barrens through the center of the island. Historically, however, the oldest settlements on L.I. have been on the western end and all along the south shore. The original line of the LIRR, therefore, once it left Jamaica, passed through an uninhabited wilderness and served none of the old established and populous villages strung out along the south shore. Persons wishing to reach Brooklyn and Manhattan by rail had to make their way along the primitive roads inland to one of the lonely LIRR stations in the center of the island, and as this traffic grew, various stage coach routes sprang up to meet the increasing demand for public transportation. Several lines like the Deer Park-Babylon stage and the Hempstead-Freeport stage ran on regular schedules and carried many passengers.

In the 1850's transportation on the south side was further improved when the Plank Road companies took over the old wagon tracks and converted them into planked toll roads. The Merrick & Jamaica Plank Rd. Co. improved the Merrick Road between Jamaica and Merrick, while the South Oyster Bay Tpk. Co. improved the road from Hempstead to Merrick and on to Babylon (the present Babylon Turnpike and the Merrick Road). By 1860 there was a regular stage coach line between Amityville and Fulton Ferry which made two round trips a week, each round trip occupying three days, the middle day being allowed to rest the horses and to let the passengers transact their business. The stage was drawn by three horses and a relay was kept at Hempstead. It carried the mails for all the villages and the freights.

As the country entered the Civil War era, it became apparent that the stage coach could no longer meet the needs of the growing island. In 1860, therefore, a group of Long Island and Manhattan capitalists resolved to build a railroad from the East River to Patchogue all along the south shore of the island. The directors and president of the LIRR had been approached on several occasions to build such a road, or at least extend branches to the big villages, but they had always refused. It became clear that if a south side road was to be built at all, it would have to be built by independent capital.

Charles Fox of Baldwin was the leading spirit behind the organization of the new road. A wealthy man owning much real estate in Manhattan, a senior partner in the big clothing house of F. B. Baldwin and an alderman in New York, Fox induced a group of other wealthy men to invest in the new project. The Civil War forced the scheme into abeyance until 1865 because of the instability of the money market and the impossibility of obtaining iron. With the coming of peace in the spring of 1865, Fox and his men plunged energetically into the organization and building of their South Side Railroad of L.I. By summer the stocks and bonds of the new road had been printed and were placed on the market. As fast as the securities were sold, the road was to be built and it was hoped that ground would be broken in October.

In the fine Fall weather of 1865 the directors of the road personally visited all the men of means of their acquaintance along the south side towns. Next to Charles Fox, one of the road's most vigorous supporters was Willett Charlick, brother of Oliver Charlick, president of the Long Island R.R., and the deadliest enemy of the whole South Side RR scheme. Willett Charlick lived in Freeport and canvassed that area along with director Samuel DeMott; James Tuttle covered the Rockville Centre area and Martin Willets did the same for Babylon.

Stock and bond sales were slow in coming in. Some persons insisted the road would not pay, while others doubted that it would be built at all. It was hoped to raise by public subscription $250,000 in all. As the year 1865 drew to a close, all but about $40,000 had been paid in.

In January 1866 the road was formally incorporated and it was planned to begin construction as soon as the frost was out of the ground. Naturally enough, Charles Fox was elected president of the new organization; the treasurer was William J. Rushmore, president of the Atlantic National Bank in Brooklyn and a resident of Hempstead, and Alexander McCue, Corporation Counsel of Brooklyn, became treasurer. The vice-president was A. J. Bergen, member of the Assembly for Suffolk.

In March 1866 Oliver Charlick's friend, the "Long Island Star" ridiculed the new road because the articles of association and the maps had not yet been filed, but work went on just the same. Sales of stock continued encouraging and best' of all, many landholders were donating the right of way.

In April 1866 the road was advertised for contract. Sealed proposals were receivable at the company's office at 68 Wall St., New York, for grading, bridging, masonry, furnishing and laying of ties and rails for 34 miles of line from Jamaica to Islip. Plans and specifications were available as of May 1. Samuel McElroy was named Chief Engineer. Bids were to be closed on May 12.

The successful bidders were Shanahan, Meyers & Co. and the contract set April 1, 1867 as the completion date. The contractors started work on May 22 and immediately subcontracted the road into six sections, as follows:

- Jamaica to Springfield, 4 miles

- Springfield to Rockville Centre, 5½ miles

- Rockville Centre to Freeport, 4 miles

- Freeport to Hicksville Rd., Massapequa, 6 miles

- Massapequa to Islip, 15 miles

- Springfield to Rockville Centre, 5½ miles

Vandewater Smith, himself a director of the road and a contractor, was to furnish a third of the ties; Willett Charlick furnished a second third, and Martin Willets of Islip the remainder. Ties had to be 8 feet long, 4½ to 5 inches thick, and 6 inches wide dressed; any wood at all was acceptable. The railroad itself was to furnish the rolling stock.

On Monday, May 28, 1866 the dirt began to fly. A small work force began labor in Jamaica, while a second force was sent to work at Freeport and began grading westward.

In September 1866 at a meeting of the directors it was voted to extend the road from the present contracted terminus at Islip eleven miles eastward to Patchogue. This extension would not be laid, however, till 1867 or 1868; there was also talk of running a steamer from Patchogue to touch all the Great South Bay villages to the east.

During September 1866 additional gangs of workmen were set to work at the Hicksville Road (present Route 107) between the present stations of Seaford and Massapequa and work was pushed two miles to the east and west. Another gang was engaged near Amityville, grading through the swamp north of Ireland's Mill Pond (still existing) and a third graded through the swamp near Carman's Mill Pond (Massapequa Lake).

By the onset of winter weather in late November 1866, the grading of the road bed was largely finished between Jamaica and Islip. It was planned to lay ties and rails in the coming spring. The spectacle of actual physical work on the new railroad spurred the sale of the road's remaining securities, and in December Mr. Willett Charlick made the rounds of the bondholders for the first installment of 33 and 1/3%.

The enforced rest for the winter months was put to good use by the officials of the road in negotiating for a western outlet for the railroad. At first the directors approached the Brooklyn Central & Jamaica RR operating the line between Flatbush Avenue, Brooklyn, and Jamaica, but Oliver Charlick, the astute and Machiavellian president of the Long Island RR, managed to secure an indirect lease on the line for himself in November 1866, and so shut out the South Side R.R. from downtown Brooklyn. This left the road with the alternative of building its own line westward from Jamaica to a terminal in Long Island City or to Williamsburgh. After much deliberation it was decided to do both if possible. Overtures were made to the Brooklyn authorities to enter the Bushwick area via Metropolitan Ave., and to the New York & Flushing RR to lease that portion of their track along Newtown Creek between Maspeth and Long Island City. Since either terminus involved building at least as far west as Maspeth, another contract was let to grade a route through Richmond Hill, Glendale and Fresh Ponds, to be completed by July 1. Work began April 8, 1867. During May Messrs. Shanahan & Shields, the contractors, were busy grading between Maspeth and Glendale.

Meanwhile the more important task of working on the main line was resumed in April. Gangs of men with ties and rails were dispatched to South Jamaica and Springfield. Another gang began work on the eastern end of the road in May. In June enough rail had been laid at the Jamaica end to run an engine and work cars. Old Beaver Pond between Beaver Street and Liberty Avenue in Jamaica presented something of an obstacle to the railroad because of the swampy marshland on its edges; to overcome this the track was laid on driven piles, and the construction cars dumped load after load of dirt into the pond to make a sound roadbed and provide room for a station area and sidings. Orders were placed for three locomotives and the first passenger cars.

Over toward Newtown Creek in Maspeth work was also progressing. The railroad successfully negotiated the purchase of thirty-five acres of meadow land belonging to Calvary Cemetery between Jack's and Dutch Kills creeks with a valuable frontage along Newtown Creek on which to establish a freight and manure depot.

In Fresh Ponds the South Side laborers staged a local riot on pay day June 18, by getting drunk, shouting, insulting passers-by, and eventually forcing their way into houses where they belabored the owners and stole their valuables.

|

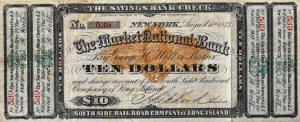

South Side

Railroad Stock Certificate Issued: 01/08/1867 Archive: John M. Szabol, Contribution: Art Huneke Collection |

During July 1867 the work of track laying progressed at the average rate of half a mile per day; track laying was going on simultaneously from Fresh Ponds to Jamaica and from Jamaica to about Valley Stream. Another track laying gang was moving west from Babylon. By the third week of August the rails reached Pearsall's (Lynbrook) and then a halt developed because of some difficulty between the officers of the road and Contractor Shanahan.

The work was further handicapped at this moment because of a severe injury to President Fox. He had attempted to board a Long Island train hurriedly at Mineola on the morning of August 5, 1867, moments before it had come to a final stop. In so doing, his foot slipped and he fell between the car and the station platform, the motion of the cars rolling him over and over in a space of seven or eight inches, causing severe internal injuries and breaking an arm. Doctors were summoned immediately who saved his life. A long period of recuperation became necessary and the active management of the road devolved upon one of the directors, Mr. A. J. Bergen of Islip.

During the first week of September the railhead reached Rockville Centre. The engine Charles Fox headed the construction work at this time and the south siders felt elated at the spectacle of this new iron horse puffing along, backing and returning; thirty to forty men were at work moving the railhead eastward.

By September 10 two engines were running construction trains, and two new passenger cars had been delivered at Hunter's Point; ten miles of track remained to be laid. At a meeting of the directors Mr. Ezra W. Conklin received the post of Chief Engineer replacing Samuel McElroy. On Monday September 23 the completed railhead reached the village of Freeport and the citizens went out of their way to welcome the construction train. All the residences were lighted up and a large number of people gathered at the railroad crossing at Main Street. Here sat the Charles Fox steaming away under an imposing arch bearing the inscription "Welcome to the Charles Fox," and on either side of the arch was suspended the Stars and Stripes. At the rear were the flat cars which served as platforms for the speakers and the brass band. Transparencies hung here and there adding a light and gay touch to the street. Decorations of evergreens and floral designs hung from poles all about and fireworks lit up the evening sky. Suitable short speeches were made and cheered to the echo, after which refreshments were served.

| SSRR South Oyster

Bay Depot map -1873

|

Five miles of rails remained to be laid. On October 11, 1867 the rails reached Babylon, and on the following day the Charles Fox with a passenger car attached containing the directors, passed over the road and were the recipients of numerous ovations at the different stations along the route. A brass band turned up at the Mineola Hotel where President Fox lay, recovering from his injuries, and serenaded him and he responded by inviting them all in for supper.

On Monday, October 28, 1867 the great day arrived, and trains began running regularly for the first time. The first trains enjoyed heavy patronage and met enthusiastic receptions all along the line. The very first schedule provided for two trains a day each way, one in the morning and one in the afternoon. The running time was one hour and fifteen minutes and the stations and fares were as follows:

| Jamaica to | ||||

| Springfield | 15¢ | Merrick | 45¢ | |

| Pearsall's | 25¢ | Ridgewood (Wantagh) | 55¢ | |

| Rockville Centre | 30¢ | South Oyster Bay (Massapequa) | 60¢ | |

| Baldwinsville | 35¢ | Amityville | 65¢ | |

| Freeport | 40¢ | Babylon | 85¢ |

The opening of the new road was acclaimed in all the Long Island newspapers and many persons turned out to see the new first-class locomotives and elegant passenger cars. A month before (September) the directors had succeeded in inducing Robert White, superintendent of the LIRR, to take over the same post on the South Side R.R. He was one of the most experienced railroad men available and brought to the road the energetic and competent management it needed.

On November 14, 1867 the South Side R.R. staged a formal grand opening of the completed road between Jamaica and Babylon. A five-car train was drawn up at the station and filled with the mayor, the whole Common Council, and prominent people of Brooklyn, plus the officers and directors of the South Side R.R. Other cars contained the prominent officials of Jamaica and Queens County, some Assemblymen from Albany and gentlemen of the press. The weather providentially turned out sunny and clear. After an hour's ride the train reached Babylon and the party was escorted to the American Hotel where "an elegant and sumptuous repast" was served. Speeches were made by the more prominent guests and the health of the absent President Fox was toasted. Later the guests sauntered about the streets of Babylon and then "took the cars" for Brooklyn.

Among the lyrical predictions of great things to come from the opening up of rich farmlands and thriving villages, many interesting facts emerged. The road cost $20,000 a mile including equipment; the company's capital was $1,250,000, of which $700,000 had already been expended. Popular enthusiasm along the line had resulted in the donation of several depot buildings. At Ridgewood (Wantagh) the depot had gone up by private subscription and the same thing was being done at Babylon. In addition much of the right of way had been donated outright by the farmers.

CHAPTER II: The South Side Rail Road Reaches the East River

While the company was completing its main line to Babylon, important events were happening on the west end of the line during the spring and summer of 1867. When the railhead approached the headwaters of Newtown Creek, it became necessary to make a decision: should the road seek its river-front terminal by going along the north bank of the creek into Long Island City, or should it follow the south bank into the Williamsburgh section of Brooklyn? Since the Long Island RR and the Flushing RR already had their termini in Long Island City, the company favored Brooklyn for its depot.

As early as the fall of 1866 long before the road turned a shovelful of earth, some of its promoters induced some of the prominent residents of Williamsburgh to support them in a petition addressed to the Common Council of Brooklyn to enter the city along the line of Metropolitan Avenue and North Third Street down to the ferry, and with a main depot at Union Avenue. The residents of the then very new village of Greenpoint signified that they were more than willing to let the railroad come through their area, should Brooklyn prove inhospitable.

Williamsburgh at the end of the Civil War had grown into a large city; between 1850 and 1855 it had been an independent city and had then merged into Brooklyn as the Eastern District. The Common Council was understandably hesitant about permitting a steam railroad to lay its tracks through a densely settled area where there was menace to life and limb. The Council wisely decided to open the question to public discussion and advertised public hearings in the press. The editors of the local papers seized upon the topic as one of paramount importance to the community, and threw open their columns to the widest public discussion.

Thanks to the long series of articles contributed by every shade of opinion, we can appreciate today the feelings pro and con about steam in the streets. In the Williamsburgh of the 1860's Bushwick Avenue, a north-south street, marked the limit of settlement. East of Bushwick Avenue stretched a very large area of swamp and meadowland forming the headwaters of Newtown Creek. No houses dotted this primeval greensward. Farmers pastured their cows in its fields and cut hay for winter fodder. Two roads only cut through the meadows: Maspeth Avenue and Metropolitan Avenue.

On the edge of the meadows and near the junction of the above avenues stood the old-time glue factory of Peter Cooper, one of the merchant princes of his day and the founder of Cooper Union. He owned nearly all the land in the area, while the Thursby family of ropewalk fame and the Kalbfleisch family (mayor of Brooklyn) owned the rest. The Coopers vigorously opposed the incursion of the South Side RR and led the opposition against the road. Cooper alleged that 100% of the people were opposed to the railroad and in rebuttal angry letters appeared in the Times attacking Cooper for self-interest and inaccuracy. The controversy raged unabated during May, June and July 1867 and finally came to a head in November and December.

Briefly, opponents of the South Side RR made these telling points against a line on Metropolitan Avenue to the ferry:

- Travelers from Long Island would simply pass through Williamsburgh and not spend any money in the District.

- The District contained twelve churches and three large public schools, the pupils of whom were threatened with maiming and death at the hands of the railroad.

- Steam cars would inevitably depress the value of building lots just coming onto the market.

- Steam would blight the residential area between the ferry and Bushwick Avenue, as had happened on Park Avenue and Eleventh Avenue in New York.

- The speed of steam cars will be greater than that of horse cars and so be a greater menace to pedestrians.

- A depot on the East River would crowd existing factories, and the trans-shipment of manure would make the area intolerable to residents.

- Metropolitan Avenue was narrow, twenty-four feet in some places and sixty feet at most anywhere, leaving no room for vehicular traffic.

-

Metropolitan Avenue varied widely in grade; a steep rise from the ferry to Bedford Avenue, a deep dip near Union Avenue, etc. The grade varied eight feet over all and because nineteen streets intersected it, cutting it down to a level for steam engines would be unthinkable.

Proponents of the South Side Rail Road urged these points in answer:

- Peter Cooper's opposition stems from his unwillingness to move his pestilential glue factory.

- A large produce market would be set up at the South Side terminus as an outlet for the Long Island farmers, providing fresh produce for all and employment for many.

- The railroad will not depress, but will rather increase the value of property along the street.

- Streets with railroads hum with life but wither away with the driving out of steam traffic; see what Atlantic Avenue was before 1861 and what it is now.

- Opposition to the South Side RR is being secretly abetted by President Oliver Charlick of the LIRR who fears competition, and the owners of the Long Island City ferries who fear loss of patronage.

- Quick, cheap transit to the suburbs is one of Brooklyn's crying needs.

- Access to Long Island summer resorts and beaches will be a boon to every Brooklyn family.

- Progress cannot be stopped by a Japanese policy of a closed door.

- The distance the railroad would go through crowded city streets is only a half mile to a Union Avenue depot or a mile to the ferry.

As the argument raged in the hearings and in the press, the local newspaper carne out strongly in favor of the South Side road. The Brooklyn Times and the Brooklyn Union championed the railroad, and the Eagle favored the idea. There were not wanting voices of compromise. Some suggested running the road to the Wallabout Basin (now the Navy Yard) along the lowlands marking the division between old Brooklyn and Williamsburgh, approximately along the line of Flushing Avenue, then sparsely settled. Another school of thinking viewed favorably a private right-of-way running midway between Maspeth and Metropolitan Avenues as far as Bushwick Avenue. Still others liked the idea of a line along Newtown Creek down to the East River by-passing Williamsburgh altogether.

In the first week of July 1867 the hot dispute came to a vote in the Common Council and the railroad was refused entry into Brooklyn along the line of Metropolitan Avenue with steam cars. In September the South Side RR again petitioned the Common Council to enter Brooklyn, this time along the line of Dickinson Avenue, then north up Vandervoort Avenue to Orient, and west along Orient Avenue to the jnuction of Metropolitan and Bushwick Avenues. This route was poor, involving two sharp turns, yet opposition again developed despite the absence of houses along the route.

As November 1867 wore on with no solution in sight, the Brooklyn Times editorially suggested that the South Side might achieve a river terminus cheaply and easily by going along the line of Bushwick Creek (North Thirteenth Street and through McCarren Park), the very route later to be chosen for the Manhattan Beach road, but intimated that the railroad should be satisfied with a depot on Bushwick Avenue.

The South Side RR made one last try before accepting the advice of the Times. On November 28, 1867 the road petitioned the Common Conucil to enter Brooklyn along the line of Montrose Avenue and to build a depot at Union Avenue. The advantages were that Montrose Avenue was eighty feet wide in Williamsburgh and that east of Bushwick Avenue, it existed only on paper, traversing a swamp and meadow with not a single house. From Bushwick to Union Avenue was densely populated, to be sure, but this stretch was only five blocks long.

No one at all objected to the meadowland route to the east, but for the five block stretch to Union Avenue there was strong opposition because of the dense population all about; all the old arguments against steam were trotted out and restated. Some one proposed a tunnel but the railroad engineers pointed out that the ground level was only seven to ten feet above high water and that the railroad was unable to expend the estimated cost of almost a million dollars.

As the year 1867 came to a close with the matter still deadlocked, the railroad accepted what had long been apparent: a terminus on the edge of the city (Bushwick Avenue) and the use of horses to pull the cars the rest of the distance to the ferry. As soon as the railroad made known its willingness to accept this compromise, the Common Council on December 16 gratefully ended the long dispute by granting a depot on Bushwick Avenue at Montrose Avenue and a single-track horse-operated road to the ferry at the foot of South Seventh Street.

When it became evident to the South Side RR that an outlet to the East River was certain, negotiations were begun to acquire a site on the waterfront for a depot. The company first negotiated for the Tuttle Coal Yard at Wythe and South Seventh but the price of $33,000 for 3 lots struck the directors as too high. The ferry stand at the foot of South Eighth Street, and a lot at South Eighth and Kent either cost too much or else provided insufficient space. After much searching about, the railroad finally managed to buy a plot of ground directly on the water between Broadway (old South Seventh Street) and South Eighth Street. The site had formerly been a coal yard and the railroad simply took over the existing office building as a freight depot. The property consisted of eight city lots, with a frontage on Kent Avenue of sixty-eight feet and a depth of 156 feet. Since the property directly adjoined the Broadway Ferry, it provided ideal accommodations for passengers.

With the depot problem solved at last, the South Side RR lost no time in building its track from Jamaica to the Broadway Ferry. As of December 1867 the track was completed from Jamaica to 118th Street., Richmond Hill, and the iron and ties were distributed along the line as far as Fresh Pond Road only three miles from the South Seventh Street ferry. The hard frosts and winter weather made track laying unsuitable, so the company used to good advantage the months of February and March in securing a route between Bushwick terminus and South Seventh Street ferry. On February 20, 1868 a petition was presented by the owners of property on Broadway to permit the railroad to run horse cars on Broadway. On March 2 the Common Council granted this request, giving the South Side a line along Montrose Avenue from Bushwick Avenue to Union Avenue, down Union Avenue a block to Broadway, and thence along Broadway to the ferry. The only conditions set were that the company should pave the rails with stone, operate only steam coaches, not park cars in the public street, and transport no manure.

While this arrangement seemed to please everybody at first sight, there was one hidden flaw. The Broadway R.R. Co., a street car company, was already operating a line of horse cars along Montrose Avenue to Bushwick Avenue. Rather than lay a second track beside that of the Broadway Company, or enter upon long and involved negotiations with them, President Fox of the South Side petitioned the Common Council to substitute Boerum Street instead, two blocks to the south. This time, miraculously, the permission was forthcoming immediately without long and dreary litigation.

With the entire route to Brooklyn cleared at last, the contractors building the road pushed their work. Just at this juncture, President Oliver Charlick of the LIRR shrewdly introduced another obstacle. As lessee of the Brooklyn Central & Jamaica RR since 1866, Charlick secured an injunction from the courts to prevent the South Side RR from crossing his road at Dunton west of Jamaica. It was but a delaying maneuver at best and within a month's time, the injunction was dissolved and construction continued onward.

By February 15, 1868 the gang had completed the track to Fresh Ponds and it was debated whether to open service immediately or wait to reach Brooklyn. On the nineteenth, as a party of workmen were excavating in a cut west of Fresh Pond Road, the bank suddenly caved in burying three men; thanks to prompt rescue work, all three were dug out uninjured. During April another gang was hard at work driving piles along the route through the meadows adjoining Newtown Creek. All during the fair spring weather the work was being pushed night and day and it was announced the road would enter Brooklyn by June 25. The heavy cutting involved in passing the ridge of hills near the Lutheran Cemetery proved the biggest obstacle.

On Saturday, July 18, 1868 the great day arrived after months of preparation; the first train passed over the South Side RR into Bushwick station, carrying 600 passengers. As yet there was no real depot. The railroad had taken over a farmhouse of Revolutionary vintage on the property, once the homestead of the Schenck family, and used it as a temporary waiting room and ticket office. The railroad had to rely on the Bushwick Avenue and Montrose Avenue horse cars to transport its passengers to the ferry, and there was lively competition for this privilege between the Brooklyn City and Broadway Railroads.

The opening of the South Side line to Brooklyn was welcomed as one of the greatest events in the history of Williamsburgh. The press saw it as a final rectification of the blunder of driving steam service from Atlantic Avenue seven years before. It was now possible to reach Jamaica in twenty minutes less time, and more important, brought the whole of the south side of Long Island into easy reach of Brooklyn. The new equipment and high standard of roadbed was favorably contrasted with the older Long Island RR, and looking far into the future, the press envisioned the many new villages and handsome residences that would grow up.

Even with the completion of the line into Bushwick, all did not run smoothly. In three days' time no less than four attempts were made to wreck the train by placing obstacles on the track; then on July 24 a torrential rain covered the track of the road with sand and water near Fresh Ponds and prevented service for half a day.

Laying of the rails into the ferry building was beset with difficulties. A sewer was being constructed along lower Broadway and the road was forced to wait till the work was done; in addition a horse car company operating on Union Avenue had been granted a terminus at South Eighth Street, and, as laid out, the railroad tracks and horse car rails would cross one another six times near Kent Avenue. To get out of this difficulty the South Side RR again appeared before the Common Council to exchange a portion of the two company's respective routes.

The permission to exchange track locations was easily forthcoming, but the Aldermen tacked on as a rider a prohibition against the use of T rail on Broadway, a right granted to the road in the earlier statute passed by the Council. Since part of the route was already laid with T rail, this eleventh-hour denial posed a new problem.

In the last days of September the tracks were laid through Boerum Street, and at the same time a large and commodious depot was going up at South Eighth Street. By the first week of November 1868, the work was almost completed; on November 4, Wednesday, the first train made the maiden trip through Brooklyn streets to the ferry terminus, eliminating at last the delay and inconvenience of changing cars at Bushwick. The South Side RR had at last reached the East River.

The South Side was not wholly satisfied with the new arrangement. Because the cars were drawn through Boerum Street and Broadway by horses, a train had to be broken up into individual cars, and a six-horse or eight-horse team attached to draw each coach to the ferry. In the railroad's view this process was cumbersome and increased the chances of accident. Using a steam dummy seemed the best solution.

Nothing quite like the old-fashioned steam dummy exists today; perhaps the closest modern analogy is the little diesel switcher popular in rail yards and freight terminals. In size the steam dummy resembled a small horse car of the period. It was very short with the conventional five or six windows and inside was a vertical steam boiler with a smokestack extending out through the roof. It had but four wheels driven directly by a piston and connecting rod from a small cylinder located near the front wheel. Because the engine ~was small and not very powerful, its smoke and cinder exhaust was small and hardly objectionable. Its chief advantage for the South Side RR was that it could haul a whole train of the frail wooden coaches of that period without the necessity of breaking up the train.

The use of steam through city streets necessitated another campaign of persuasion not only in the Brooklyn Common Council, but also in the State Legislature. Early in November 1868 the company applied to the Council for permission to experiment with a new dummy engine, to see whether the current models could draw cars on the grade along the eight blocks of South Eighth Street. The Brooklyn Times again took up the company's cause in its columns and urged the reasonableness of the idea.

A public hearing was called on December 3 and after much discussion, the use of a dummy was voted down. The chief objections were that steam engines were a threat to the safety of children, that they depreciated property, and created smoke. Most persons had no clear conception of the difference between a steam engine and a dummy, although company representatives stressed that the dummy's speed was only four to eight miles per hour and that seven to eight cars could be drawn at one time, and stopped within the dummy's own length.

When the Common Council met to consider the question, no remonstrance had been received from the property owners. The council members advised the road that if the company would substitute the groove rail for the present T rail, the matter might receive more favorable attention. Complaints had been received about wagons breaking axles. The railroad's representatives replied that an order had already been given to a Jersey factory for the grooved rails, but the order had not yet been filled. The Aldermen seemed dissatisfied at this and voted to leave the matter in abeyance till the rails were changed. On December 28 the matter was again brought up and permission at last given. The grant expressly stated that experimental trips only might be attempted on three days in January 1869, and as a further precaution, insisted that the engine be preceded by a horse with rider carrying a red flag; that bond against damages be executed, and that the T rail be eliminated at the earliest possible moment.

The South Side RR was not the first to try out steam dummies as a substitute for horse power. It had been tried intermittently on certain New York street car lines in 1864 (Second Avenue and Bleecker Street), in Philadelphia later, and in 1868 on Atlantic Avenue by the Atlantic Ave. RR Co. The New York & Hudson River RR was also using one on Eleventh Avenue in New York which the Brooklyn Aldermen themselves visited in January 1869. As a result of this visit the officials were very favorably impressed and renewed the South Side Rail Road's permission to test their engine in February, nothing having been done in January. In a burst of generosity they even withdrew the requirement to employ a horse and a red flag.

As soon as the permission was forthcoming, the South Side officials scouted around everywhere for a suitable dummy engine and found none for sale. As the weeks drifted by, it became necessary to place an order for an improved dummy with a firm in Jersey, and to petition the Common Council for an extension of time. With an eye to the future, the company also introduced a petition to the Assembly in Albany on March 11, praying for permission to use the dummy permanently in the streets of Brooklyn. On April 20 the bill was passed by the Assembly and referred to the Senate. Oliver Charlick of the Long Island~ RR and men of influence on the Long Island's Board of Directors were busy using every political connection they enjoyed to defeat the measure.

From a newspaper attack on the South Side RR in April led by a citizen of Williamsburgh, we learn that the company had failed to remove the T rail although it had promised to do so as soon as the frost was out of the ground. It was true that the new flat rails were stacked all along the curb in Boerum Street and Broadway, but no effort had been made to lay them. The writer bitterly denounced the double nuisance of T rail in the road and the obstruction to the sidewalk of the grooved rails; he pronounced the condition of lower Broadway so wretched between South Eighth and Boerum Streets that for eight or ten blocks the avenue was virtually closed to light carriages. The editor's comment did not disagree with these facts and expressed the hope that the South Side people would be stirred to action.

The letter must have been effective for during the first week of May the company removed a part of the T rails from Broadway and were installing the grooved rail to the pleasure and satisfaction of carriage drivers. The work proceeded at an irritatingly slow pace all during May and June and the discarded T rails lay in piles in the roadway, narrowing Broadway for wagon traffic.

Apparently the Senate Railroad Committee reported favorably on the dummy bill despite Charlick's machinations, for the company made ready all during June and July for the new dummy service. On Saturday July 31, 1869 a dummy made a trial trip at four P.M. along Boerum Street for the first time. It came down with four passenger cars and four freight cars. The trip took about ten minutes and closely observing the operation were President Fox and Superintendent White in one of the passenger cars. On Monday morning, August 2 the dummy began regular service hauling full trains back and forth. After a week of operation no accidents had occurred and no complaints lodged, moving the newspapers to comment on how groundless and old-maidish had been the fears of alarmists.

CHAPTER III: The Era of Expansion: Patchogue, Rockaway And Hunter's Point

With the all-important deep-water terminus in Brooklyn secured, the South Side RR next bent all its efforts to completing the east end of the line. Originally, the company had planned to build only as far as Islip, but it quickly became evident that the much larger village of Patchogue would make a better terminus. Long before the first train opened regular service to Babylon on October 28, 1867, the inhabitants of the south shore villages were actively discussing just how far eastward the railroad should be extended. While the directors of the road were perfectly receptive to the idea of building farther afield, Patchogue seemed an immediate and practical goal.

The contract for grading the roadbed east of Babylon seems to have been given out as early as January 1868. By the last week of March the engineers' surveys were completed, and grading was planned as soon as the ground thawed sufficiently. On April 2, 1868 track-laying between Babylon and Patchogue was commenced, and on April 30 was completed as far east as Islip. It was tentatively planned to open service to Islip on May 1; workmen meanwhile hastily pushed on toward Patchogue. By August the grading had been completed to Sayville and grading between here and Patchogue was begun. In the first week of September workmen began laying the rails eastward from Islip and on Saturday, September 5, trains were run into the village of Islip for the first time.

Grading meanwhile had been pushed to within a mile of Patchogue. By September 10 the grading gang had passed Sayville. As a temporary measure arrangements were made with the proprietor of the stagecoach running along the Montauk Highway to carry passengers from Patchogue to the end of track. On September 7, Labor Day, no less than eighty passengers were so conveyed, something of a record for so small a vehicle on one day and almost a century ago. By September 21 the grading had approached to within a mile and a half of Patchogue. As autumn passed on into late October, the railroad came close to Sayville and the grading work into Patchogue reached completion; Superintendent White announced to the newspapers that service would begin to Sayville "in a fortnight."

|

|

In the first week of December Jack Frost put an end to all grading operations for the winter, but on or about December 11 Superintendent White did inaugurate the service to Sayville station as planned. So pleased were the residents of the town at having the trains before winter closed in that on Sunday the thirteenth, a large group of townsmen joined fifty of the railroad's employees in erecting and completing an engine house all in one day. Work necessarily came to a halt during the coldest winter months, but in March the railroad resumed work on the road, and pushed it as fast as the ground would allow. Finally, on or about April 10, 1869 the line was completed to Patchogue. One would suppose that the completion of the main line would have occasioned some sort of celebration, but the event must have been a quiet and casual affair, for it passed unchronicled in any of the newspapers of the island.

The mere presence of the South Side RR was a stimulus to all the villages along the south shore from the very day that the road had been organized. In an age when railroad facilities were a prestige symbol for a town and meant the difference between isolation and partnership with progress, forward looking townsmen and merchants in every village took it upon themselves to initiate promotion campaigns and to offer tempting inducements to railroad boards of directors to extend to their locality.

As early as January 1867, long before the first tie had been laid, the citizens of Moriches held a meeting and voted to grant the right-of-way through their land to the company. Not to be outdone in generosity, the landowners near Sag Harbor offered the same inducement in March. To smooth the advance of the railroad legally, committees arranged for the presentation to the Legislature of bills authorizing extension of the road through the Towns of Brookhaven and Southampton, and offered to market railroad bonds to the amount of eight and ten thousand dollars per mile of road built.

During the winter months of 1867-8 rallies were held in the principal villages to whip up railroad enthusiasm and in April the three townships of Brookhaven, Southampton and Easthampton came through handsomely with generous offers of money and land. Brookhaven offered $68,000 and the right of way, Southampton $112,000 and the right of way, and Easthampton $25,000, a grand total of $205,000 toward the completion of about forty-five miles of road eastward from Patchogue to Sag Harbor. This generous offer was presented to the directors of the South Side RR at their meeting on April 6, 1868 and unanimously accepted.

With the coming of spring in 1869, it was reliably reported that the directors were about to build along the proffered right of way from Patchogue through Bellport, Brookhaven, and Moriches to Riverhead, the county seat. The inhabitants of Riverhead declared themselves ready to vote $25,000 or more to encourage the enterprise.

Whatever the reason, nothing so grandiose as a Riverhead extension took place over the summer, but in the fall of 1869 commissioners were appointed to appraise the damages to property for a four-mile extension from Patchogue to the neighboring village of Bellport, in the hope that construction could begin in the spring of 1870. The people of Moriches, at a public meeting, also took the occasion to appoint a committee to wait upon President Fox of the South Side RR to persuade him to build as far as Eastport, the easterly limit of the Town of Brookhaven. President Fox replied that the request would be favorably considered, provided the residents along the proposed extension would subscribe for $140,000 of the first mortgage bonds of the railroad. At a meeting of the directors on the twenty-second it was voted to make a survey of the road.

In January it was reported that the $140,000 of stock had all been taken by the residents of the various villages, and that the engineering survey was being pushed. Then, oddly enough, all talk of eastward extensions ceased, and we hear of no further attempts either on the part of the villages or the railroad to move eastward. It is difficult to see after the lapse of a century just why this was so. We can only surmise that the tempting offers of stock and land were not as readily forthcoming as the railroad was led to expect, or, more likely, that the Long Island Rail Road's hasty extension to Sag Harbor just a few months later on June 8, 1870 siphoned off what little traffic originated on the east end.

The directors of the South Side RR were too astute and forward looking however, to waste the season of 1869 in idleness. From the very earliest days of the incorporation of the road, they had cast an appraising eye on the traffic possibilities of the Rockaways, as yet untapped by the Long Island RR. Before the Civil War, surf bathing and beach visiting were virtually unknown; it is difficult to imagine in our day when sun bathing and swimming have become a national cult and part of the mores of American society, that great beaches like Coney Island and Rockaway, only a few miles from the metropolis, were deserted and barren sand dunes.

In 1816 the Pavilion, the first seaside resort hotel in Rockaway opened its doors. During the 1830's visiting the Pavilion became fashionable, but not for the bathing facilities available. Persons of wealth boarded at the shore, ate quantities of "Rockaways," the most esteemed clams of that day, and attended cotillions and concerts in the evening. Life had a leisurely and aristocratic flavor, and none but the wealthy could afford the long, costly trip to the beach.

When the Pavilion burned down in 1863, it marked the end of an era. Hitherto, to get to Far Rockaway, one took the train to Jamaica, and then hired a stage coach to traverse the swampy stretches of the Jamaica & Rockaway Turnpike Co. (Rockaway Boulevard) to the shore. In October 1865 this primitive mode of travel was rendered obsolete by the opening of the Brooklyn and Rockaway Beach RR from East New York due south to Canarsie, where the traveler boarded one of the railroad's launches to anyone of three landings, presently corresponding to Beach 111th Street, Beach 103rd Street and Beach 92nd Street.

The effect of the Canarsie route was to attract traffic to the present Hammel's, Seaside and Rockaway Beach and away from Far Rockaway. A further injury occurred in 1866 when the spring tides caused a long sand bar to form opposite the old Far Rockaway Beach about half a mile out in the water. The bar gradually grew and cut off the breakers, ruining surf bathing. In April 1870 the same spring tides in the course of one evening swept over the island and washed it away to the great joy of the inhabitants, who prayed for a return of the old days when Far Rockaway was known as one of the best surf bathing beaches in the country.

The vast increase in population in Brooklyn and Williamsburgh during the 1860'S because of the record immigration of Irish and Germans is another factor that must be considered in explaining the sudden popularity of the beaches in the late Sixties and early Seventies. These city dwellers lived closely together, raised large families, and worked six days a week; it was inevitable that cheap recreation would attract an overwhelming patronage.

With this potential bonanza in mind, the directors of the South Side RR resolved in 1868 to be the first to build a direct, overland route to the Rockaways. Because the charter of the South Side RR did not expressly permit the construction of a branch to the Rockaways, the directors had to incorporate a subsidiary called the "Far Rockaway Branch Rail Road Co. of Queens County." with Vandewater Smith, one of the directors, as its president.

On March 24, 1869 three hundred men were put to work at a point then known as Wood's Corner, near the Brush Farm, later Franklin Ave., Valley Stream. At almost the same time Electus B. Litchfield, the wealthy railroad magnate of Brooklyn and Babylon, purchased the whole J. N. Brush farm of eighty-five acres in all, for about $20,000 and laid out what became the village of Valley Stream. In the early days of April the work on the new branch accelerated; at the time 160 laborers had graded two miles of road, and on April 10 began laying the ties and rails. By the first of May the whole road had been graded.

Some of the right of way must have been secured by the issuance of lifetime passes to the property holders. We learn this indirectly from an amusing incident that occurred in the fall of this year 1869. An old man, a Mr. Norton, venerable with white hairs, took his seat in the coach with his aged wife. Something evidently excited the old man, for in an undertone he was laying down the law to his companion accompanied with violent gestures. When the conductor arrived, his excitement seemed to culminate. On inquiry it developed that for certain considerations President Vandewater Smith had bargained to allow Mr. Norton and his wife a free pass over the Rockaway and South Side Railroads during their natural lives. The trouble of the old man was that his pass was only dated for one year and had to be renewed each year, whereas he wished it to be perpetual without the burden of renewing it annually.

Just when the progress of the road was all that could be desired, a hitch developed in relation to some real estate. A Mr. William B. McManus who owned a farm located between Rockaway Turnpike and Washington Avenue, Lawrence, and which would be cut in two by the railroad right of way, refused to accept the railroad's valuation on his property, and successfully petitioned for an injunction on May 30, 1869.

This was a severe blow to the railroad's hopes for they were bending every effort to open the line in time for the summer patronage; in desperation they formulated an emergency plan to run trains as far as the McManus property, and convey passengers the rest of the way by stagecoach. By a legal quirk this proved unnecessary; McManus' injunction against the South Side RR expired at 11 A.M. on June 24, and before McManus had time to have it renewed, a force of about seventy men laid the ties and rails over the 7oo-foot distance within three hours and a construction train ran over it. The railroad hoped to surface up and level the track and roadbed over the weekend of June 26-27 and then begin service.

McManus had probably not realized that the railroad was capable of such sharp dealing, but neither did the railroad realize the sort of man they were dealing with. The following night McManus rounded up a group of fellow Irishmen and not only tore up the 700 feet of track, but did it so thoroughly that every rail was ruined in the process of removal.

The railroad was jolted by this unusual show of spirit and began proceedings to discover the culprits. The following weekend McManus was arrested on a complaint of Vandewater Smith, president of the Far Rockaway Branch RR, on charges of malicious and willful destruction. McManus was discharged on a legal objection that the complaint did not state facts sufficient to bring the defendant within the provisions of the statute. President Smith objected to dismissing the suit and a new hearing was scheduled.

Meanwhile McManus' counsel threatened that he would sell or otherwise dispose of the track and crossties if not removed from the premises, and this so alarmed the railroad that they secured an injunction from the Supreme Court forbidding any tampering with their property until final adjudication.

At the next court hearing three commissioners were appointed to assess the McManus property and to make an award. On July 23, 1869 the commissioners inspected the land and after conferring, confirmed an award of $425 to McManus. Predictably, that gentleman flew into a rage and planned to appeal from the decision. Meanwhile, the railroad relaid its ravaged roadbed on July 28.

On Thursday, July 29, 1869 the branch road to Far Rockaway was opened to the public. The importance of the new route could hardly be overestimated. For the first time Rockaway was brought into direct communication with Brooklyn, and it became possible for the average man to visit the beach for the day after traveling for only forty minutes. The total investment for the company came to about $75,000, but it was hoped that the returns would be many times that sum.

South Side Rail Road - Far Rockaway Archive: Art Huneke |

The South Side RR terminal depot and roundhouse in Far Rockaway occupied the present site of the Long Island RR's depot facing Mott Avenue. Because the South Side terminal was at the north end of the village of Far Rockaway, passengers still had the long distance of a mile to walk to the bathing beach and had to compete for space with the boarders of the many hotels in the village. West of the present Beach Twentieth Street there were no houses or hotels, and the beach and sand dunes stretched for miles; it occurred to the railroad directors that simply by constructing a sweeping curve along the north and west of the village, they could have a terminus right at the water's edge with a beach of their own.

With this object in mind the road initiated fresh construction in July 1869. By the end of August the required one mile of track was completed to the dune headlands between Edgemere and Wave Crest and terminating at a point which today is approximately Beach Thirtieth Street and the Boardwalk. On September 1 the new spur was completed and excursion tickets were put on sale for September 2, entitling the purchaser to a round trip ride, a free lunch and participation in a clambake, in honor of the inauguration of the new line.

On Thursday, September 2, 1869 the new road was opened as planned. President Charles Fox of the South Side RR and Vandewater Smith of the Far Rockaway Branch road, along with many directors and their families, came down to the beach and filled the large tents surrounding the clam pits. Lunch was served to about 200 guests of the railroad present and short speeches were made by the two presidents to mark the occasion, followed by an inspection of the neighborhood. During the following spring of the 1870 season the railroad erected a large restaurant or pavilion 125 x 200 feet on the beach facing the ocean for the convenience of its patrons. Connected with it was a kitchen and rooms for the keeper and his family. On timetables this structure was first referred to simply as "Beach," later "Beach House," and after 1872 as "South Side Pavilion."

By the summer of 1870 the South Side Pavilion was in full operation. There was a large "saloon" where individuals or parties could buy a substantial meal at popular prices, or if they preferred, could occupy guest tables at a rental of twenty-five cents. A string band was provided by the railroad every afternoon for persons wishing to dance. On the beach side there were bath houses, where the railroad rented out bathing suits and extended facilities for checking valuables. A plank walk led from the open depot tracks to the water's edge. So proud was the railroad of its Beach House that it ran another private Rockaway excursion for its board of directors on August 3, 1870.

In **1871 the railroad entrusted the management of the South Side Pavilion to professional operators, Messrs. Hicks & Dibble. On June 5 the place was officially opened for the season and the railroad again ran a private excursion consisting of three coaches and the locomotive "J. B. Johnston" for the benefit of railroad executives, politicians and guests, all of whom partook liberally of the clam roasts and clam chowders for which the house was noted, and later regaled themselves with the yachting and bluefishing facilities.

As the 1871 season wore on, the directors resolved on a new and still more impressive improvement; this was to extend the tracks westward from the South Side Pavilion all the way along the Rockaway peninsula as far as the limit of habitation.

One motive behind this extension was to capture all the Rockaway passenger traffic which up to then had been shared with the Brooklyn & Rockaway Beach RR Co., operating from East New York to Canarsie. While Far Rockaway was an old seaside resort of half a century's standing, the peninsula itself had been slowly developing and was in 1870 the exclusive preserve of four or five hotels. In 1856 James S. Remsen of Jamaica bought a considerable tract of land at Rockaway Beach for $500. In this primitive wilderness he built a little barroom and chowder house, which over the years gradually developed into the Seaside House.

At first the house catered only to fisherfolk and boat parties, but after the Brooklyn & Rockaway Beach RR opened in October 1865, a bay landing was constructed at Remsen Avenue (Beach 103rd Street) and the railroad's ferry boats disgorged Rockaway's first beach crowds visiting just for the day, and intent on swimming, picnicking and gargantuan clam and oyster-eating orgies. Remsen sold some of his land for enormous sums and rented out the rest, including the Seaside House, which, by 1869, was the largest establishment along the dunes. It was this seaside resort that exerted a magnetic appeal on the directors of the South Side RR, and it was towards this goal that fresh construction began in April and May 1872.

There was a second and more immediate motive for building the beach extension in 1872, the unpleasant fact that Oliver Charlick of the Long Island RR was building his own Rockaway Branch from Rockaway Junction (present Hillside station) southward to an undefined point. Unless the South Side RR built immediately westward from their pavilion, their rival Charlick would beat them to the punch. Work was rushed on the new line, which was laid along the highest point of the beach ridge, affording a fine view of the ocean.

On July 4, 1872 the new line opened through to the Seaside House (Beach 103rd Street, Seaside Station). There were two intermediate stations: Eldert's Grove (Beach Eighty-fourth Street, now Hammel's) and Holland's (Beach Ninety-second Street, now Holland Station). Both of these were resort hotels, the one run by Garry Eldert and the other by Michael Holland. Two years later in May 1875 the directors extended the branch one step further to the Neptune House (Beach 116th Street) which became the permanent terminus.

With the extension to the Rockaways an assured success that would grow with the years, the South Side RR resolved to go through with another project which had been under discussion for some time, namely, a branch to Hunter's Point. During the long negotiations with the City of Brooklyn during 1867 and 1868 for an outlet to the East River, the alternative of reaching the waterfront by a route along Newtown Creek to Hunter's Point had frequently come up, and had been used as a potent argument in case the city authorities should prove balky.

Even with the Brooklyn route secured, the railroad was not completely satisfied. The biggest handicap was the difficulty in shuttling freight cars back and forth from the ferry to Bushwick station along a single track through streets crowded with wagons and horse cars, and with the ever-present menace of children and venturesome boys. By building a branch along the north side of Newtown Creek, the road could obtain a deep water terminal without the handicaps of the Williamsburgh route, but such a road would be expensive because of the right-of-way through commercial properties, and because it would meet the certain opposition of the Long Island RR and its politically formidable president, Oliver Charlick.

Now it so happened that there was already such a railroad along the creek from Maspeth to Hunter's Point built by the New York & Flushing RR in 1854. If the South Side RR were to obtain control of this road and build a short connecting spur, a road of its own would be unnecessary. In May 1867 the newspapers reported that the South Side and Flushing railroads were negotiating an agreement by which the former was to use the latter's tracks from Blissville to Hunter's Point, where the South Side would use the Long Dock just south of the LIRR depot. A depot would be erected at Vernon Blvd. and Newtown Creek for the South Side trains.

No sooner did Oliver Charlick, president of the LIRR, get wind of this deal than he himself began making attractive offers to the New York & Flushing RR for their property. With his many political and business connections, plus his own and his railroad's considerable financial backing, Charlick was easily in a position to outbid the South Side people, and in July 1867, to no one's surprise, he obtained control of the road. With access to Hunter's Point effectively cut off, the South Side RR had to be content with a Brooklyn terminus. Oliver Charlick, meanwhile, had no personal interest in the New York & Flushing now that the South Side RR had given up hope of acquiring it, and within a year's time (August 1868) he sold it again to a group of Flushing business men.

This act proved to be one of Oliver Charlick's very few mistakes in judgment, for no sooner had the road been sold than the South Side again sought to exercise the option it claimed to have secured in May 1867, and reportedly began preparations to construct a connection. All sorts of legal difficulties created by the Long Island RR delayed matters, but in October 1869, it was reported that the South Side had completed the purchase of a portion of the New York & Flushing line. By the new agreement the South Side became undisputed owner of the old New York & Flushing right-of-way from Winfield Junction to the Hunter's Point dock at a reported price of $40,000 per mile. The New York & Flushing had, during this very month of October 1869, accommodatingly constructed a new route for itself into Long Island City and willingly disposed of the old route.

During November the surveying team of the South Side RR toured the right-of-way and reported that it would be necessary to build a spur of one and one-tenth miles from Fresh Ponds to Blissville to complete the connection between the two roads. The exact point of the connection was the present Forty-ninth Street and Fifty-sixth Road, immediately west of the present Haberman station. Again the South Side found it legally necessary to set up a subsidiary to build the spur and the "South Side Connection Railroad Co." was duly incorporated with one of the directors as president. On December 4, 1869 the contract to build the connection was formally awarded to Robert White, ex-superintendent of the road and now a director, and James Wright.

Work on the connection began on Tuesday morning, December 7. Because the old New York & Flushing rails were of very light iron, it was decided to rebuild the old roadbed to the same standards as the rest of the South Side, i.e. thorough ballasting and sixty-pound rails. New culverts and bridges were also to be constructed to withstand heavier loads. Despite the winter weather contractors pushed the construction of the connection energetically in December and January; early in February the road was reported as "about completed", and to open by May 1. During the first week of April the grading of the roadbed reached completion and the laying of the rails had begun.

Just as everything was going along smoothly, the South Side RR experienced a repetition of its Rockaway experience. Mr. William E. Furman, ex-sheriff and a member of one of the pioneer families of Queens, lived in a mansion on the north side of Maspeth Ave. at 57th St. South of the house on the now obliterated Shanty Creek Mr. Furman had constructed one of the show places of Long Island, a complete trout-breeding farm. Fresh water from springs passing west into Newtown Creek was diverted through a series of S-shaped sluices, bedded with gravel and sand for spawning. When the surveyors laid out the track through the Furman property, they located it within about five feet of Mr. Furman's house. He offered the railroad additional land and $2000 to change their route, but they reportedly refused, whereupon he procured an injunction. A week later on April 28 the injunction was lifted. It was then given out that the trouble was not one of route, as the sheriff had consented that the line be run within eighty feet of the house, but as to the amount of land damage, Mr. Furman asking $8000 and the commissioners awarding only $2250.

With peace restored the work of grading was continued and some of the track work done. As the railroad approached closer and closer to Hunter's Point, it decided to make renewed efforts to get possession of the Hunter's Point dock. It happened that the Long Island RR owned the approaches to the dock, and because President Charlick refused the right to cross his land, the property was nearly worthless. The South Side RR then successfully petitioned the Legislature to open a street across the Long Island RR property, whereupon Charlick countered by producing a lease on the old Long Dock property to himself, which he claimed to have executed in his own favor during his brief tenure as president of the New York & Flushing (1867-68).

The South Side, checkmated, decided that if this lease could be vacated, they would build a depot on the Long Dock property; if not, they would cross over the Long Island RR tracks and use the Flushing RR depot. In July or August the railroad filed an ejectment suit against the Long Island RR to gain possession.

Meanwhile on May 31, 1870 the physical connection between the two roads was completed, and a South Side engine and construction train steamed into Hunter's Point for the first time. The segment of the old Flushing railroad between Forty-ninth Street, Blissville and Winfield was of no immediate value to the railroad, and originated no traffic since it passed entirely through farmland. The South Side management, rather than tear up the track entirely, placed a dummy, acquired cheaply from the Atlantic Avenue RR, on the route on August 6, 1870. Twenty trips were made each way, commencing at 5:30 A.M. from Winfield, and the last car reaching Hunter's Point at 10:27 P.M. Three stops were made on the route: Calvary Cemetery (Greenpoint Ave., the old cemetery gate), Penny Bridge (Laurel Hill Blvd.), and Maspeth (Borden Ave.?) We hear nothing further of this service, nor is this stretch of track ever mentioned again. It is not hard to surmise that the lonesome route, which passed through no hamlets at all, originated almost no revenue traffic. The South Side RR undoubtedly retained the right of way and the track, for the road is again mentioned in December 1875, when there was some idea of reviving it as a freight line.

CHAPTER IV: Operations: 1867-1872

In the preceding pages we have detailed at some length the building of the main line of the South Side RR and the various branches constructed shortly after. Let us now pause to consider the physical plant of the constructed railroad insofar as that is possible after the lapse of ninety years.

| South Side Rail Road - 1870

Freight House, Bushwick Photo: 10/1984 Art Huneke |

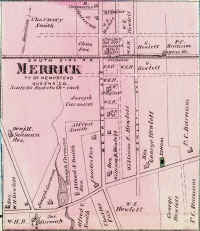

For the first three years (1867-1870) the entire South Side line was a single-track road with sidings, exactly like the Long Island RR and almost all the other roads of that day. There was yard trackage at South Eighth Street terminus and at Bushwick station, and additional turnouts were located at Hebbard's (Newtown Siding), now Fifty-second Street, Maspeth; Fresh Pond, a long siding between Van Wyck Avenue and Jamaica, Valley Stream, Merrick, Babylon (Carll Avenue to Deer Park Avenue) and Patchogue. In October 1869 another turnout was added at Rockville Centre and another at Baldwin; an engine house and turntable at Merrick was added in the fall of 1869. The Rockaway Branch appears to have remained single track throughout the life of the road. On this line there were but two turnouts, one between Valley Stream and Woodmere, and the other at Far Rockaway station.

The decision to double track most of the road (Valley Stream westward) was taken by the directors in the fall of 1870. Such a decision was a prestigious one, the import of which we can scarcely appreciate today. Only the big first class roads of that day could boast of any double-track sections, and the South Side RR was, after all, a newcomer with a background of only three years. It was an impressive testimony to the general prosperity of the road in the teeth of the older Long Island Railroad's opposition and a testimony to the directors' faith in the future.

As early as November 1870 gangs of men were put to work at a number of points along the road. Apparently the work was done in sections, for on November 29, 1870 the easternmost section was contracted out and on December 5 the westernmost end was let out to a Mr. Thompson. The oncoming of heavy winter weather in December put an end to the project, but the work was resumed in the spring of 1871. Early in April the track gang began at Valley Stream and by the end of the month had completed the work as far as Springfield.

| South Side Rail

Road - Springfield Station View SW Archive: Art Huneke Service

began: 10/28/1867. Depot built: Aug/Sept 1871 (4-year

gap??). Moved to Laurelton: 8/1876 Razed: 1906

Info: Dave Keller

Photo: c.1878 |

Grading over the whole route from Valley Stream to Bushwick had already been completed and the ties and iron distributed along the line. By May 8 the track gang reached Jamaica. Glendale was reached on June 6. In Jamaica the marshy border of Beaver Pond prevented the enlargement of the track facilities there, and the company adopted the expedient of buying an acre of land and taking all the sand and gravel on it for use as fill in grading across Beaver Pond. Some time during July the track layers reached Hebbard's at 52nd Street, Maspeth, the western limit planned for the double track. Because of the marshy nature of the ground around Newtown Creek and the great expense involved in spiling, about one mile of the road was allowed to remain as a single track stretch. Sometime in early October the second track was thrown open to traffic for its full length.

Not all of the road's original double tracking project was carried through to completion exactly as planned. One of the most difficult spots was Jamaica station, where the South Side depot was squeezed between the LIRR and Beaver Pond. In March of 1871 the company applied to the Jamaica Village trustees for permission to straighten their track, build a double track and erect depot buildings. This project involved changing the line of the rails somewhat and altering the grade. The trustees signified a willingness to have the road do this, provided the company would agree to a few conditions, such as stationing flagmen and laying new culverts. President Fox assured the trustees that he was willing to agree to the conditions, but for some reason refused to put the agreement in writing. The village trustees insisted and Fox, in a huff, attempted to go ahead with the alterations without consent. The trustees then secured an injunction. The railroad countered by refusing to stop three of its commuter trains at Jamaica and threatened to by-pass the village altogether after September 1.

The railroad was, of course, obligated to stop at Jamaica by the terms of its charter agreement with the Village of Jamaica at the time of its construction; there was also a mail contract with the Federal government and a legal obligation to its commuters. Nevertheless, its engineers were commissioned to plan a new route and in August 1871 came up with a surprising proposal.

If one glances at the right of way of the present Montauk division of the LIRR, it will be apparent that the road, after a comparatively long straight run through Glendale and Richmond Hill, bends sharply eastward at Morris Park to enter Jamaica, and then curves sharply south again east of the village toward Cedar Manor. The engineers pointed out that by constructing a connection from about Morris Park across to Cedar Manor, a straight line right-of-way would result, and the expense of spiling and filling at Beaver Pond could be saved. The right-of-way could be cheaply obtained and the new Jamaica depot would be outside the control of the trustees.

When the New York newspapers got wind of the dispute, they sent reporters who turned in inaccurate and distorted accounts of the squabbles and drummed up the whole affair into a "railroad war." President Fox, believing some of the copy he read, even sent two detectives to Jamaica who skulked about the village streets, furtively eyeing the citizens for signs of violence against company property. Late in August the entire squabble collapsed when President Fox signed the original terms proffered by the trustees two months before. Nothing further was heard of by-passing the village, and the railroad, in token of peace, promised to build a new depot and repair all cattle guards.

When the road first opened in 1867, all the offices and shops were located in Jamaica. Since the road owned very little rolling stock and land at first, these facilities were poor and limited; one flimsy engine house blew down in a winter storm in December 1867. Just as soon as the decision was made to fix the Brooklyn terminus at Bushwick, all the administrative offices were transferred there on August 5, 1868, and the engine and machine shops soon followed.

The problem of handling freight inspired the construction of a dock facility on Newtown Creek. The Brooklyn terminus at Bushwick was a mile from the waterfront and the single track line through crowded residential streets made freight car movements difficult; one of the most profitable viz. the handling of manure, was expressly forbidden as a health menace. In August 1868 the directors planned the spur to the new dock and in March 1869 a bill was introduced into the Legislature to permit such construction. Over the summer the single track spur was laid from the main line at about the present junction of Metropolitan & Flushing Avenues north to the dock just above where Maspeth Avenue used to intersect Newtown Creek before it was obliterated by the Navy Yard. Whether there were cranes here for loading and unloading manure barges is uncertain; however, the railroad went ahead in February 1872 with another freight dock at Hunter's Point installing $25,000 worth of facilities.

From the day the South Side RR opened in October 1867, it seems to have been well patronized and successful. Part of the reason for this prosperity was undoubtedly its newness: new engines, new cars, and a new and heavy roadbed. The South Side also had the advantage over its rival, the Long Island RR, of passing directly through old and well-established villages all along the south shore. A third attraction was its fare schedule, which generally set rates slightly below those of the Long Island RR. Between 1868 and 1872 the following fares prevailed from New York or Brooklyn:

| Fresh Pond or Glendale | 15¢ | South Oyster Bay (Massapequa) | 85¢ | |

| Richmond Hill or Jamaica | 18¢ | Amityville | 95¢ | |

| Springfield | 40¢ | Breslau (Lindenhurst) & | ||

| Valley Stream | 45¢ | Babylon | 1.10 | |

| Lynbrook | 50¢ | Bayshore | 1.20 | |

| Rockville Centre | 55¢ | Islip | 1.35 | |

| Baldwin | 60¢ | Oakdale | 1.45 | |

| Freeport | 65¢ | Sayville | 1.55 | |

| Merrick | 70¢ | Bayport | 1.60 | |

| Wantagh (Ridgewood) | 75¢ | Patchogue | 1.65 |

A glance at this table reveals that where the South Side was in competition with the Long Island RR between New York and Jamaica, the fares were very low (18¢) but east of Jamaica the rates rose sharply and then leveled off. In February 1869 the South Side offered the residents of Jamaica single tickets for only 15¢ or a book of 100 for $12. When Charlick found his rival getting all the traffic, he cut his rates to the same figure, then fearful of a war, arranged a meeting with Fox, resulting in a non-raiding agreement. Within a week the fare rose to its old level of 18¢ to the disgruntlement of the Jamaica citizenry.