RAHWAY VALLEY RAILROAD HISTORY

New York and New Orange Railroad 1897-1901

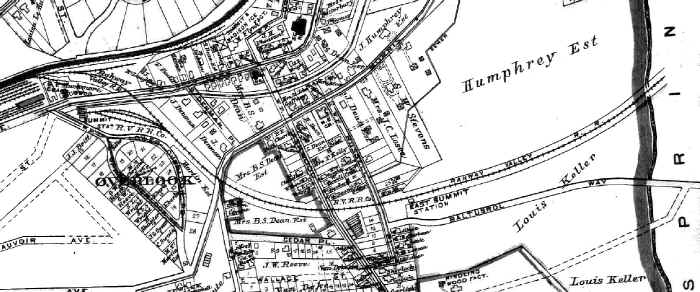

From 1897 until 1901 the New York and New Orange Railroad operated

four miles of track including the Lehigh Valley and Jersey Central

interchanges to the end of what was later known as the Monsanto Branch. The

railroad was chartered in June, 1897 by members of the New Orange Industrial

Association to serve their factories in New Orange (Kenilworth.) In the

charter for the railroad the line was given permission to build to

Summit, but limited funds prevented this. For the year 1899 the

factories in New Orange were shut down, due to an economic recession. The

NY&NO only operated passenger trains for this year. The 4-mile NY&NO

soon became unprofitable and soon stopped paying taxes and was sold under

foreclosure in 1901 to the recently organized New Orange Four Junction

Railroad.

New Orange Four Junction Railroad 1901-1905

This short lived railroad was organized by William W. Cole and

several partners to take over the foreclosed on New York and New Orange

Railroad. During it's entire four years of operation it was mostly a

break-even deal for this railroad. In 1903 the NOFJ was contracted by the

Pennsylvania Railroad to remove the soil from Tin Kettle Hill for the PRR's

approach to it's New York City tunnel. The PRR became very interested in

this line and helped it to acquire right-of-way to build a line to Summit.

The PRR also had plans to extend the railroad south to it's line. Surveys

for the line to Summit were made in 1902. Due to financial problems in the

company the NOFJ never extended to Summit. William W. Cole was strongly

against selling the NOFJ but finally sold the struggling company to the

Rahway Valley Railroad on March 1, 1905.

Cross Country Railroad, Project of the Cross Steam and Electric

Railway Company 1903-1904

In 1903 the Cross Steam and Electric Railway Company started a

project called the "Cross Country Railroad". The CS&E Ry. acquired

the right-of-way in Summit to eventually build a rail line to the NOFJ

in New Orange. Surveys were made and a branch was planned to Millburn. The

CS&E Ry. was going to start construction in early 1904 of the line, but

contracts were not allowed, Louis Keller actually signed a petition to allow

the rail line. The CS&E Ry. gave up on the project in April of 1904 and

rather started work on a trolley line in Summit instead. Louis Keller soon

took matters into his own hands with the charter of the Rahway Valley

Railroad on July 18, 1904.

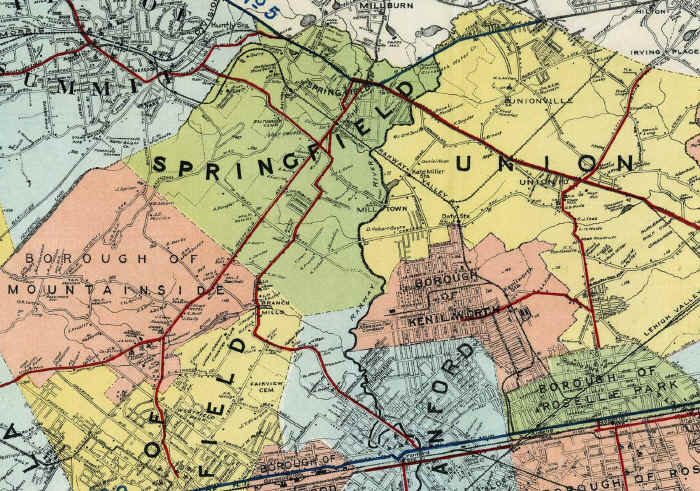

Rahway Valley Railroad Company 1904-1986

On July 18, 1904, Louis Keller, and several associates, some of

which were formally of the New York and New Orange Railroad, chartered the

Rahway Valley Railroad to run from New Orange where a connection would be

made with the NOFJ, to Summit, where a connection would be made to the

Lackawanna. The NOFJ was purchased by the company on March 1, 1905. In 1909,

to lower costs, Keller created a lessee company, the Rahway Valley Company,

to lease the entire railroad to, to lower costs. The Lessee company was

controlled by the Keller family for it's entire existence. The Rahway Valley

Railroad Company, owned all of the track, stations, and other structures,

from Roselle Park to Summit, and the Monsanto Branch, but was operations and

equipment were carried out by the lessee. When the line was purchased

by the Delaware Otsego Corporation it was consolidated with the Rahway

Valley Railroad, Lessee and Rahway Valley Line into the Rahway Valley

Railroad Company, a subsidiary of the Delaware Otsego Corporation.

Rahway Valley Company (Lessee Corporation) 1909-1986

In 1909 Keller organized the Rahway Valley Company to

lease the railroad, to operate the railroad, and furnish it with

locomotives. It was commonly referred to as the lessee. Once organized,

close friend of Keller, Charles J. Wittinberg was made president of the

lessee. He served in that capacity until March 19, 1919 when he died in

office. R.H. England served as president from 1919 until he quit

in 1920. Then the Clarks oversaw the operation of the lessee until the

last Clark's death in 1975, and then Bernard Cahill took over as president

of the lessee until the entire operation was sold in 1986. When the line was

purchased by the Delaware Otsego Corporation it was consolidated with the

Rahway Valley Railroad Company and Rahway Valley Line into the Rahway

Valley Railroad Company, a subsidiary of the Delaware Otsego Corporation.

Keller and his family controlled the lessee for it's entire existence.

Rahway Valley Line 1911-1986

In 1911 Keller created the Rahway Valley Line to build a

three mile branch to Maplewood. The Rahway Valley Line was controlled by the

Keller's and owned the entire line to Maplewood. When the line was purchased

by the Delaware Otsego Corporation it was consolidated with the Rahway

Valley Railroad, Lessee and Rahway Valley Railroad Company into the

Rahway Valley Railroad Company, a subsidiary of the Delaware Otsego

Corporation.

Rahway Valley Railroad Company 1986-Present

When the entire operation was sold to the Delaware Otsego

Corporation in 1986 the three companies were consolidated to form the Rahway

Valley Railroad Company, which was made a subsidiary of the DO. The offices

of the company were moved to Cooperstown and the company was put to use in

leasing railroad equipment and property. Presently the Rahway Valley

Railroad Company employs five people, it's offices are at 1 Railroad Avenue,

Cooperstown, NY and it's phone number is (607) 547-2555.

Research: Richard King 2009

Charles J. Wittenberg 1909-1919

R. H. England 1919-1920

Roger A. Clark 1920-1932

George Arthur Clark 1932-1969

Robert George Clark 1969-1975

Bernard J. Cahill 1975-1986

Vice Presidents

Edward G. Thompson 1909-1916

E.L McKeirgan 1916-1926

Paul Donovan 1926-1961

Louis Weeks, Jr. 1961-1978

William Brennan 1978-1986

Secretaries

Haratio Franklyn Dankel 1909-1914

J. S. Caldwell 1914-1922

Roger A. Clark 1920-1932

George Arthur Clark 1932-1969

Robert George Clark 1969-1975

Bernard J. Cahill 1975-1986

General Manager

Haratio Franklyn Dankel 1909-1914

J. S. Caldwell 1914-1922

Roger A. Clark 1920-1932

George Arthur Clark 1932-1969

Robert George Clark 1969-1975

Bernard J. Cahill 1975-1986

Treasurer

James S. Gilbert 1909-1935

Paul Donovan 1935-1961

Margaret P. Rosebault 1961-1975

Henry Waffle Jr. 1975-1986

In the 1880s and early 1890s, Charles W. Manahan Jr. of East Orange, NJ was managing projects of building commuter towns in New Jersey for businessmen and their families to live in, out of the hustle and bustle of the big city. What towns he helped to build, we may never know, but in 1894 he embarked on another similar project.

Manahan, who was originally from Elmira, NY, came up with an idea for another commuter town. Manahan got the support of several associates from Elmira for the project. In early 1894, he traveled to Elmira to meet with his supporters. Among those present at this meeting in Elmira were, Robert Grimes, Charles M. Tompkins, William W. Cole, E.J. Dunn, and W.S. McCord. They formed the New Orange Industrial Association (NOIA), the name stemming from where Manahan had been living in East Orange.

The NOIA raised it’s money mainly from Elmira investors and settled on where to build, a flat area in the southwest part of Union Twp, NJ near the Rahway River, in the shadow of Tin Kettle Hill. They hired J. Wallace Higgins to create a master plan for New Orange, and the plans called for, five factories, many homes, trolley lines, a lake to be named Lake Wewanna, a city hall, and a railroad. A railroad would be needed to serve the town and factories to be built in the town, on Higgins’ original plans it was titled the “Belt Line Railroad.”

The NOIA decided it was time to build the railroad. On June 9, 1897, the New York and New Orange Railroad was chartered, with $100,000 startup capital. Robert Grimes was elected president, Dennis Long of Union became vice president, W.S. McCord became Treasurer, and Charles W. Manahan Jr. became Secretary. The board of directors consisted of these four along with Theodore C. English and Nicholas C.J. English of Elizabeth, and George B. Frost of Newark.

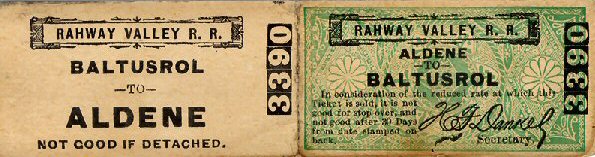

The original charter of the NY&NO provided for about eight miles of track, a mainline from the Roselle Park section known as Aldene to the city of Summit, a branch to the Lehigh Valley, and a branch to a NOIA factory on the Rahway River.

Surveys were made in June and July of 1897 by Higgins and assistant, Anthony Grippo. They decided on a curvy route, that would start at Aldene on the CNJ, run north, turn slightly left, continue north, turn ninety degrees to the right, and then ninety degrees to the left, and temporarily terminate in New Orange before funds could b e raised for the extension to Summit.

Locals were hired and through late-1897 and early-1898 the line was built two miles from Aldene to New Orange. A CNJ locomotive was leased along with several flatcars for construction. Rail was decided to be 60 lbs. to the yard.

By summer 1898 the line was completed to about 50 yards past a road known only as “Boulevard.” A station was constructed near that road, and in July, 1898 the NY&NO purchased three locomotives for service from the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR), all of the 4-4-0 American type, wheel arrangement. Nos.2 and 3 arrived that year while No.1 was overhauled by the PRR, and it arrived in early 1899 on a CNJ freight train. Passenger coaches were acquired secondhand from the CNJ and immediately put into service. A roundhouse was constructed for the purpose of housing and maintaining the locomotives and equipment as well.

The excitement of 1897 and 1898 was met by the doom and gloom of 1899. With 1899 came an industrial recession and the factories in New Orange shut down for the year, and remained closed until early 1900. The NY&NO deferred paying taxes and the NOIA sank into debt. To try to gain more business the connection to the Lehigh Valley Railroad was forged in 1899 with the building of the half-mile long, Lehigh Valley Branch, along with the construction of the Warren St. Station, but these resulted in little success,20and the line sank farther into debt.

NOIA president, Charles M. Tomkins died in late-June, 1900 at age of 47 of appendicitis, and not much later, on November 8, 1900 the NY&NO was foreclosed on after not paying back taxes for about a year. One NOIA associate, William W. Cole, became greatly concerned, and knew that if the railroad failed, so would the town.

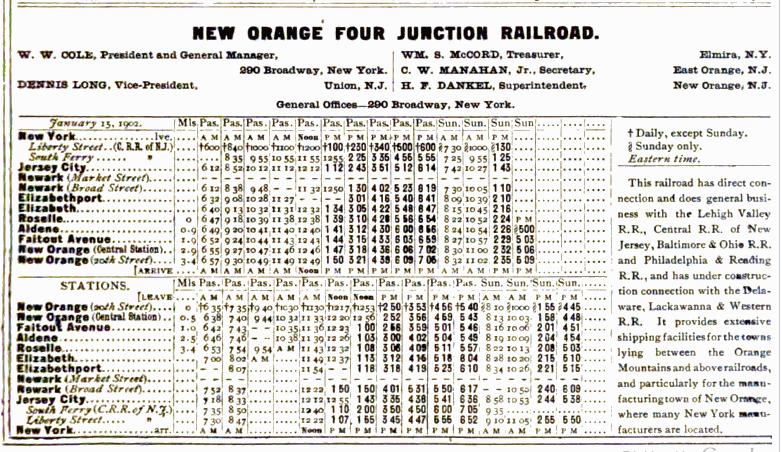

So he quickly organized the New Orange Four Junction Railroad on February 4, 1901 along with the help of W.S. McCord, H.H. Hollock, and George B. Frost. Several days later on February 16, 1901 the NOFJ purchased the New York and New Orange Railroad at a sheriff’s auction held at the Union County Courthouse in Elizabeth.

In 1902, the NOFJ had a debt standing at $83,497.35 and during that year it had only made $2,997.92 Cole had several sidings built and the line reached a length of 3.97 miles in 1902. At this rate if all earnings had gone to pay off the debts, it would of taken almost 28 years to do so.

New Orange Four Junction Railroad Timetable January 15, 1902

Cole was looking for his railroad’s

niche, it’s money maker, and that did come with the beginning of 1903.

The railroad which asserted itself as the “Standard Railroad of the

World,” the Pennsylvania Railroad was building a tunnel under the

Hudson River to New York City, but a four mile stretch or marshland

stood in the way, and a large amount of fill would be needed. Cole heard

that the PRR was looking for fill, and pointed at the 186-foot Tin

Kettle Hill.

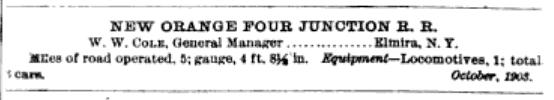

NOFJ official railway equipment listing from October, 1903

The PRR purchased Tin Kettle Hill among other places along the NOFJ only for the purpose of their soil. Two large steam shovels were acquired, and the NOFJ locomotive worked overtime hauling carloads of fill, along with keeping up with the NOFJ schedule of 14 passenger trains a day.

Cole was so ecstatic about this, that he went as far to say that right-of-way to Summit had been acquired, and that the line was going to be extended to Summit and be purchased by the Pennsylvania Railroad, in reality none of this had ever happened. Although earnings had jumped by over $12,000, in 1905 debt had mounted to about $100,000, and no money had ever been allocated to extend the line.

Meanwhile, in 1895, publisher of the “Social Register,” a book of all the elite socialites, had founded the Baltusrol Golf Club in Springfield, NJ, a town that was to be along the NY&NO, if it had ever been built. From 1897 to 1904, Keller had waited and waited for a railroad to come to his golf club, so his friends could travel in comfort. He became part of several schemes to extend the line from New Orange, but none ever materialized, after the most recent one, the Cross Country Railroad, was dropped by the parent company, Keller took things into his own hands.

He attracted former NY&NO and NOIA associates and members, NOFJ investors, and his own friends and associates to his project, and before he knew it on July 18, 1904, the Rahway Valley Railroad was chartered, to run from New Orange to Summit. The first board of directors were, Louis Keller, W. Irving Scott, Nicholas C. J. English, George B. Frost, Charles W. Webb, and Edward G. Thompson. English and Frost were formerly board members of the NY&NO and were current members of the board of the NOFJ.

Mr. Higgins was hired on again to survey a route for the line from New Orange to Summit. He chose a route to travel north, cross Chester Road (now Rt.22), head northwest to cross Springfield Road (now Liberty Ave) near the Elfein House, continue through marshy ground and cross the Rahway River, it would continue northwest to cross Mountain Ave in Springfield, and continue in a strait line to within several hundred yards of the Baltusrol Golf Club, then it would turn north a begin a stiff 4% grade uphill. A horseshoe curve would create a more gradual grade then if it was in a strait line. It would cross Orchard Street and Shunpike Road before crossing into Summit and turning ninety degrees to turn northwest again. It would cross over Russell Place, Ashwood Avenue, Morris Avenue, and Broad Street before connecting to the Delaware Lackawanna and Western Railroad in Summit.

Construction started that year and an old 2-6-0 Mogul was purchased from the DL&W to assist in construction. Construction was slow paced and only went in to the early winter months of late-1904. In early 1905, Keller entered negotiations with William W. Cole about the RV and NOFJ consolidating. Negotiations dragged on for several weeks, and on March 1, 1905 the New Orange Four Junction Railroad and Rahway Valley Railroad were consolidated, keeping the name of the latter road. Cole was made president of the line after the consolidation.

The DL&W mogul was numbered 4 in the numbering arrangement of the NY&NO and NOFJ, and No.3 joined the RV fleet. It soon became apparent the with construction, passenger trains, freight trains, and the still ongoing removal of Tin Kettle Hill, the two locomotives would not be adequate. So Keller had two more locomotives purchased, one was an 0-6-0T purchased from the CNJ and numbered five, and another was from the Baltimore and Ohio owned, Staten Island Rapid Transit Line (SIRT) and was a 2-4-4 and numbered six.

With two more locomotives purchased in 1905 work continued on construction. Construction pushed into May when the line reached Springfield on Mountain Ave. On May 24, 1905 the line was formally opened to the public with a ceremony. Then secretary of the road, and primary owner, Louis Keller rode a special passenger car decked with flowers and wreaths pulled by an RV hog into Springfield, amid much fanfare. It was the first and only railroad to enter the town’s borders.

Construction would of reached the town much

earlier if it hadn’t been for the marshlands around the Rahway River.

Large amounts of fill had sank into the ground, and had to be redone,

correctly. Solid bedrock had to be located for the bridge, and

construction here set back the construction a couple of months.

After the excitement of May, construction began toward the Baltusrol Golf Club. Never deviating from its straight line, the line passed within a few hundred yards of the club. It was at this time that construction of two stations was begun, one at Springfield and another at Baltusrol. Local Union farmers, Mr. A. Miller and Mr. John Doty persuaded Keller to build two small stations near their farms. Arion Station, commonly known as “Kate Miller Station” was constructed on Springfield Road and Doty Station was constructed on Chester Road.

The stiff grade to Summit was begun in June, and much grading was done and by September the line had started constructing it’s Russell Place bridge, over that road, and by early October it was completed. The city of Summit had a certain policy of having permission of from the city to build anything within their town, and Keller who was a resident of Summit, dimwittedly forgot about this, and on the night of October 5, 1905, with the use of a steam roller, the city of Summit tore down the bridge and brought it to an empty lot nearby for the railroad to find it.

Luckily the engineer spotted it on the next day’s work train otherwise disaster would of occurred. The RV scrapped the almost brand new bridge and built another with proper permission. Construction pressed into the early months of 1906 with the construction of the Ashwood Ave, Morris Ave, and Broad Street bridges. When the line bridged Broad Street it asked permission from the DL&W to connect to it’s Morris & Essex line, and it was denied.

The line instead built a station at 270 Broad Street and a small yard complete with a water tank and coal bin for refueling after the long grade and strain on the locomotives. After the completion of the line to Summit in 1906, and what is seemingly a RV tradition, it was met with some disaster.

That year No.3 was wrecked after traveling at a high rated speed near the Rahway River trestle. Another accident resulted when a passenger train got loose from the locomotive going up the Summit grade and plowed into a locomotive in Springfield.

Cole stepped down from the presidency of the line in 1907 and moved back to Elmira, NY, he remained a stockholder until his death in 1915. Keller assumed the presidency of the line that year. Cole had managed to get the line extended to Summit and on a somewhat profitable track.

A schedule was established to allow for fourteen passenger trains a day, roundtrip. RV locomotives had trouble hauling the four and five car varnish up the mountain to Summit. The train was often doubled between Baltusrol and Summit, meaning half the train would be brought up the mountain and then the locomotive would run light to fetch the other half and bring it up the mountain, this was the only option as doubleheaders and pusher locomotives were unheard of on this line. This power crisis was resolved with the purchase of locomotive brand new locomotive No.7 in 1908 from the Baldwin Locomotive Works.

While No.7 was a big hit, the RV still owned three old, “teakettle” locomotives, Nos. 4-6, and they were maintained by an old ancient, ineffective, roundhouse near the Warren St. Station.

On June 24, 1908, Keller brought his case to court regarding the Summit connection to the DL&W. The courts ruled in his favor, but on August 25th the DL&W sought to suspend the approval by Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC). The ICC fought on the side of the RV and the court battle was brought to Washington, D.C. On October 22, 1908, U.S. circuit court Judge Lacombe ruled in favor of the DL&W and overruled the approval by the ICC, it would be another twenty one years before the case would be opened again.

By 1909 passenger trains had dwindled from fourteen a day to just six. Freight service was light, the factories in New Orange built by the NOIA had closed, the NOIA went bust, and the land was sold and became Kenilworth in 1907. To try to cope with mounting losses, Keller allowed outside interests in and on February 27, 1909 he created the Rahway Valley Company (RVC) to lease the line for five years, for $6,000 for the first twelve months. Close New York associate of Keller, Charles J. Wittenberg was made RVC president and put on the RV board of directors. Wittenberg signed his name on the five year lease on March 1, 1909.

This gave the railroad a new “lease” on life, but it actually did little good. Investors pointed toward Maplewood’s Hilton section for another source of income. Keller created the Rahway Valley Line in 1911, it is of note that the RVL was not a corporation, but rather an organization, and Keller owned all of it. The RVL laid out a line from near Doty Station northeast in a mostly strait line to a section of Maplewood known as both Hilton and Newark Heights. The RVL three mile line was only ever adorned by one station, Unionbury Station, and in Newark Heights there was only ever a freight office.

In was at this time, 1911, that Keller invested a little money into two gasoline rail buses, numbered ten and eleven. Ten was bought new from a company in Philadelphia and Eleven was bought from Mack. Small turntables were constructed for=2 0them at Baltusrol, Kenilworth, and in Maplewood. A small roundhouse was constructed for them in Kenilworth. They paid well for awhile and the passenger car fleet was cut back to just three coaches, making runs between the rail buses.

The companies dragged through 1912 and 1913, not knowing where the next penny was coming from. In 1914, a Millburn trucker won the RV mail contract, and rail bus ten was scrapped, and eleven was retired for a pending future.

That year the lease between the RV and the RVC was renewed and Louis Keller sat and waited for overwhelming business. Then it happened! War broke out in Europe, the war to end all wars, World War I. WWI proved very profitable for the rail lines of the nation. Factories became busy with the demands from overseas and new factories were being built up and down the coast to serve their needs.

The U.S. adopted a policy of “cash and carry” in the sale of munitions to belligerent nations overseas. Two munitions plants opened up on the line in 1914 and the line started to become more active. A gunpowder plant was built by the American Can Co. in 1914 on the Rahway River Branch. On the RVL also known as the “Unionbury Branch” a plant only known as the “Fireworks Factory” was opened by Czarist Russia and shipped via the RV.

A disaster on the Unionbury Branch almost destroyed the Fireworks Factory, and rumors of German spies caused the line to hire armed guards to protect the rails from foreign infiltrators.

The American Can Co. provided a string of eight coaches that came from Staten Island via the SIRT every morning loaded with passengers and then transferred to the RV. The Lehigh Valley ran it’s trains up to Kenilworth for a time to bring in workers, and the CNJ shipped as many as 5,000 arsenal workers a day for three shifts.

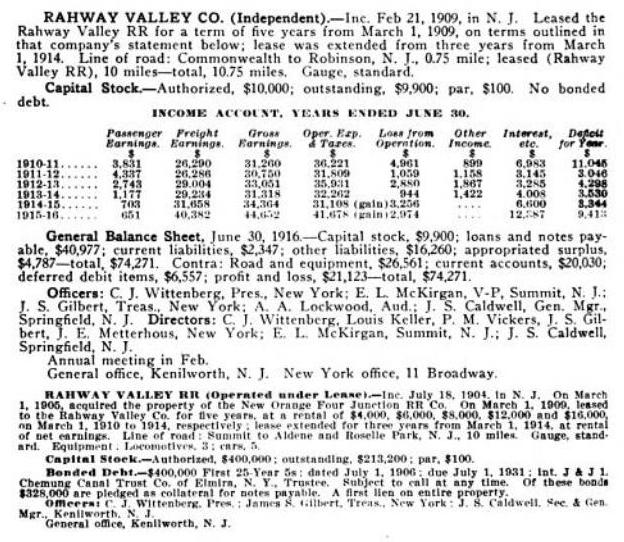

RVRR listing in Poor's and Moody's Manual from 1916

In April, 1917, the U.S. entered the war and freight traffic on the railroad became busier than ever before. The strain put upon the railroad’s three leaky, tea kettle locomotives, four through six were great, so power was leased from the LV, and CNJ, and the PRR, the latter road providing it’s own crews. Around the clock the RV was moving some piece of freight somewhere.

But just as Keller was about to pat himself on the back for sticking with the railroad for so long, and not doing away with himself, the armistice was signed on November 11, 1918, and it was all over virtually overnight. Leased locomotives were returned to their rightful owners, the Can Co. dumped it’s passenger coach fleet, and the RV was back to where it was in 1914.

No.8 was purchased in 1916 to help with freight movements, and Nos. 6 and 7 were sold, and shipped to Spain to help with the war ef fort. Nos. 9 and 10 were acquired in their place. At the end of the war old leaky No.4 was finally scrapped after a 48 year existence. No.5 was put on the passenger train jobs, which were most of the time now, only one coach long.

Then in Spring, 1919, Keller dumped two of the three coaches the line had, and retained one combine coach and refurbished rail bus eleven and put it into service mainly carrying workers.

The passenger stations were closed, Baltusrol Depot was leased out, Kenilworth Station was turned into the company offices and the railroads maintenance facilities were moved there from the old and ancient worn out roundhouse on the Rahway River Branch. Springfield Station was converted into a freight office, Summit Station was semi-abandoned, Unionbury Station was converted to a freight house, Warren St. Station was torn down, and Arion and Doty Stations weathered a few neglectful years before being torn down in the mid twenties.

On March 19, 1919, longtime RVC president, Charles J. Wittenberg died at his home in New York City. Keller hired on local R.H. England that year to manage the RVC as president. Also that year Keller possibly made the best decision of his life. It is not clear whether Keller brought them east, or if they came on their own, but in 1919 Keller hired Rochester native, 49 year old, Roger Arthur Clark as auditor of the line. His son George Clark was put on as a brakeman.

Mr. England did not take a liking to Mr. Keller’s business tactics. England quit as president in 1920, and no one clamored for his job of fixing this streak of rust. Everyone pointed at the recently hired Roger Clark for the position of RVC president, and Clark was made president. After the deaths of several of board members of the RVC and on the RV, several lawyers became board members and with Clark guiding them they started working toward getting the line out of it’s pool of red ink.

One obstacle facing Clark, was Keller, who was now in the last years of his life. He controlled the voting stock and the board. The voted to keep the rail bus and mixed trains in service, and he had his way, to Clark’s dismay.

Clark started his regime with the purchase of a 2-6-0 Mogul from the Grafton and Upton Railroad in Massachusetts and it became No.11. The little switchers, nine and ten, were retired, and Nos. 8 and 11 handled all business.

Roger Clark rekindled business ties with former customers of the railroad, and things gradually started to pick up on the line. Clark siphoned revenue from anywhere he could find it. One was from silent movies made using the railroad’s equipment, but when an employee of the movie company was mixing some camera dope in a shack adjacent to the Kenilworth Depot, the dope spontaneously ignited and blew out every window of the old station, that was carrying it too far. Fox Films was the last to make a film on the railroad.

Keller died on February 16, 1922, and Clark finally discontinued all further passenger business on the line. The combine coach and rail bus were scrapped. Keller’s holdings were put into an estate and his nephew, Charles Keller Beekman became the executor and controlled the voting stock.

Probably the only blunder that Clark made during this time was the purchase of former Bessemer and Lake Erie consolidation No.12 in 1927. No.12 was much to big on the line and saw little use, and was retired in 1929.

Clark guided the RV to steadily become a money maker, and ironically as the country sank into the Great Depression in 1929, that is when the RV began to make more money. Roger Clark entered negotiations with the DL&W, which was suffering from the effects of the depression, about the old connection at Summit. And in April, Clark scrapped old No.8 along with two 2-4-0s of an excavating company the owed Clark money and reinvested the money from the scrap into two Lehigh and New England consolidations, and they became Nos. 13 and 14. Better times were ahead indeed!

Perhaps the greatest achievement ever made by Roger Clark in his railroading career was the connection of the Rahway Valley Railroad and the Delaware Lackawanna and Western Railroad in 1931, after=2 0many, many years of failed attempts. The RV was now a bridge line, and steadily began to make more money.

Sadly Roger Clark would not live to see the line make a true net profit. Roger Arthur Clark died in his home in Union after a long illness on October 3, 1932 at the age of 62. Beekman pointed toward Clark’s only son, George, to become the president of the RVC, again no one else wanted the demanding job of RVC president.

George Clark became the president of the RVC at the age of 31, and would hold the position until his own death. George Clark guided the line to make it’s first true net profit in 1934, something it had not done since 1917. With the extra money, Clark invested in a twenty year old Lackawanna caboose, and numbered it 102, consecutive with a flat car the railroad owned years back numbered 101.

The American Laundry and Machine Co. moved into the former Can Co. property and provided a good source of income for the railroad. The railroad was on it’s way to better fortunes. The nation was healing from the Depression, boom times were ahead.

Business picked up greatly and Clark found it necessary for another locomotive to replace oversized No.12, and worn out No.11 in 1937. Master Mechanic, Carl Nees, was sent to Oneida, TN to look over a locomotive there, and he returned home with a new steamer for the railroad, No.15, the last one it would ever purchase. With it’s arrival No.11 was scrapped.

With the beginning of our nation’s involvement in World War II in 1942, factories began to again locate themselves on the Rahway Valley Railroad. No where near the boom of the first world war, the second war provided extra money, but it was not what kept it in the black as was with the first war.

In 1942 the line took in a $27,000 profit after the bills were paid. 1943 brought the line a net profit of $20,000, some of that coming from the money the railroad made when it scrapped No.12 that year.

It was during this time that trucks began to take away the railroad’s business. It started losing some customers, and some business of others, but Clark persevered.

With its three steam locomotives the Rahway Valley continued to make money all through the 1940s. The railroad made $307,729 in 1946 and had a net profit of $70,863. This was the Rahway Valley's biggest year. Trucks had started to chip away at the Rahway Valley's profits during the 1940s as the companies along its route were switching over to truck freight.

The Rahway Valley made $208,195 in 1949 and had a net profit of $20,947. It was becoming evident that the Rahway Valley was being challenged by truck freight. Most of the steel business that the line had enjoyed for years20was gone by 1950 and also by 1950 the Rahway Valley was carrying 90% inbound and 10% outbound as outbound was now mostly being handled by trucks.

Then Clark with a sigh invested $100,000 in a new diesel locomotive at the end of 1950. The general electric 70 ton, 600 horsepower locomotive arrived on January 29, 1951 freshly painted in red and yellow, and adorned with Rahway Valley lettering and the number 16. No.14 was retired and scrapped in December, 1951. Nos. 13 and 15 were kept in service awhile longer.

Clark invested into a new three stall engine shed in 1950 and the old dilapidated steam shops were torn down and the yard tracks reorganized. A diesel fuel tank was constructed next to the shops to serve the new locomotive.

No.13 was scrapped in 1952, after being retired at the end of 1951. No.15 was kept in service, but in late-1953 Clark announced the line was purchasing another diesel. On November 28, 1953, the RV operated No.15 for the last time. Another GE 70 ton model identical to No.16 arrived on February 2, 1954 numbered 17 in green and yellow paint. No.15 was stored in the diesel shop for further developments.

On January 13, 1959, George Clark was threatened by his track gang workers, consisting of four men, that they would strike without a raise in pay. They wanted a pay raise from $1.43 to $2.03 an hour. All four men were membe rs of the United Railroad Operators Crafts Union.

Clark responded to the New York Times about the subject “If they strike, we are prepared to go on without them.” The picketers blocked the tracks, but were inclined to step out of the way when a train came by.

It was said that Clark’s employees were afraid of him, and that especially true when Clark punched out a CNJ freight salesman clean in the face one day at the Kenilworth offices. The railroad went through brakemen like paper towels, one man hired worked for exactly two days, and was never heard of, or seen again. It is unclear whether the strikers ever came back to work or not, but judging by how stubborn Clark was it is highly unlikely.

Clark sold No.15 in May, 1959 to wealthy seafood tycoon, F. Nelson Blount and it was put into service on his Steamtown railroad until 1973. Caboose No.102 was sold off in the early 1960s after several years of little use.

The railroad’s once sizeable coal tonnage dropped off in the 1960s and the Falk Coal Company closed, and Woolley Fuel discontinued it’s use of the railroad. What suffered the most during the 1960s was the RVL into Maplewood, business here was down to two or three customers and infrequent trips across the Essex county line.

On other parts of the line the railroad still operated profitably. In Summit there was the Foster-Bell Plant, and the Erie-Lackawanna connection (formerly DL&W). In Springfield there was the team track and Schaible Oil, in Union there was Elastic Stop Nut, Western Electric, among others. Kenilworth had the huge Monsanto Corporation located on the Rahway River Branch, a pharmaceutical plant, Volco brass, and many more. And in Roselle Park there was the Lehigh Valley and CNJ connections.

On April 8, 1969, the longtime RVC president and employee since 1919, died in the Kenilworth Station after being with the road for fifty years, and almost never missing a day of work. His son Robert George Clark succeeded him to the presidency.

Robert, only known as Bob, tried to keep his grandfather’s and father’s streak of rust alive. Customers were disappearing and weeds began to creep over the tracks. A big help to Clark happened in the early 1970s with the coming of CNJ freight salesman, Frank Reilly. He worked closely with industry along the line to bring more of their truck shipped freight onto the RV. For awhile it proved successful, and brought in some much needed revenue.

The line into Maplewood closed in 1973 after the ICC approved it’s abandonment. Only one customer, Maplewood Building Specialties remained on the once busy line in Essex County, and it only shipped occasionally via the RV. The line was torn up from near Vauxhall Road to Maplewood, no customers remained on this segment any longer.

After trying to get rid of some insect infestation, on August 22, 1974, the Rahway Valley Railroad’s landmark Kenilworth Station was severely damaged in a fire that almost completely destroyed the interior. Valuable files were lost forever, and above all the RV lost it’s office space.

Management worked out of a work site trailer for the remainder of Bob Clark’s regime as president of the road, until his untimely death in 1975. When Bob Clark died in 1975, it was the end of the end of the fifty-six years that the Clark Family had been with the Rahway Valley, it was definitely the end of an era. The 1970s also marked the tearing down of the RV stations at Baltusrol and in Summit.

Veteran railroader, Bernard J. Cahill, was hired on as president of the Rahway Valley Railroad in 1975 after the death of Clark. Cahill wanted to give a much needed overhaul to the railroad’s image as well as improve it physically and financially.

Cahill received federal funding to upgrade tracks in Kenilworth and in Roselle Park. Old 70 lbs. rail was upgraded to new 100 lbs. rails. The interchange with the Lehigh Valley was upgraded and a small yard was constructed here for interchange traffic.

Seeing the Kenilworth Station was beyond repair, and the office trailer was not cutti ng it, in 1976 Cahill acquired a former LV club car and converted it to house the railroad’s offices. He made the purchase for $3,500. A boxcar served as the railroad’s makeshift vault housing company records. Cahill also improved the railroad’s image by repainting Nos. 16 and 17 into identical maroon and white paint schemes.

With all this improvement, came a major blow, a longtime RV tradition. On April 1, 1976 the U.S. government combined several northeast railroads, including the LV, CNJ and the EL, the RV ‘s three interchange partners. Accompanied by the closure of Foster-Bell, the RV line into Summit was closed and the line only operated to just past Springfield Station.

In 1979, Cahill bought the line it’s first pieces of rolling stock since the purchase of Caboose No.102 in 1934. He purchased twenty-four boxcars new for interchange traffic, in three different paint schemes, maroon, orange, and in red. The RV boxcars could be seen traveling in freight trains all across the country. 1979 also marked the tearing down of the 81 year old Kenilworth Station, which was devastated by fire several years prior. A RV diesel assisted in the crude dismantling of the structure, and had a hard time doing so, as the structure was so sturdy.

In 1980, the Baltusrol Golf Club hosted the U.S. Open. In conjunction with the United Counties Trust Company, the Rahway Valley ran a special passenger from June 9th to June 15th. Passenger coaches were leased from the Delaware Otsego Corporation.

Trains were operated in a push-pull arrangement with either Nos.16 or 17 at the front and the other at the rear. The train was very well photographed. From a reliable source it was reported that when passenger train ran over the Rahway River Trestle on the Union/Springfield border, the trestle bent a great deal, by almost a foot from the extremely heavy passenger coaches. A Rahway Valley boxcar with a generator was put in the middle of the train so meals and entertainment could be provided on the train ride. This was the last train to operate past the Rahway River bridge, and last train to ever turn a wheel in the town of Springfield.

By the early 1980s most business on the line was seasonal, and only a handful of customers remained on the once busy line.

In 1986, the Rahway Valley Railroad announced it would not be able to purchase liability insurance for the coming year. Keller’s Estate put the line up for sale and the Delaware Otsego Corporation purchased the line, including all three companies, on December 22, 1986.

Cahill was ousted out of the railroad all together along with other management, and some employees ended up working for the DO. The RV boxcars were sold off to various railroads, and the office car was moved to Cooperstown, NY.

The DO did little to revitalize this once flourishing line. Cahill’s improvements to the former LV interchange were overlooked and the main interchange was moved to the less used, and in worse shape, Aldene connection to Conrail.

The former LV interchange was closed forever and the Lehigh Valley Branch was torn up. Track maintenance was infrequent, and unused sidings were torn up. Derailments were frequent, and one kept a train tied up for almost three days.

Customers became annoyed by the horrible service provided on the former RV by the DO, and ended up moving away or changing to truck freight shipping.

In 1989, Nos. 16 and 17 were removed from the line and moved to other spots on the DO system and performed various odd jobs before being donated to the United Railway Historical Society in 1995.

With the year 1990 came two major blows to the dying railroad. The main customer, Monsanto Corporation closed it’s doors in Kenilworth, and the Rahway River Branch was torn up. The second, was Jaeger Lumber ending it’s use of the line, and this closed the former RVL, now known as the Jaeger Industrial Branch.

The DO allowed someone to lease track space in Kenilworth to work on a pair of former NJDOT E-8s in their years on the railroad, and the Kenilworth yards we re anything from ideal. Roger, George, and Robert must have rolled in their grave several times during the years of the DO on the RV.

The last train carried two hoppers out of Kenilworth on April 21, 1992 being powered by NYS&W No.120. This also marked the end of the SIRT line acquired by the DO in 1985.

The line was closed. The DO retained ownership of the land until 1994 when they sold it to the New Jersey Department of Transportation for future planning. Since the closure of the line in 1992, a few reminders of the old RV have been lost to time. The bridges in Summit over Morris Ave. and over Broad Street have been removed. The Shunpike Road bridge in Springfield has been removed as well. The frieght house in Springfield was torn down in 1996 after the property there was sold for commercial purposes. In Kenilworth the shops have been torn down and a strip mall has been put in it’s place. And most recently in Union, the Morris Ave. bridge which had stood since 1915, was torn down in 2007.

In 2001, the NJDOT contracted with the Morristown and Erie Railway to rebuild the line from Aldene and Summit, with the prospect of shortening freight routes and taking trucks off of the roads, but by 2006 funds for the projects had been spent, and the project not completed. As of now the project is being reviewed by the State of New Jersey, and is highly likely we will not see a train in S pringfield or Kenilworth for a long time.

Current efforts are acting to preserve the

history of the line. Alan Binenstock is working to create the Rahway

Valley Historical Society, and interested parties should contact him at RVRRHS@comcast.net.

Also there is a Rahway Valley website maintained by Steven Lynch at:

Rahway Valley Railroad

By Richard J. King © 02/2009

Louis Keller, president of the Rahway Valley Railroad Company, faced mounting losses in revenue, and increasing debts after the end of the first world war. It became obvious to Keller that passenger service was no longer profitable.

So in the Spring of 1919, Keller scrapped two of the three coaches, keeping a combine coach, closed all the passenger stations, and most passenger operations ended. Keller, who started the line in 1904 to serve his golf club, did not want to see service to his club end.

Thus, he had Railbus #11 refurbished and it was put back into service as a shuttle between Baltusrol and Aldene, for the purpose of only serving the "Blue Chip Fellows," the city folk who came out to the country for a round of golf. The combine during the week saw service at the end of the freight trains, as

a mixed train. This service was provided for factory workers only who worked in

industries along the RV. When freight was light, No.5 was steamed up to haul the lone coach, which was quite often in in those times. These

factory work and golf trains were finally discontinued after Keller's death in 1922.

By Richard J. King © 02/2009